Abdominal Hernias, External

Abdomninal hernias are common, and palpation is sometimes inadequate for diagnosis. IMBUS can aid the diagnosis.

External abdominal wall hernias are frequent and represent one of the most common reasons for emergent surgery in patients over 50 years old. They are a protrusion, or bulging, of a structure through some part of the anterior abdominal wall. The protruding structure is most commonly fat but can also be bowel. Hernias may occur only with increased intra-abdominal pressure and recede when the pressure returns to normal, or they may persist. When a hernia is persistent at rest, but probe pressure moves the contents back into the abdomen, the hernia is reducible. If probe pressure does not entirely reduce the hernia, it is called non-reducible or partially reducible. The term incarcerated should not be used. Strangulation is an appropriate term, but it is a clinical-pathological term that means tissue harm is occurring. IMBUS cannot reliably determine strangulation, although strangulated fat usually becomes more hyperechoic.

Inguinal hernias are most common, followed by femoral, ventral (including Spigelian), and incisional. Incisional hernias will not be discussed in this chapter. Many hernias are asymptomatic, so be cautious attributing chronic, vague symptoms to a patient’s hernia.

TECHNIQUE

The linear probe is used with a musculoskeletal preset. However, with very obese patients, a curvilinear probe might be needed, although the lower frequency means that smaller hernias will probably be missed. The standing patient position gives excellent views and can be a quicker and easier exam for many patients. However, the supine position is also a standard approach that may be superior in an obese patient because it can be easier to lift the fatty tissue out of the way in the supine position. If a femoral hernia is not a consideration, a patient only needs to loosen the pants and lower them slightly. If a femoral hernia is a possibility, the pants must be lowered, similar to a DVT exam.

Intermittent patient Valsalva maneuver is almost always needed, although it is hard to standardize this maneuver. Coughing is not an optimal method for the IMBUS exam. “Hold your breath and strain like you are lifting something heavy” is an instruction that can work. “Push down (bear down) like you are trying to move your bowels” isn’t quite as good.

Anatomy knowledge and a systematic approach are required to evaluate patients with lower abdominal pain or bulges. Even in a patient with no midline pain or bulge, beginning in the midline just below the umbilicus helps get the depth and gain correct for a patient and starts the anatomic survey.

VENTRAL HERNIAS

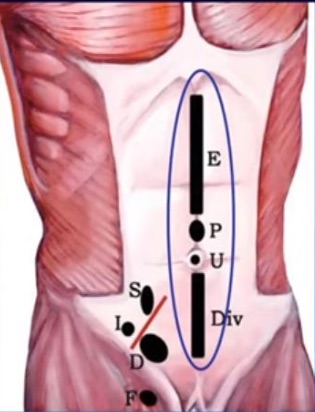

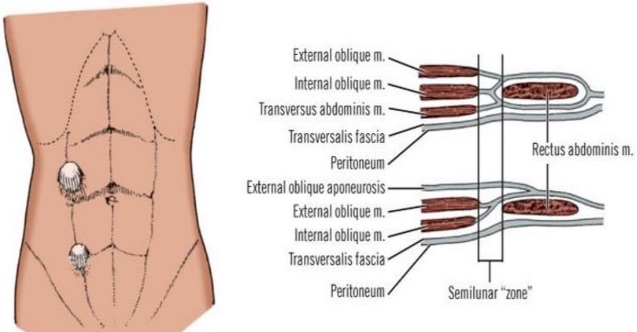

More common in women than men, these hernias occur anywhere in the midline through a defect in the linea alba. The following diagram shows the locations of what would be called epigastric, paraumbilical, umbilical, and hypogastric ventral hernias. The Spigellian, Indirect inguinal, Direct inguinal, and Femoral hernia locations are also noted.

