Pancreas and Spleen

It takes detailed knowledge of anatomy and pathophysiology to image these structures well.

PANCREAS

The pancreas is poorly seen during most IMBUS exams. However, knowing where it lies is essential for recognizing incidental pathology during a liver or abdominal aorta exam. The curvilinear probe is used.

There is no evidence that ultrasound screening for pancreatic cancer is beneficial. Guidelines exist for CT-visualized pancreatic lesions, depending on their size and whether they are cystic or solid. However, our views of the pancreas are indistinct in most clinic patients, and focal lesions are rare. Thus, any cystic or solid lesion we see with IMBUS needs CT or MR evaluation.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

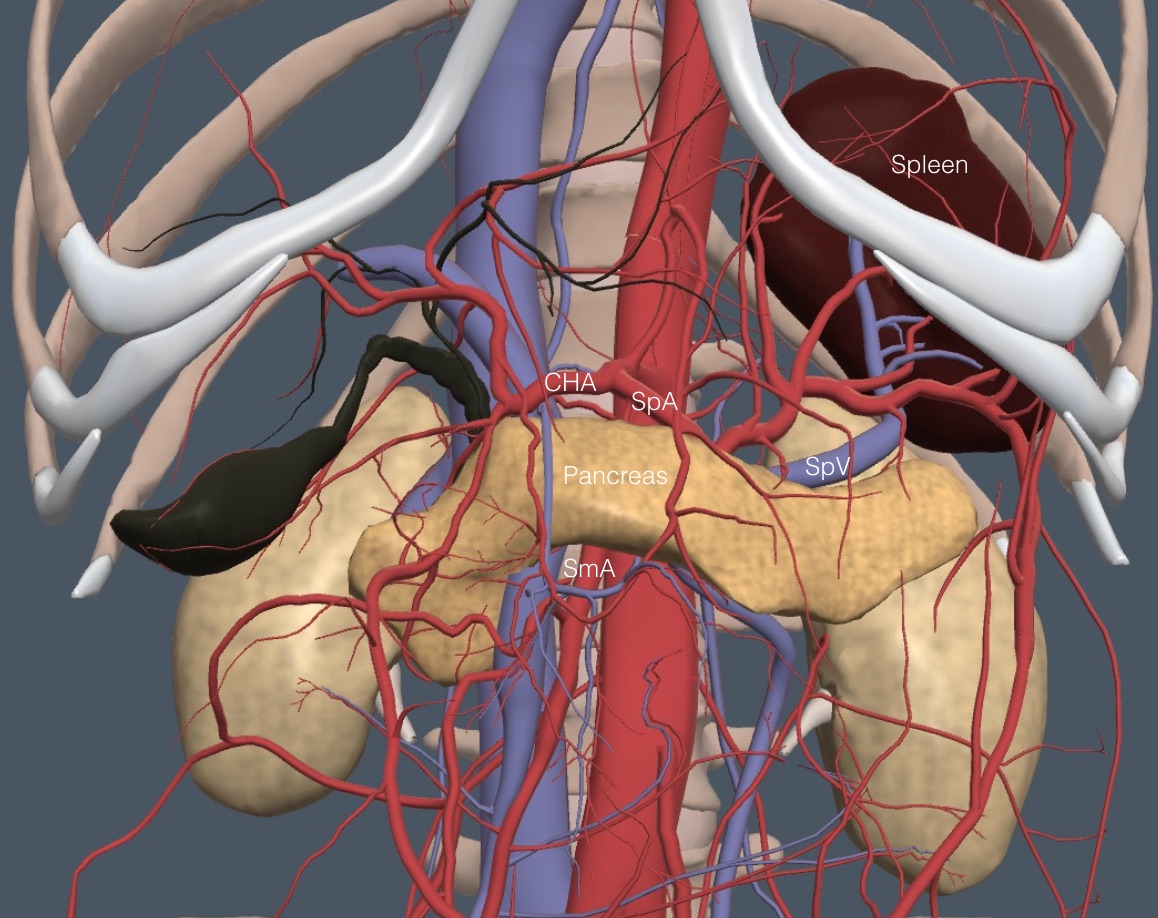

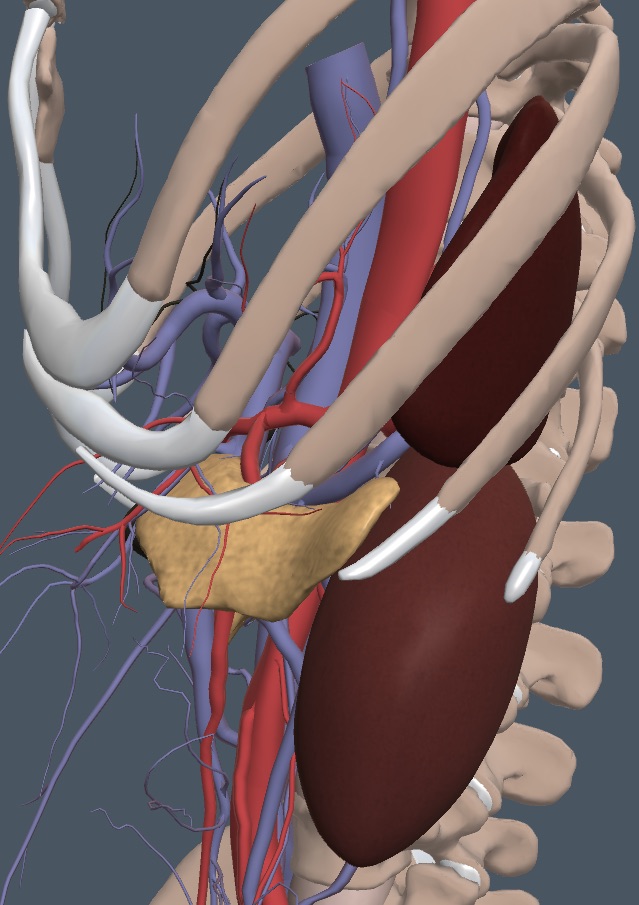

The splenic vein (SpV) is our critical landmark to the pancreas, which runs anterior to the splenic vein and posterior to the duodenum, transverse colon, and stomach. The following anatomy image removes the GI tract structures. It shows the unusual shape of the pancreas running from its head at the duodenum, transversely through its body, and then posteriorly and laterally into the tail, which ends near the spleen and left kidney.

The pancreas is primarily isoechoic with the surrounding tissues. It can be a little hypoechoic in younger patients and more hyperechoic in older and obese patients. It can look more “sparkly” than the liver during live viewing. The pancreas lies anterior to the SpV until it is out of view behind the stomach. In obese or gassy patients, keep the probe high in the epigastrium and have the patient hold a deep inspiration so the left liver lobe can be the acoustic window to scan down to the SpV and pancreas.

