Skin Lumps, Skin Infection, and Clubbing

IMBUS can help diagnose several skin conditions and is the definitive method for identifying clubbing, a classic Internist clue.

TECHNIQUE

Most skin lesions should be imaged with a linear probe. However, a curvilinear probe may be needed in very obese patients. The gel and probe should not come in contact with potentially disrupted epidermis. The easiest and safest way to deal with this situation is to apply an adhesive dressing (Tegaderm) and then use the gel and probe on top of this. Alternatively, a more expensive option, which isn’t always available, is a small IV solution bag (fresh out of its wrapping) placed over the lesion with the probe used on top of the bag. A water bath is excellent for smaller lesions on hands or feet, with the probe never touching the body part. However, some probes can be dipped only part-way into water. Thus, putting a large mound of gel over the lesion and placing the probe in the gel without touching the skin is an alternative. Many lesions should be examined with color/power Doppler to be sure about vascular malformations and proximity of essential vessels.

SKIN LUMPS

Patients frequently come to the clinic with recently noticed or enlarging lumps in the skin. Most of these patients are worried about malignancy. Unfortunately, even formal radiology ultrasound cannot reliably distinguish benign from malignant disease in solid skin lumps. As with lymph nodes, an essential part of IMBUS for skin lumps is accurate sizing so that a follow-up exam can determine whether a change has occurred over a short period. Yet, some lumps have an appearance that makes benign disease highly likely, which can reassure patients. Find the largest dimension of a lump and measure this as the “length” of the lesion. Then, obtain the perpendicular cross-section and measure the “width and depth” of the lesion. These dimensions may not relate to the parasagittal/transverse orientations on the body. Consistency of measurement techniques is essential amongst physicians to enable accurate follow-up exams.

Lipomas: These are the most common skin lumps and can occur anywhere. Lipomas are solid, mobile, usually elliptical lesions that grow parallel to the skin surface and have minimal or no color/power Doppler flow. Lipomas can develop slowly and become large. They rarely become malignant. They are most typically homogeneous and hyperechoic compared to adjacent muscles but isoechoic with adjacent subcutaneous fat. Perhaps most notable are the lesion's multiple, short, gently curved, echogenic lines. One dimension may show these wavy lines more prominently than another, so lumps need to be viewed in two dimensions. Lipomas should not have posterior acoustic enhancement or posterior shadowing. The following is a clip of a typical lipoma.

The following mass was clinically considered a lipoma, but the IMBUS appearance was not a good fit, and the Color was active. This turned out to be a Schwannoma.

Another clinic patient thought clinically to have a lipoma turned out to have a brachial artery aneurysm, and Color was critical to this identification.

Epidermal inclusion cysts are common and contain a jelly-like substance, a proliferation of squamous cells in the dermis or hypodermis. The term sebaceous cyst is incorrect because these do not originate in a sebaceous gland. They are firm and non-tender until they rupture, resulting in an inflammatory response with the release of necrotic debris. They are most common on the scalp, face, neck, trunk, and back. It is rare for them to undergo malignant transformation.

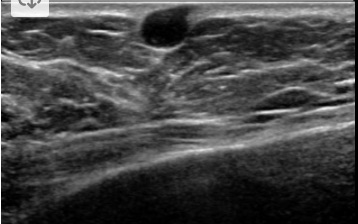

These cysts are well circumscribed and form in, or just deep, to the epidermis. It is typical to see a small neck leading to the skin surface. When small, these cysts can appear anechoic, as in the following example. A small neck can be seen with this cyst.

Larger epidermal inclusion cysts are usually hypoechoic and heterogeneous. Some posterior acoustic enhancement can be seen, as in the following example, which also has a neck.

Ganglion cysts: These are non-malignant masses near a joint space or tendon, often around the hand and wrist. Women are more commonly affected. Ganglion cysts are usually attached to a joint capsule or tendon sheath. With IMBUS, almost all are anechoic with well-defined margins unless the cyst has partially ruptured. There may be internal septations and posterior acoustic enhancement should be seen. A water bath is best to see these cysts on the dorsum of the hand/wrist, but a large mound of gel with a probe that does not touch the skin will also work. The following example shows a large ganglion cyst near the AC joint of the shoulder.