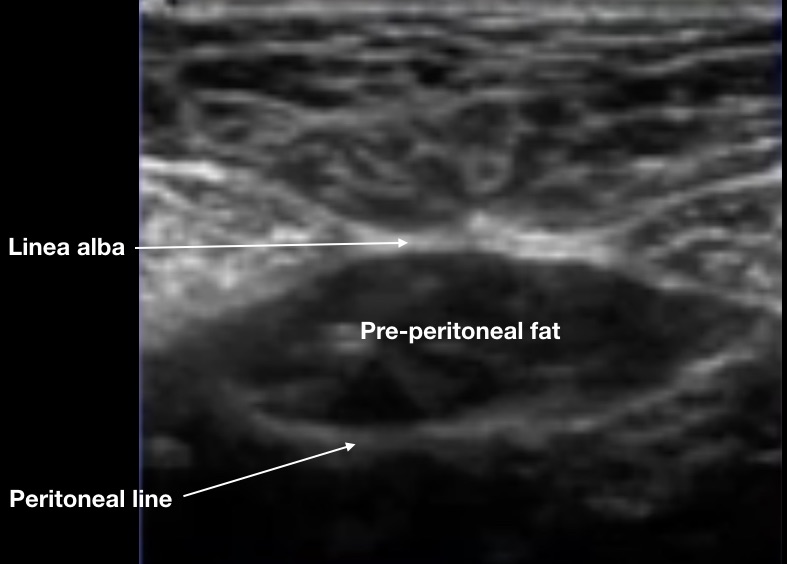

Here is a clip of a normal midline in an average-weight older man. The transverse view shows the epidermis, dermis, and adipose layers down to 1.25 cm, ending at a hyperechoic fascia anterior to the rectus muscles. The upward-sloping posterior fascia of the rectus muscle meets the anterior fascia at the midline to form the linea alba. The hypoechoic triangle below the linea alba is a pre-peritoneal fat collection that is present in all but the leanest patients. Bowel with peristalsis is seen posterior to the peritoneum.

Diastasis recti is a common condition that suggests a ventral hernia but rarely needs repair. It is a widening of the central gap between the rectus muscles. When a patient raises her head or partially sits up, there is a midline bulge. However, while the linea alba and the intra-abdominal contents bulge upwards, there is no defect in the linea alba or the peritoneum. The following image shows bulging diastasis recti with the rectus muscles spread far enough apart that they are barely in the image.

The earliest form of a true ventral hernia is a “pre-peritoneal” hernia. Many patients, including the clip above, have a collection of fat between the linea alba and the peritoneal lining. Here is a close-up still image.

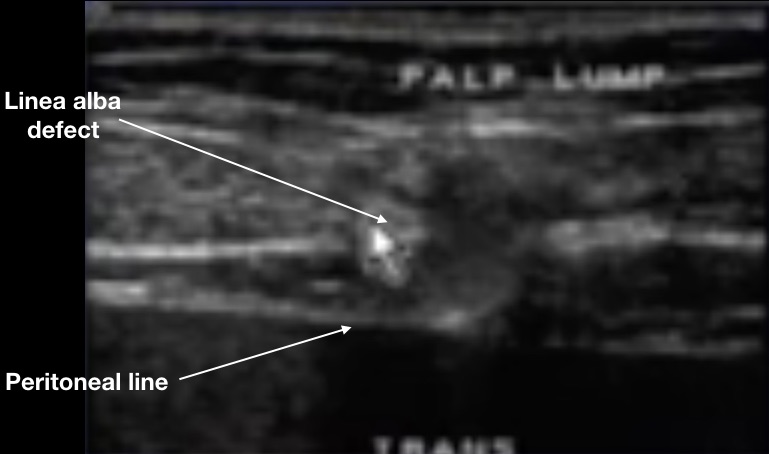

When a defect occurs in the linea alba, this pre-peritoneal fat can be the first thing to bulge up, causing the patient to feel a lump. Yet, the peritoneal lining is still intact, so abdominal contents are not in the hernia. Here is a still image of a pre-peritoneal ventral hernia with Valsalva.