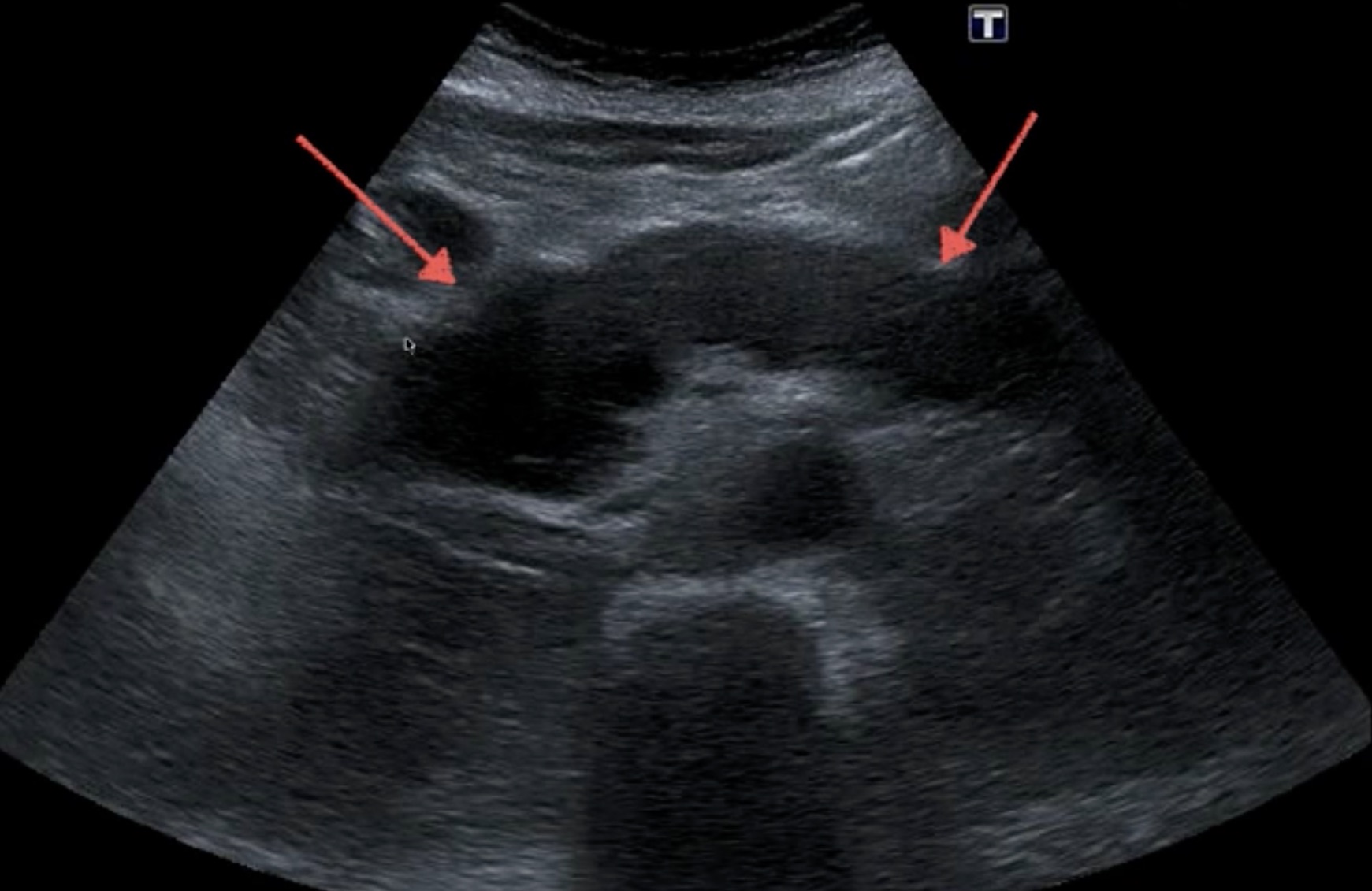

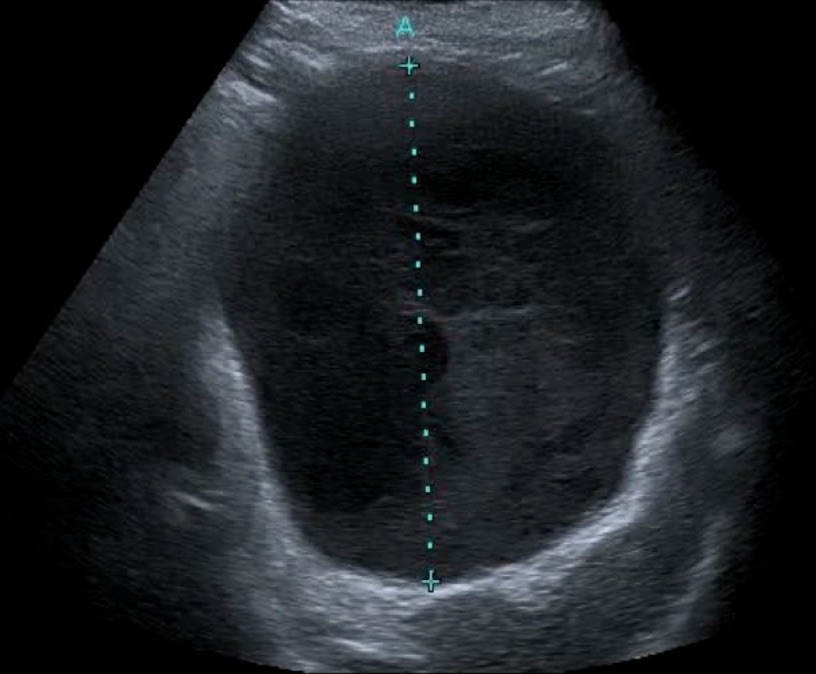

Here is a clip showing the SpV coming over the SmA with a normal pancreas anterior to the SpV. The stomach contents begin at the far right of the image.

Once the pancreas is identified, subtly angle caudad and slide from right to left to see as much pancreas as possible. The gastric antrum almost always obscures the tail.

The pancreas is about 2-3 cm deep throughout but thicker in the tail. There is a technique for viewing the tail of the pancreas from an intercostal view at the left mid-axillary line, but it is challenging to get the view in most adults, so we don’t consider it part of the IMBUS toolkit.

