Lymph Nodes

An IMBUS lymph node exam must be carefully performed and interpreted to avoid over- or under-reacting to these lumps.

Ultrasound is usually better than CT at finding and sizing lymph nodes in the neck, axilla, epitrochlear area, and groin. A general lymph node survey, whether traditional or IMBUS, has not been shown beneficial as part of a periodic physical but has anecdotally been useful in systemically ill patients who could have an infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic disease because an abnormal node might be biopsied to make a diagnosis. A physician needs good technique and knowledge of lymph node anatomy to perform such a survey.

Most patients who need an IMBUS lymph node exam come to the clinic after noticing a lump in the neck, armpit, or groin. If a lump is an abnormal node, a more general node survey might be done to determine if the lymphadenopathy is generalized. The differential diagnosis for generalized lymphadenopathy is different from that of localized lymphadenopathy.

The most frequent enlarged node in the clinic is a neck node, most of which are a reaction to head or neck infection. Yet, malignancy is the fear, so the size and character of nodes are evaluated carefully. In the primary care setting, unexplained lymphadenopathy has only about a 1% chance of malignancy, but the failure of node regression over four weeks increases the chance of malignancy.

ANATOMY

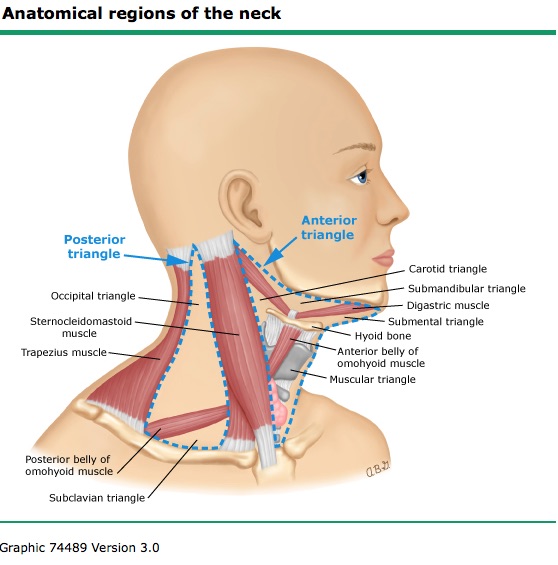

The neck region is divided into Anterior and Posterior triangles based on the sternocleidomastoid muscle, as shown in the following diagram. Supraclavicular nodes are found in the small Subclavian triangle.

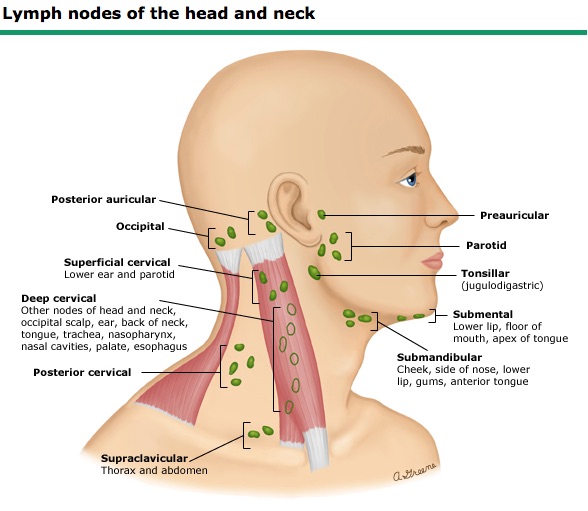

The following image shows the location of lymph node groups in the neck. There are nodes superficial and deep to the sternocleidomastoid. Some nodes are near the carotid artery and internal jugular vein. For a neck survey, the probe is moved in a transverse orientation up and down the neck from medial to lateral, like a systematic palpation exam would be performed.