The next clinic patient had midline symptoms, but the surgeon’s exam was equivocal. Fat is seen coming up through the linea alba, but the peritoneal line seemed intact. A pre-peritoneal hernia could be considered, but the fat moving through the linea alba seems more significant than usual, so this is probably a true ventral hernia.

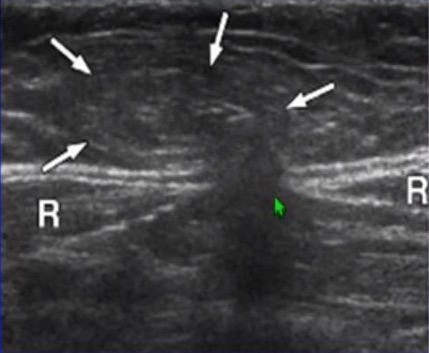

The following image was taken with a transverse probe position just above the umbilicus in an older man. The two rectus muscles are noted with an “R.” The green arrow points to the linea alba defect, and the white arrows point to the abdominal contents (primarily fat) coming up as a bulge.

Eventually, ventral hernias can become large, contain fat and bowel, be non-reducible, and strangulate. The following clip shows a non-reducible paraumbilical hernia, still mainly containing fat. The two white arrows note this hernia's wide neck, making it less likely to strangulate than a narrow-necked hernia.

THE INFERIOR EPIGASTRIC ARTERY

An important anatomic landmark for the next three hernias is the inferior epigastric artery (IEA), An important anatomic landmark for the next three hernias is the inferior epigastric artery (IEA), which originates from the external iliac at the level of the inguinal ligament. This artery moves acutely anteriorly and then runs superficially and diagonally to the ipsilateral rectus muscle. The IEA continues to run cephalad in the rectus muscle. In the following clip, the probe was placed over the right rectus muscle, just caudad of the umbilicus. Color visualized the IEA in the posterior center of the rectus.

SPIGELIAN HERNIA

As the probe moves caudad on the rectus muscle, the IEA moves out to the lateral margin of the muscle to begin moving diagonally toward the external iliac artery. Here is the IEA (with power Doppler) near the lateral edge of the rectus muscle.

This location near the lateral edge of the rectus is a landmark for the semilunar zone below the umbilicus, shown in the following diagram. This fascial region may be a weak point that allows a herniation called a Spigelian hernia. Spigelian hernias are rarer cephalad of the umbilicus.

A Spigelian hernia can cause pain/bulging at the lateral margin of a rectus muscle. These hernias rarely strangulate. When a patient has pain or a bulge near the lateral margin of a lower rectus muscle, find the IEA at the lateral rectus muscle and have the patient perform a Valsalva maneuver. A dynamic hernia may be seen lateral to the vessels, as in the following image.