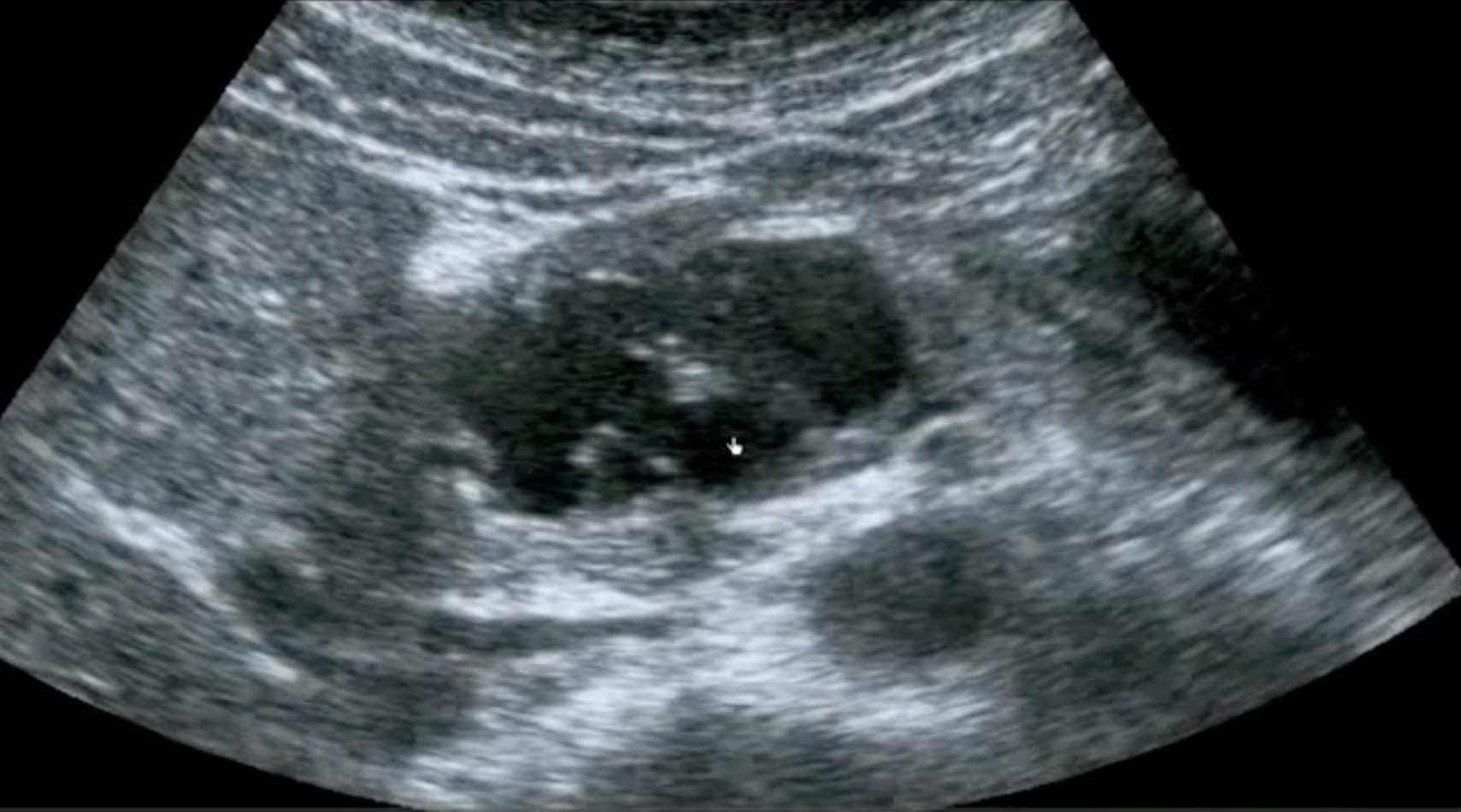

Acute pancreatitis usually causes ileus, making viewing the pancreas more difficult. Inflammation causes edema, resulting in an enlarged, hypoechoic pancreas. Here is a case of diffuse acute pancreatitis.

Pancreatitis can also be patchy and focal, in which case there is inhomogeneity of echogenicity, as in the following case.The later complications of pancreatitis, such as chronic pancreatitis and pseudocyst, are more pertinent to the clinic. Chronic pancreatitis is notable for the appearance of calcifications and increased echogenicity in the pancreas. The following case shows prominent calcifications.

Another characteristic feature of chronic pancreatitis is dilated pancreatic ducts, which may look like vessels but show no flow with color flow/power Doppler. Here are some dilated pancreatic ducts in chronic pancreatitis, along with calcifications.

A classic complication of pancreatitis is pseudocyst. Sometimes, it is an easy diagnosis, as in the following case of a 40-year-old woman still having pain after a second episode of acute pancreatitis. This is a large pseudocyst drained endoscopically into the upper gut with a stent.

True cysts in the pancreas may be benign or neoplastic (mucinous cystadenocarcinoma and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm). The details of the clinical situation are essential for diagnostic decision-making. Here is a multi-lobed cyst in the head of the pancreas that could be benign or malignant.

Pancreas tumors can be benign (cystadenoma or endocrine) or malignant (adenocarcinoma, cystadenocarcinoma, lymphoma, and neuroendocrine). This differential diagnosis makes solid lesions in the pancreas challenging to diagnose.

Here is a patient with a hypoechoic mass in the head of the pancreas. It was larger than 2 cm, so the prognosis was not good.

This next sizeable hypoechoic mass was in the distal body and tail of the pancreas.