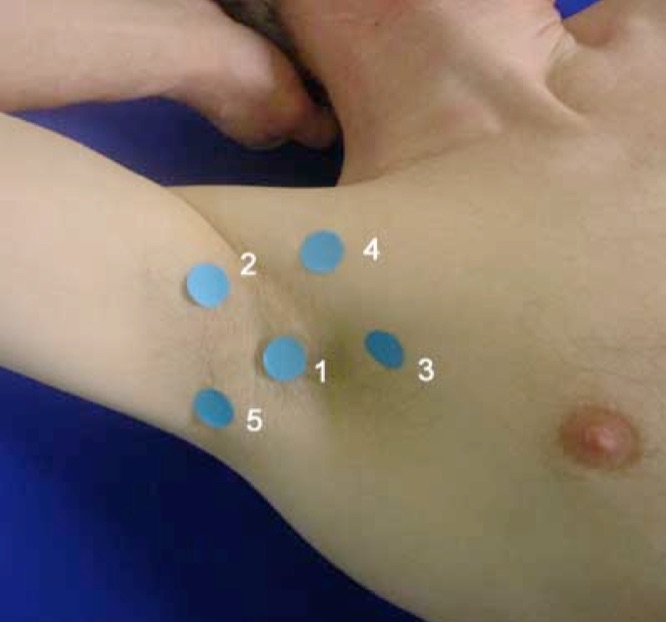

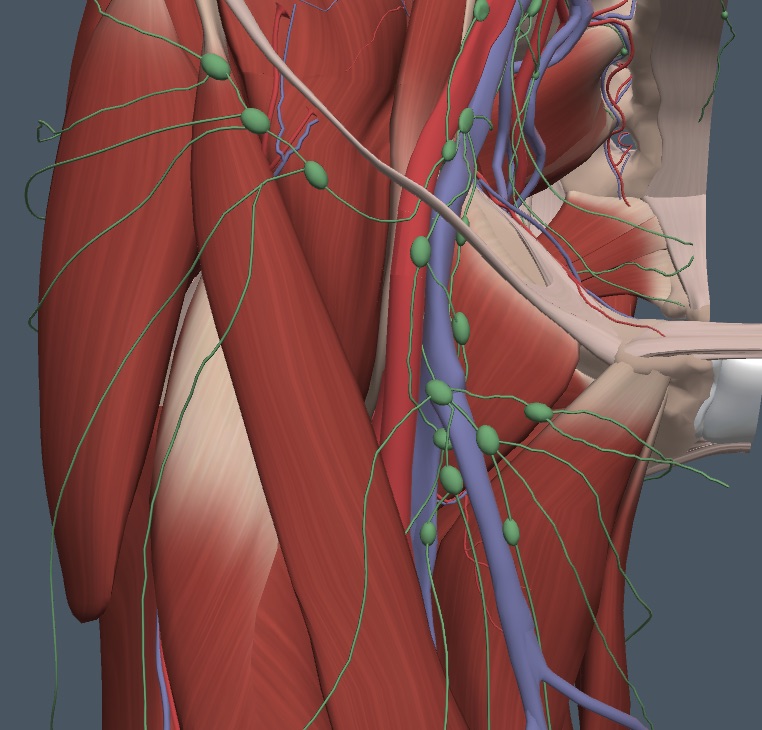

The axillary region has nodes on the lateral chest, high in the axilla, and on the upper inner arm, as in the following image. A systematic survey of axillary nodes would rarely be done with IMBUS. However, when a patient has noticed a lump in this area, it is essential to know where to look for additional nodes in the region.