INDIRECT INGUINAL HERNIA

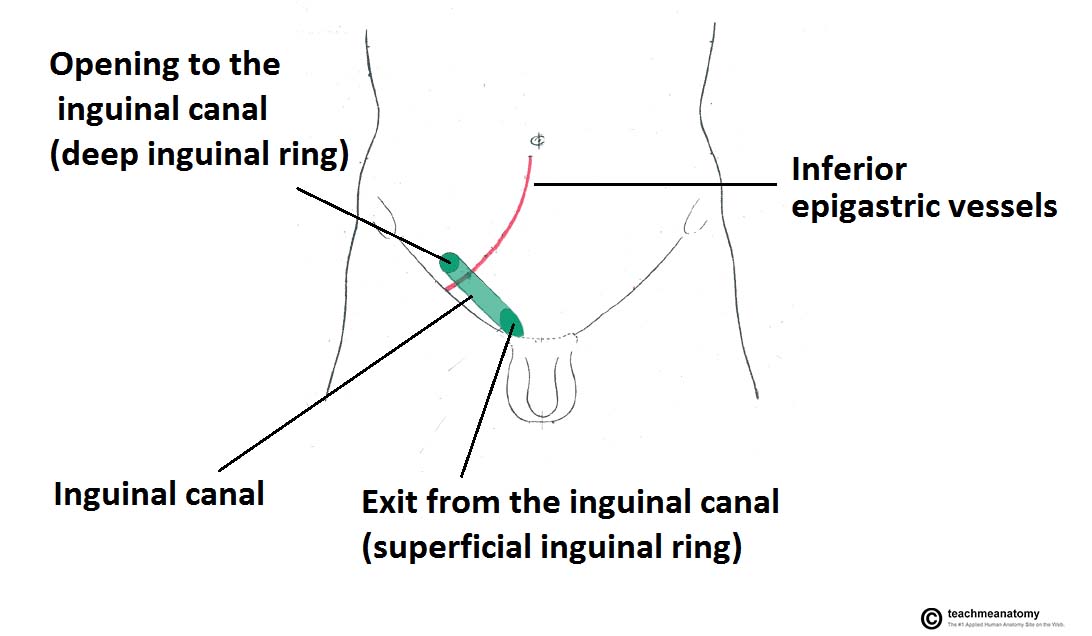

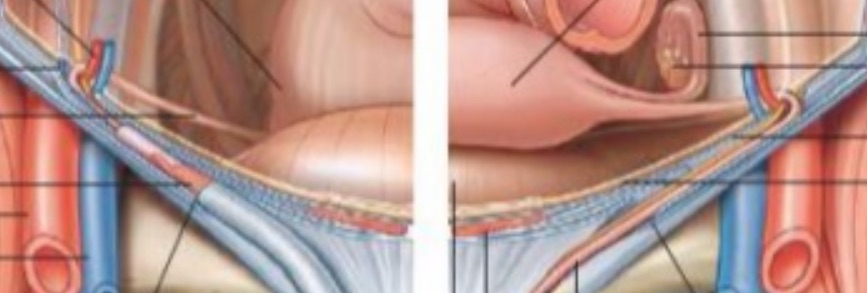

The inguinal canal is essential for both sexes, and some anatomical details are critical for dealing with hernias in this canal. Here is a simple anatomy overview.

The canal is parallel to, but slightly cephalad of, the inguinal ligament. The canal has an opening near the lateral pubis called the superficial (external) ring and an opening into the retroperitoneal space called the deep (internal) ring. This deep ring is just lateral and posterior to the IEA at this location.

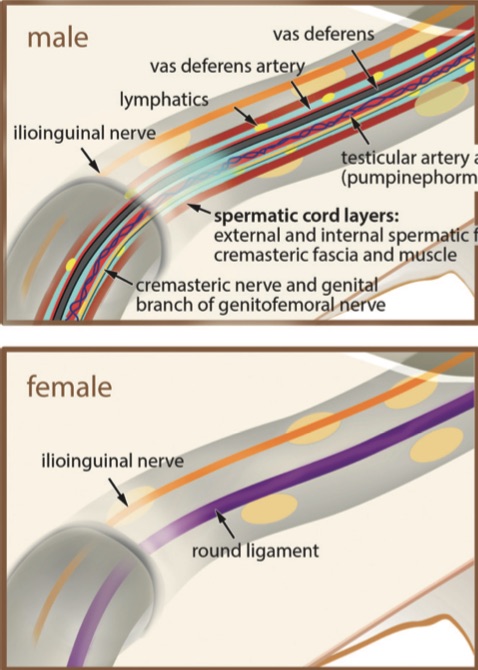

The following diagram shows the differences in the canal content between males and females.

The male spermatic cord contains the vas deferens, small muscles, arteries, veins, and nerves. The female canal contains only the round ligament of the uterus (ending in the labia majora) and a nerve. Consequently, the male inguinal canal has a greater diameter but is still only several mm wide.