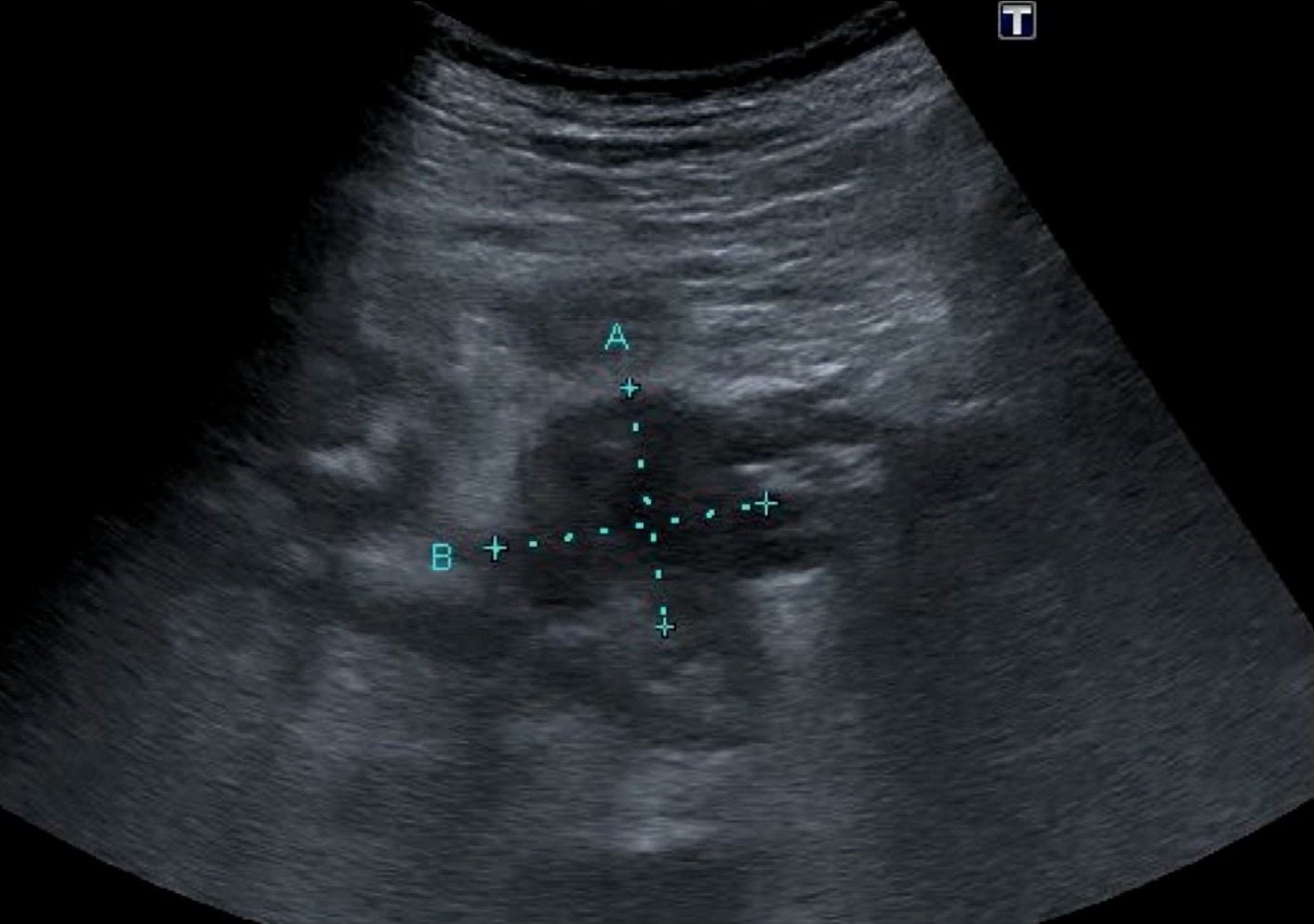

It is possible to detect pancreatic cancer at a stage when it is resectable for cure (< 2 cm with no nodes). That was the case in the following patient with a small hypoechoic lesion in the body of the pancreas.

SPLEEN

The spleen can’t be seen through the anterior abdomen because of the stomach. The spleen is semilunar or triangular and lies obliquely next to the ribs in the posterior left upper quadrant. The splenic hilum, where the SpV and the splenic artery enter and exit, is on the medial surface of the spleen.

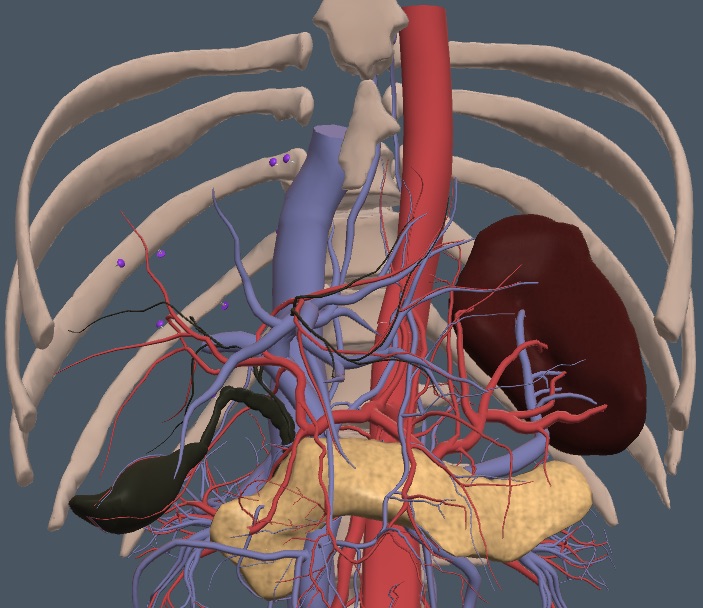

The window to the spleen can be small. It is always caudad of the lung and posterior to the stomach. The spleen is also cephalad and anterior to the retroperitoneal kidney. The right lateral decubitus patient position is standard for the spleen exam, but if this view is suboptimal, the standing patient position can improve the view. Whether the patient is standing, supine, or right lateral, find the phase of respiration where the spleen is best seen and have the patient stop breathing for several seconds so you can view a still organ. Here is the anatomy view of the splenic region as the probe would view things with the patient in the right lateral position.