Gouty tophi: These are not common lesions, but they are a classic Internist diagnosis. Tophi can occur in the skin, on the ears, or in various soft tissues, including close to joints. The calcium in the deposits creates heterogeneous hyperechoic lumps, sometimes called “cloudy.” A hypoechoic rim has been described around the deposits. The following is a typical, smaller tophus over a first MTP joint.

The following example shows larger and multiple tophi over a wrist.

Other, more unusual causes of calcium deposits in the skin are usually denser and not very large (e.g., calcinosis and calciphylaxis).

EDEMA/CELLULITIS

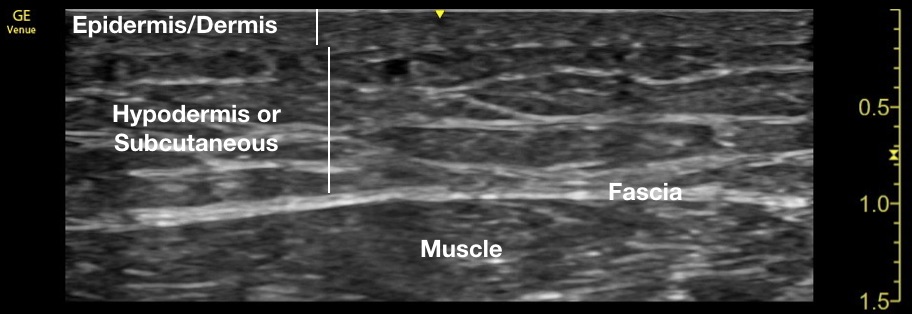

The following clip shows normal soft tissue in a leg, beginning with the superficial epidermis/dermis. The fat, nerve, and vessel containing hypodermis (subcutaneous tissue) and fascial layer follow.

The next still image shows a clinic patient with very early cellulitis. The epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis are modestly enlarged, and subtle anechoic fluid surrounds some islands of tissue. Muscle tissue is visible at the bottom.

Edema in the skin from any cause, including cellulitis, shows as anechoic fluid between islands of cells in an appearance called cobblestoning, displayed prominently in the following clip.

If a patient has cobblestoning of an arm or leg without overlying erythema or tenderness, the diagnosis of edema would usually be made. When erythema and pain accompany cobblestoning, the diagnosis would be cellulitis. However, a patient might have chronic edema from several causes, and deciding about cellulitis can be difficult. Color/power Doppler imaging is not very helpful. The only distinguishing feature noted by some experts is increased hyperechogenicity of the cell islands in cases of cellulitis, compared to simple edema. In the example just above, the patient clinically had inflammation, and some cell islands were hyperechoic.

Patients with clear-cut edema or cellulitis need to be sought during the learning phase and imaged with consistent technique and machine settings so that the visual pattern of hyperechoic tissue of cellulitis can be learned.

NECROTIZING FASCIITIS

There are several reasons to routinely perform an IMBUS exam on patients with possible or presumed cellulitis. The first is to reduce the probability of necrotizing fasciitis, a feared cellulitis requiring urgent surgical debridement and antibiotics. Necrotizing fasciitis is cellulitis plus gas in the soft tissue. Gas in the soft tissue shows as hyperechoic dots/blots, often with a dirty posterior shadow. The following clip shows a few patches of air on the left side of the screen.

This second example shows the cellulitis at the top, with a beginning phlegmon. However, the multiple dots and blots of hyperechoic air with dirty shadows are significant evidence for necrotizing fasciitis.

The sensitivity of an IMBUS exam for gas in the soft tissue is not known precisely, but ultrasound is excellent for seeing air, and the presence of air will ring an alarm bell.

ABSCESS

A second reason to do an IMBUS exam routinely for patients with cellulitis is to reduce the chance of missing an abscess. An abscess is a fluid collection, almost always complex in or below the cellulitis. The following clip shows cellulitis and pockets of abscess.

The term phlegmon is often used as fluid increases in cellulitis with some disappearance of cell islands. Determining when a phlegmon becomes a full abscess is a judgment call, but it is a practical issue because a phlegmon is rarely drained. Here is a patient with an infection on the lower leg that was phlegmon but not yet a drainable abscess.