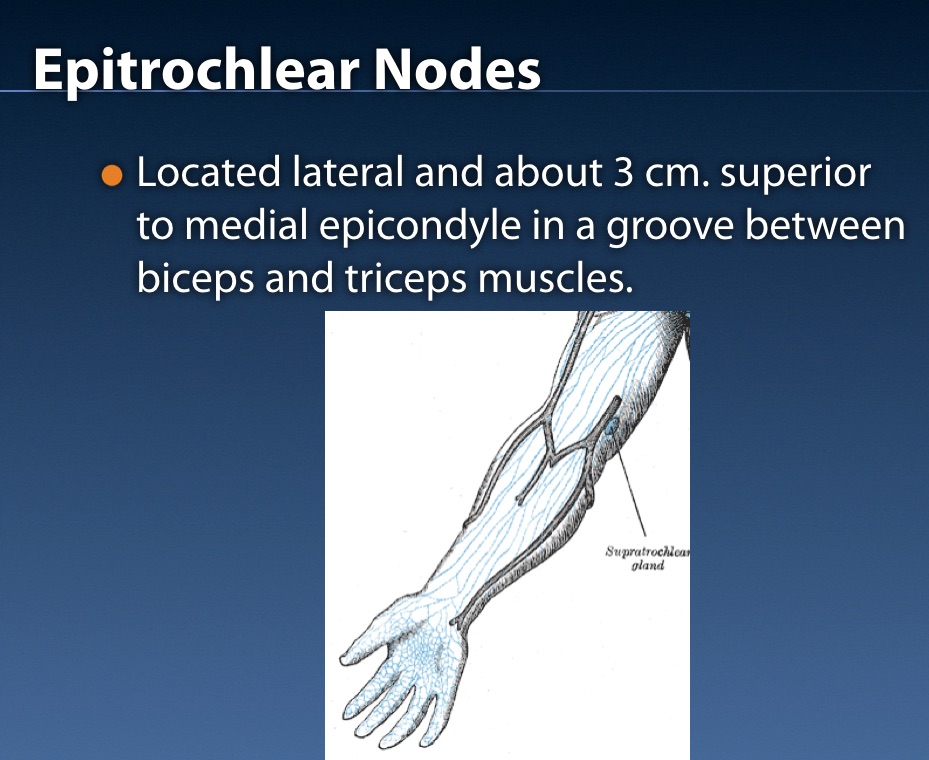

The epitrochlear region is small, and many normal patients have only tiny nodes in this location. However, an enlarged node indicates either generalized lymphadenopathy or an inflammatory condition in the lower arm, which should be obvious. The following image shows the location of potential epitrochlear (supratrochlear) nodes in the groove just medial to the biceps muscle. Notice the proximity of the node group to the basilic vein near the medial epicondyle.

Groin nodes can be inguinal, which are located near the inguinal ligament and drain the lower retro-peritoneum, pelvis, and genitals, or they can be femoral, which are located anterior and medial to the common femoral and great saphenous veins. The femoral nodes drain the leg and, occasionally, the genitals. The following diagram shows the inguinal and femoral node groups.

TECHNIQUE

Lymph nodes are best evaluated with the linear probe and an exam type optimized for good detail and low Nyquist limits. All the peripheral node regions are best examined with the patient in the supine position. The view of each node should be optimized with depth and focus position so details of shape and texture can be observed. To be consistent amongst physicians and between follow-up exams, the probe should be rotated to find the largest dimension of the node, which is considered the “length.” The probe is then rotated 90 degrees to measure the “width” and “depth” of the node. These dimensions may have no relationship to the traditional parasagittal or transverse planes on the body. Color power Doppler should be applied to assess the vascularity.

NORMAL NODES

Based on a single characteristic, it is impossible to be sure that a node is normal or abnormal (or certainly reactive versus malignant). However, integrating the findings with the rest of the clinical story helps the physician make good decisions.

Normal nodes appear the same in any of the four regions IMBUS can evaluate. They are < 1.0 cm (often < 0.5 cm) long, oval/elliptical, with a hyperechoic central hilum. Color/power Doppler shows only a little flow in the hilum. The periphery of the node has moderate to low echogenicity, and the margins of the node should be clear and smooth. The following image is a normal neck node in an asymptomatic patient just anterior to the internal jugular vein. This node measured 0.9 cm in length.

ABNORMAL NODES

Increased size usually prompts a node exam, but size alone does not distinguish reactive from malignant nodes. Every malignant node begins small.