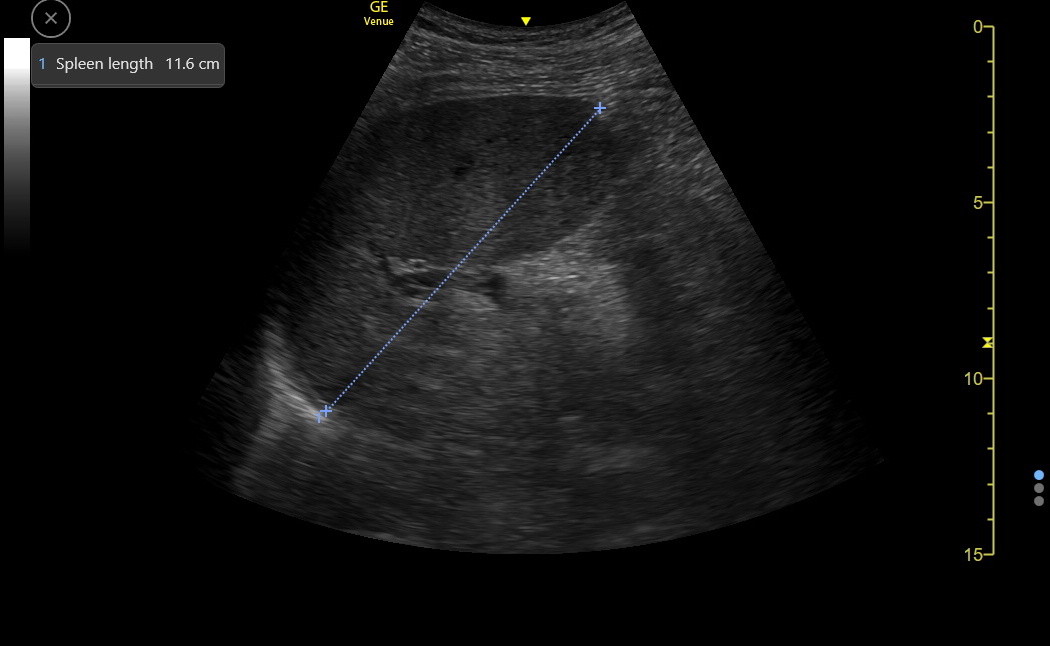

Use the intercostal spaces to locate the spleen because they are oriented roughly in the long axis of the spleen. Find an intercostal space at the right anterior axillary line and get the probe fully intercostal with the indicator toward the top of the spleen. Search below the lung curtain. If gas is seen, move an interspace more posteriorly. If the kidney is seen, move cephalad and an interspace more anteriorly. Make subtle adjustments to get the spleen long axis. Here is a normal-appearing spleen.