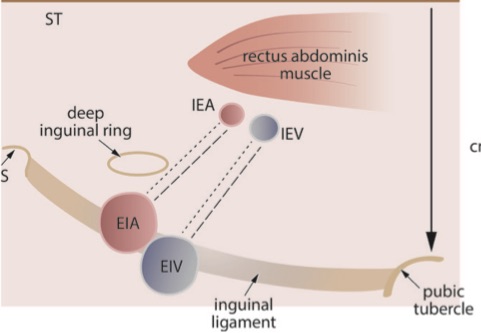

The location of the deep ring lateral and posterior to the IEA is critical for the IMBUS exam, and a systematic approach is necessary to find the right location. The following diagram shows a bit more detail about the area.

The IEA originates from the iliac artery at the level of the inguinal ligament. Depending on the patient's height, the deep ring is 1.0-2.0 cm cephalad of the IEA origin. The ring is in the retroperitoneal space, so if bowel is seen posterior to the IEA, the location is too cephalad.

As soon as the canal contents pass through the deep ring, they turn immediately medial. The left side of the following diagram shows the vas deferens running retroperitoneal to connect to the seminal vesicles near the prostate. In contrast, the right side of the diagram shows the round ligament connecting to the uterus near the origin of the fallopian tube.

Indirect inguinal hernias are the most common hernia in males because the descent of the testicles makes the canals larger and more prone to herniation. The right testicle usually descends later than the left in the fetus, which is blamed for making right indirect inguinal hernias more common in males. Since the inguinal canal in females does not enlarge, indirect inguinal hernias are rare.

If an indirect inguinal hernia becomes large enough in males, the contents can fully traverse the canal, exit through the superficial ring, and descend into the scrotum. Large indirect inguinal hernias are relatively easy to diagnose the traditional way. IMBUS is only essential for finding smaller, symptomatic hernias partway into the inguinal canal.

Method: The IMBUS hernia exam is helpful for symptomatic patients with equivocal or negative palpation exams and needs to be carefully performed to minimize false positive and negative errors. The following is a systematic approach.

Step 1: Before getting any gel on the area, locate the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle to estimate the orientation of the inguinal ligament and canal.

Step 2: Place the probe with gel about midway on the line between the two bony landmarks and locate the iliofemoral vessels. Adjust the depth so the vessels are toward the bottom of the sector. Then, find the IEA as it flows anteriorly from the iliac artery, as in the following clip. The inguinal ligament is the hyperechoic, loosely organized tissue anterior to the vessels.

Step 3: Slowly slide toward the umbilicus, which keeps the probe parallel to the ligament. Keep the IEA in the center of the sector and watch for the inguinal canal to appear anterior to the IEA. The deep ring will be just lateral and posterior to the IEA in this location. The probe has moved too far if bowel appears posterior to the IEA. Here is a clip of the correct location in a male. The inguinal canal is a mixed echogenicity, tubular structure just anterior to the IEA, and the deep ring is an indistinct, hypoechoic area lateral and posterior to the artery.

Here is the correct location for a female. The inguinal canal is thinner, and the deep ring is less conspicuous, but both are still visible.

Practical Note: The inguinal canal and the deep ring are subtle structures that require experience to recognize quickly. A clinically meaningful indirect inguinal hernia will be noticed if the physician begins parallel to the line between the two bony landmarks at the origin of the IEA and then slides toward the umbilicus but stops before the bowel appears below the peritoneum.

Once the deep ring and canal are identified, have the patient Valsalva and watch for contents to bulge up lateral to the inferior epigastric artery. Hernias that are more than trace will have contents that flow over the IEA in the medial direction. With equivocal findings, viewing the beginning portion of the inguinal canal in cross-section may be helpful. It is important to use light pressure, or the probe may compress the inguinal canal and obscure a hernia. Next is a modest right indirect inguinal hernia with fat entering the canal anterior to the IEA.