Color/power Doppler does not help diagnose the abscess. However, it may help identify any larger vessels close to the abscess that could get infected or need to be avoided with any drainage procedure.

PANNICULITIS

There are several essential mimics of skin infection. Occasionally, acute crystal arthritis (calcium urate or calcium pyrophosphate) can suggest cellulitis because the surrounding inflammation can be intense. Specific calcification patterns in and near joint cartilage can help with this differentiation.

Acute and subacute panniculitis are other significant possibilities for patients with inflamed skin, the best-known example being erythema nodosum. The following clinic case is illustrative.

An older man had two incidents over the past two years of acute inflammatory nodules in the upper and lower anterior right thigh, both associated with mild impact trauma. Both eventually had modest drainage with slow resolution. The current episode began on the dorsum of the left foot, perhaps from footwear pressure. However, the inflammation increased after several days, during which cold packs were applied periodically to the dorsum of the foot. The dorsal foot was inflamed and suggested cellulitis. The patient had no fever or systemic symptoms, but the pain was moderately severe and neuropathic.

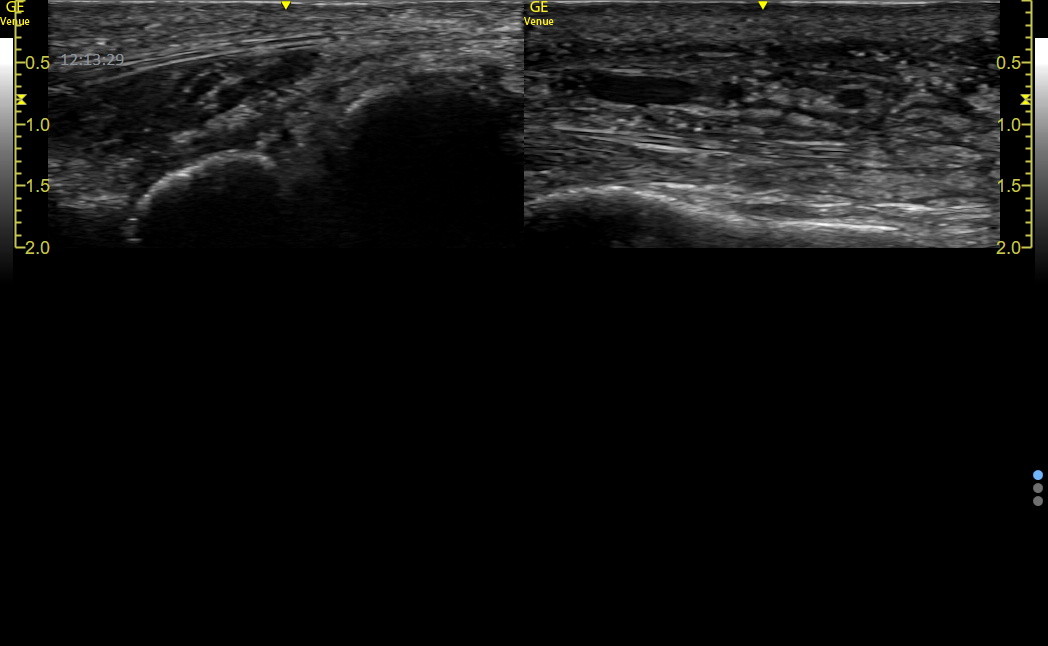

The left side of the following image shows the dorsum of the uninvolved lateral right foot with a normal epidermis/dermis/subcutaneous layer above the fascial line at a depth of 0.5 cm. Below the fascial line are muscles and then bones/joints. The comparable location over the abnormal left foot is on the right of the image. This location was over abnormal skin but not where the swelling and pain were most intense. The epidermis/dermis was distinct, but the subcutaneous tissue was thickened with increased fluid, and the fascial line was about 1 cm lower than on the normal side.

The following clip shows diffuse increased fluid in the subcutaneous layer. The epidermis and dermis are still distinct.

The fluid in the subcutaneous tissue was more loculated where the pain was most intense.

No gas shadows or deposits of calcium were identified. Blood vessels, including some dilated veins, showed excellent flow.