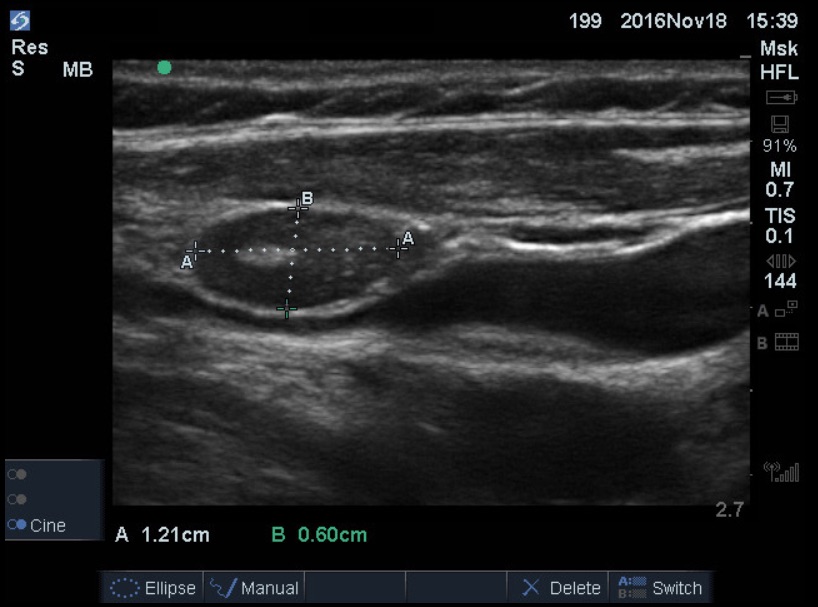

A node that is ≥ 1 cm in maximum length is enlarged. In general, reactive nodes should maintain an oval/elliptical shape and have a preserved hyperechoic hilum, but the periphery of the node may be more hypoechoic than normal. Color/power Doppler flow may be increased at the hilum of a reactive node, but the node's margins should still be sharp and smooth. The following image shows a modestly enlarged node that was proven to be reactive with careful follow-up.

The next node was more worrisome to the physician because it was a little larger and rounder. It was in the groin and had been present for over a month.

There was no apparent inflammatory focus in the leg or groin. The node seemed to have an irregular border. The periphery was more hypoechoic than normal. Color/power Doppler flow was increased in the hilum. After seeing the surgeon several weeks later, with the persistence of the node, FNA was performed, and no malignancy was found. Thus, differentiating reactive from malignant nodes is complex, and a biopsy is sometimes needed.

Malignant nodes typically become rounded or irregularly shaped and are usually markedly hypoechoic, although a few types of tumors can create hyperechoic nodes. Color/power Doppler flow can be increased in various places in the node. The following image is a neck node proven to be lymphoma. It was a 3 cm node, and while the margin was distinct and smooth, the hilum was obliterated, and the node was very hypoechoic. There was also scattered color flow throughout the node.

The following clip is from a non-smoking clinic patient who noticed a lump in the neck. This hypoechoic node was 3.0 cm long, modestly rounded, and had no hilar vessels. Biopsy revealed a squamous cell carcinoma related to HPV. This was the only lesion on PET/CT scanning.