Here is a larger right indirect inguinal hernia with fat entering a fluid-containing inguinal canal. Fluid is relatively common in the canal in patients with inguinal hernias. The hernia is sliding on top of the spermatic cord. There can also be cysts of the spermatic cord, but there would be no tissue sliding up the canal from the abdomen.

Lipomas can also occur on the spermatic cord and might be confused with a hernia, but no tissue enters the deep ring. If a Valsalva maneuver shows no tissue entering from the deep ring, a lipoma could be suspected, but a formal ultrasound would probably be needed for confirmation.

DIRECT INGUINAL HERNIA

Most frequent in older men, these hernias are initially a bulge and then a defect in the “conjoint tendon” (the joining of all the lateral abdominal muscles into one tendon at the caudal, medial abdomen). Direct inguinal hernias are less likely to strangulate compared to indirect inguinal hernias. When there is only a symptomatic bulging of the conjoint tendon, without a defect in the tissue, the term “sports hernia” is used. Traditionally, direct inguinal hernias occur in Hesselbach triangle, bounded by the rectus muscle, the inguinal ligament, and the IEA. But, for the IMBUS exam, the physician remembers that direct inguinal hernias bulge anteriorly on the medial side of the IEA.

Direct inguinal hernias do not involve the inguinal canal but bulge anteriorly through the lower abdominal wall. Thus, the probe is moved medially from the indirect hernia position and positioned transversely on the lower abdomen, placing the IEA slightly lateral on the screen. If a patient has specific pain or a bulge in this area, the probe will also be placed right in that location. A Valsalva maneuver will usually be needed. The following clip shows a mild to moderate size right direct inguinal hernia bulging medial to the right IEA. This hernia was just cephalad of the inguinal ligament, so the iliac and inferior epigastric arteries and veins were visible lateral to the hernia. This hernia did reduce.

Finally, here is a large direct inguinal hernia that was partially reducible, but bowel moved up into the hernia with Valsalva at the end of the clip.

FEMORAL HERNIA

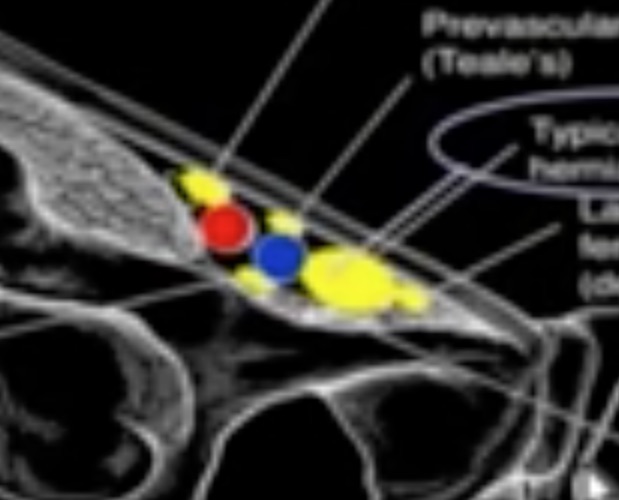

Femoral hernias are more common in women and increase with multiparity. These hernias can extend into the medial thigh, contain fat or bowel, and strangulate. Most femoral hernias come through the femoral ring medial to the common femoral vein. This location is familiar because of IMBUS DVT exams. However, a femoral hernia can infrequently appear slightly lateral or medial to this location, as in the following diagram (the yellow blobs).

Find the common femoral vein above the junction of the great saphenous vein. The area medial to the common femoral vein normally contains lymph nodes, connective tissue, and fat. A Valsalva maneuver is needed to see the moving hernia. The following shows a very small femoral hernia appearing anterior and slightly medial to the right common femoral vein.

This last clip has the right common femoral vein at the left edge of the screen (the white arrow pointing up). The arrow from the top points to a femoral hernia that is only partly reducible and then enlarges with bowel after a Valsalva.

Sometimes, a parasagittal probe position can help confirm a femoral hernia descending from above because of the longitudinal orientation of the hernia sack.