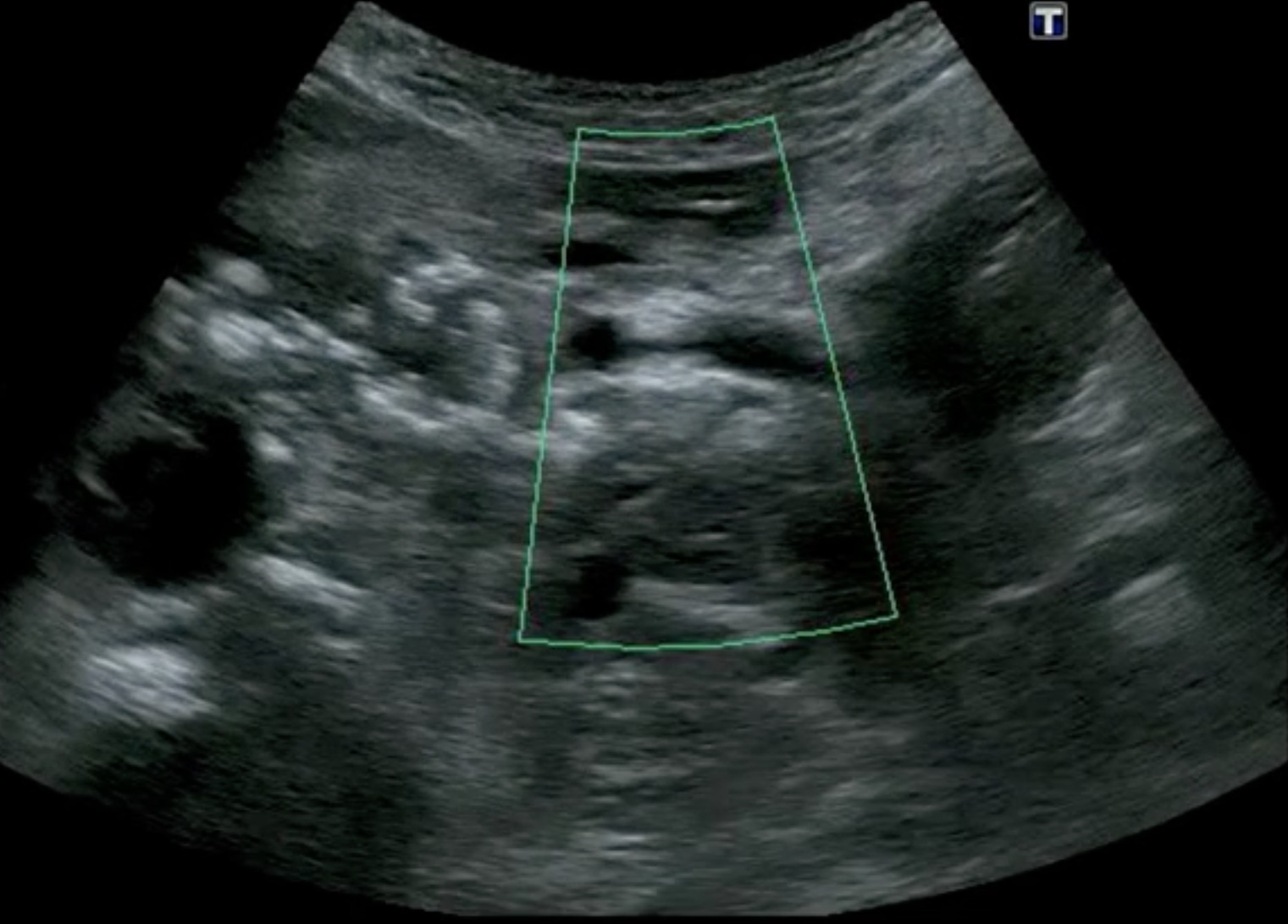

The spleen should be measured across the hilum, which occasionally needs color/power Doppler for identification. Here is PDI imaging of a normal spleen showing the hilar vessels.

Next is the correct measurement across the hilum of a borderline enlarged spleen.

The spleen varies with patient height, but spleens < 12 cm in length are normal, 12-16 cm length is mildly increased, 17-20 cm is moderately increased, and > 20 cm is severely increased. The spleen also “rounds up” as it becomes enlarged. A spleen that extends below the left kidney is probably enlarged. Here is a clip of an enlarged spleen extending below the left kidney.

Fan through the spleen in the long axis and confirm that it is homogenous in appearance with few visible vessels. The spleen's normal echogenicity is greater than that of the liver and kidney parenchyma.

Enlarged spleens are usually obvious, and the echo density may be abnormal because of the disease. Here is mild to moderate splenomegaly from chronic lymphoma.

The splenic vein may be enlarged at the hilum in patients with portal hypertension, as in the following example.

Also, near the hilum are accessory spleens, which are not rare. They are usually small, round, and isoechoic with the spleen. Their importance only arises when splenectomy is being considered. In the example below from a young clinic patient who recently had a traumatic laceration of the spleen, the accessory spleen is just above and to the right of the hilum in the image. Enlarged lymph nodes near the hilum can resemble accessory spleens.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

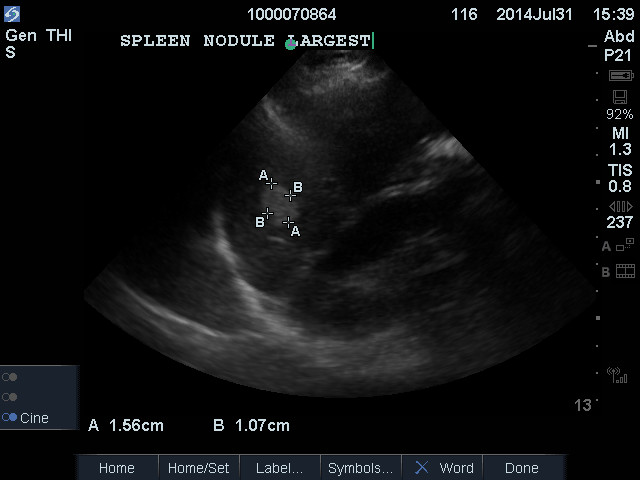

Discrete splenic lesions

Below is a brief discussion of the most significant lesions we might see in the spleen. Because such lesions are rare and hard to distinguish reliably with ultrasound, we almost always get confirmatory CT or MR.

Cysts of the spleen may be simple, acquired, and benign, as in the liver. Here is an example.

However, cysts may also be post-necrotic, infectious, and even neoplastic, so the accompanying clinical features must be considered.

Hemangiomas of the spleen occur and are smooth-bordered and hyperechoic (snowball in the spleen), as in the liver. Single such lesions are benign the great majority of the time.