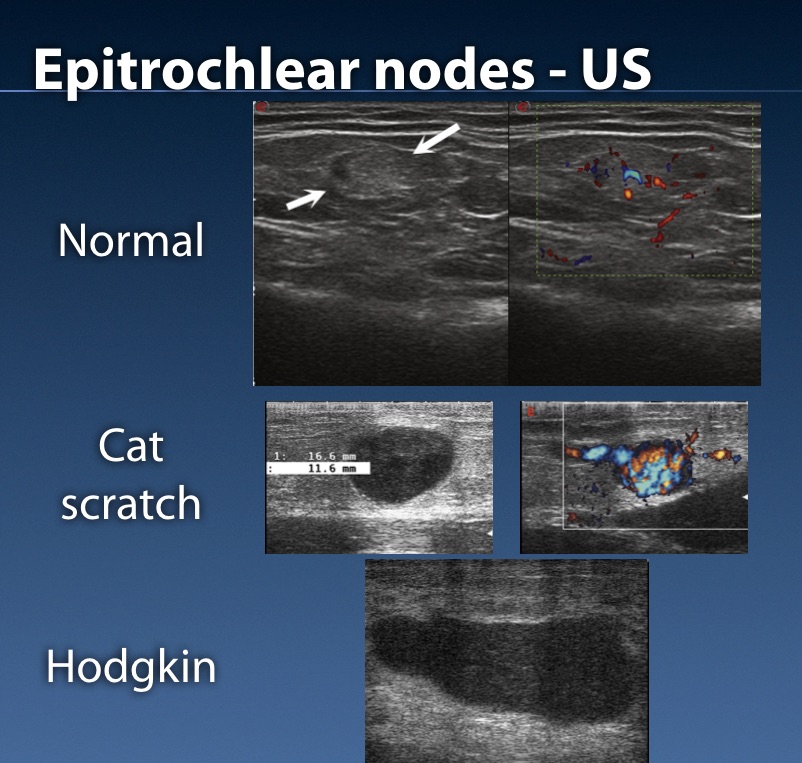

The following composite image shows epitrochlear nodes ranging from normal to inflammatory and then malignant. It is challenging to differentiate a reactive cat scratch disease node from a malignant node. The rest of the clinical story and follow-up are usually necessary to separate reactive from malignant nodes.

The following case was a 72-year-old man who came to the clinic with a URI. Several lumps were felt in the right supraclavicular region. The clip shows a round shape, a more hypoechoic texture than normal, no hilum, and some increased Color. The biopsy showed follicular lymphoma.

An older woman noticed lumps in her inguinal region. Here is the color Doppler of the largest node in the group. The color Doppler flow is increased at the hilum and into the parenchyma of the node.

It is impossible to determine whether these are reactive or malignant nodes. Given the overall appearance of the group and without an obvious leg, genital, or intra-abdominal inflammation, waiting a month for regression was probably not the right approach for this patient. So, an immediate CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained, but this showed no pathology to explain the nodes. Only longer-term follow-up will differentiate reactive from malignant nodes, and a biopsy may be needed.

IMBUS APPROACH TO NODES

1. Each enlarged node should be measured for length, width, and depth. The other node characteristics should be noted, including Color/power Doppler flow, and the images/clips should be saved in case a follow-up comparison is needed.

2. A patient with a modestly enlarged node with other characteristics still appearing normal can be reassured by the extremely low likelihood that this node is malignant, especially if the node is in the neck and the patient is younger. But, over the next month, each patient should note whether the node decreases or disappears (avoiding vigorous daily palpation). With a less reliable patient, a follow-up visit should be scheduled. The patient must return for re-imaging if the node does not regress. Reactive nodes do not have to disappear entirely in a month but should not grow unless the inflammatory condition continues. An apparent reduction in size over a month strongly supports a reactive node.

3. Older patients, particularly smokers, with neck nodes and an absence of recent infections in the head/neck are more suspicious for cancer. A 4-week repeat exam might be appropriate, but ENT consultation without a 4-week wait would be justified with any other atypical characteristic beyond size. It would usually be wise to call ENT and decide about a CT scan before the office consultation.

4. The larger and more abnormal a node appears, the greater the concern for malignancy. Integrating all the node findings with the rest of the clinical story will often prompt immediate ENT or surgical consultation (with CT imaging).

5. Generalized lymphadenopathy has a broad differential diagnosis of infectious, inflammatory, and neoplastic conditions. Integration with the rest of the clinical findings is essential, but a lymph node biopsy may contribute to the diagnosis, and IMBUS can help identify the best node to biopsy.