Dexamethasone and then celecoxib were used rather than antibiotics. As inflammation subsided, modest light brown drainage spontaneously occurred from several locations on the dorsal foot. However, a week later, a localized, intense nodular inflammation arose more proximally on the dorsal foot, having all the characteristics of erythema nodosum. The following clip shows spared epidermis/dermis with swelling and fluid collection in the subcutaneous space.

Even two weeks after the most intense inflammation of the distal foot had subsided, the subcutaneous tissue continued to show increased thickness with fluid, an example of the prolonged healing that can occur with panniculitis.

Panniculitis is poorly understood and may be misdiagnosed as cellulitis, but ultrasound can help distinguish the epidermal/dermal disruption and swelling of cellulitis from the subcutaneous pathology of panniculitis. Gas is never seen with panniculitis.

CLUBBING

Clubbing is ready to be consigned to the “ash heap of history” since the sign is rarely sought by traditional means, and few physicians think of it as an essential diagnostic clue (or know the differential diagnosis for the finding). For the few who may still care, about 1% of general internal medicine hospital patients were identified with clubbing using traditional visual methods (Vandemergel, Eur J Intern Med 2008), and about 40% of these patients had serious disease. Clubbing is a “pivot point” for diagnosis because it has a relatively restricted number of possible causes. This differential diagnosis can then be reviewed to see what might fit with a particular patient. Ultrasound is superior to visual or tactile methods for assessing clubbing.

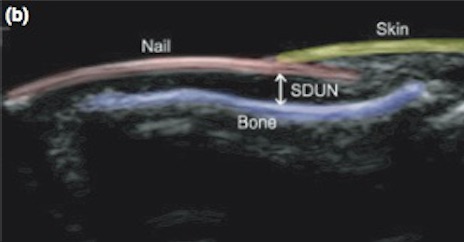

Technique: Clubbing is caused by an increased growth and softening of the soft tissue under the proximal part of a nail. The following labeled ultrasound image shows the “soft tissue depth under the nail” (SDUN), which is the key to diagnosis.

The angle between the nail and the skin, named by Lovibond, is normally ≤ 160 degrees. It is usually easy to tell when this angle has reached 180 degrees (horizontal) or greater.

The index finger is used for the exam. Images can be obtained in a water bath or with a thick mound of gel over the distal digit. Orient the probe with the indicator towards the patient’s head.

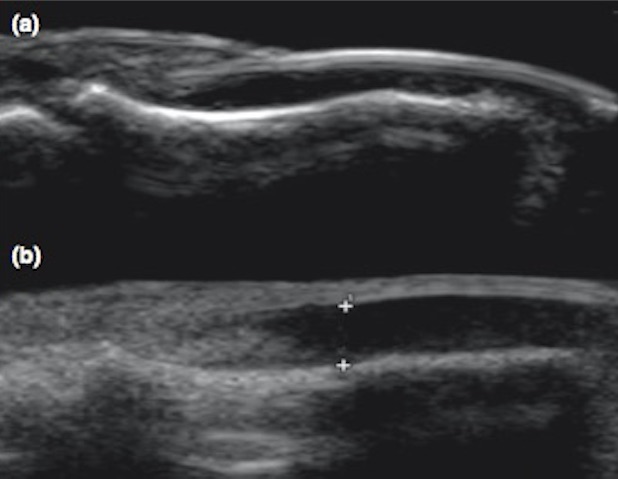

The following composite image shows a normal nail at the top and an abnormal nail at the bottom. The abnormal Lovibond angle was almost exactly 180 degrees in this example. This angle can be visually assessed, or some machines can measure the angle.

Notice that the SDUN is hypoechoic and can be measured. In a small series (Roy et al., Int J Derm 2013, 52: 1-5), normal SDUN was 0.16 ± 0.1 cm. In a group of patients highly likely to have clubbing, the SDUN was 0.284 ± 0.02. We can say that any width greater than 0.25 cm is suspicious for clubbing. Notably, they reported that it was easy to see when the Lovibond angle became ≥ 180 degrees in all the clubbing patients. Thus, a quick measurement of the width of the SDUN and a visual assessment of the Lovibond angle are all that are needed to assess the strength of evidence for clubbing.