Metastatic lesions in the spleen are rare but are occasionally hyperechoic, with a hypoechoic rim (target sign), so we look carefully at hyperechoic spleen lesions.

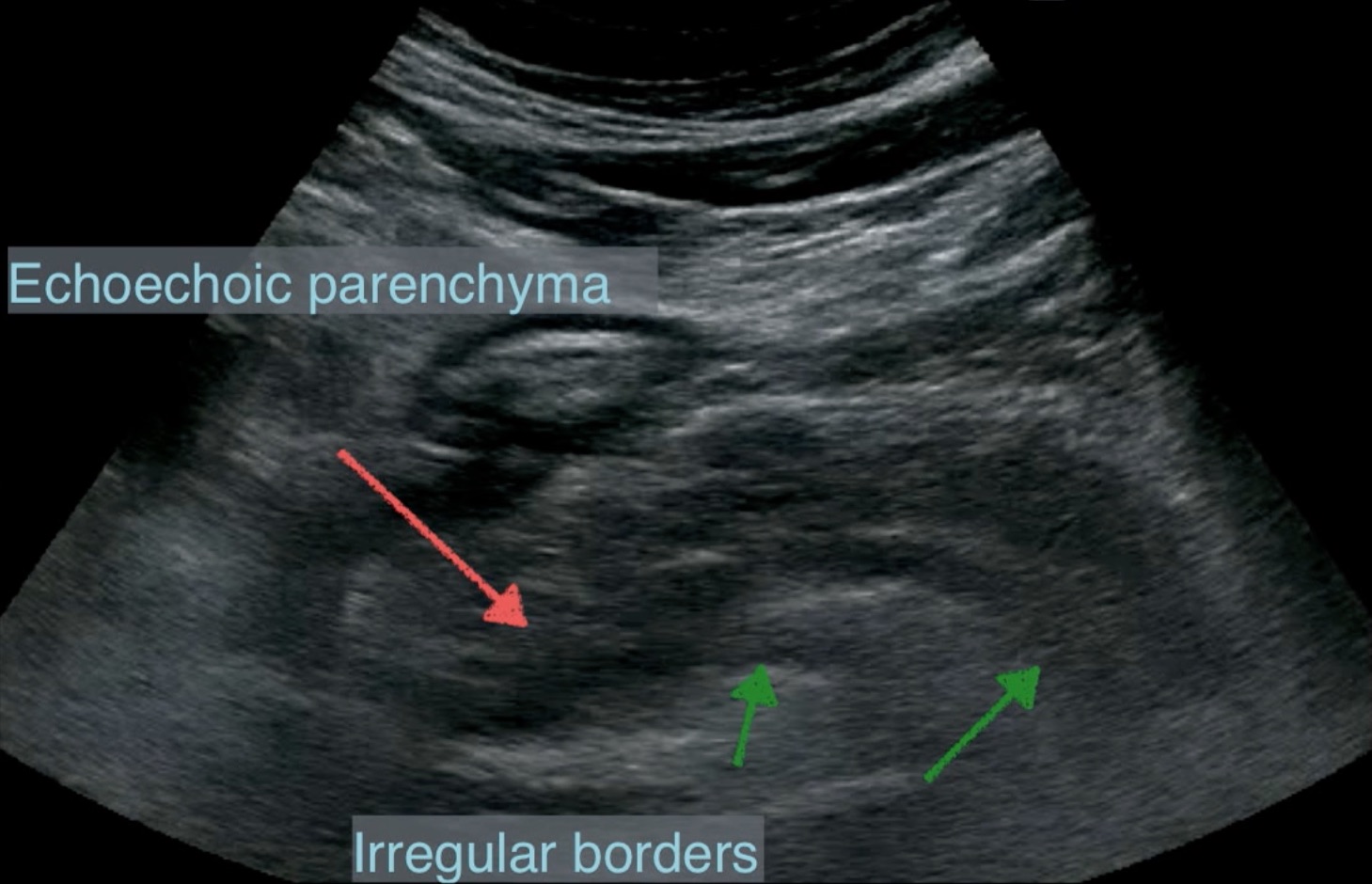

Splenic hamartomas (also called splenomas) are benign lesions that may cause concern about malignancy because they have hypoechoic areas. Imaging with CT/MR is required. Here is an example.

Many conditions cause calcification in the spleen. Some of these are the resolved phase of a disease, but occasionally, unusual chronic infections or even sarcoma and lymphoma can have calcification. The rest of the clinical findings become essential to figuring this out. Here is a clip from a typical case of splenic calcification.

Infarction and Hematoma: Acute left upper quadrant pain could be a splenic infarct from an embolus. A pyramid-shaped lesion with its base at the capsule would be typical, but sometimes, the lesion appears in the middle of the spleen because it abuts the opposite surface of the spleen. Infarctions can also vary significantly in size. Acute lesions are hypoechoic, but older lesions become more echogenic. An acute/subacute hematoma would be peripheral in the spleen with a density different from the normal parenchyma. Acute hematomas are hyperechoic.