Kidneys and Adrenal Glands

IMBUS of the kidneys is essential in the hospital and clinic. Adrenal gland abnormalities can be seen incidentally when the kidneys are imaged.

IMBUS of the kidneys is most frequently needed in the clinic for suspected hydronephrosis. However, it is essential to identify some additional kidney diseases. The adrenal glands are small and near the kidneys, so large lesions in the adrenal need to be recognized during a kidney exam. Ultrasound is not sensitive for evaluating adrenal glands, so we do not need to worry about increasing the diagnosis of small incidentalomas. However, spotting a larger adrenal mass can be important for some patients.

KIDNEY ANATOMY

MACRO ANATOMY:

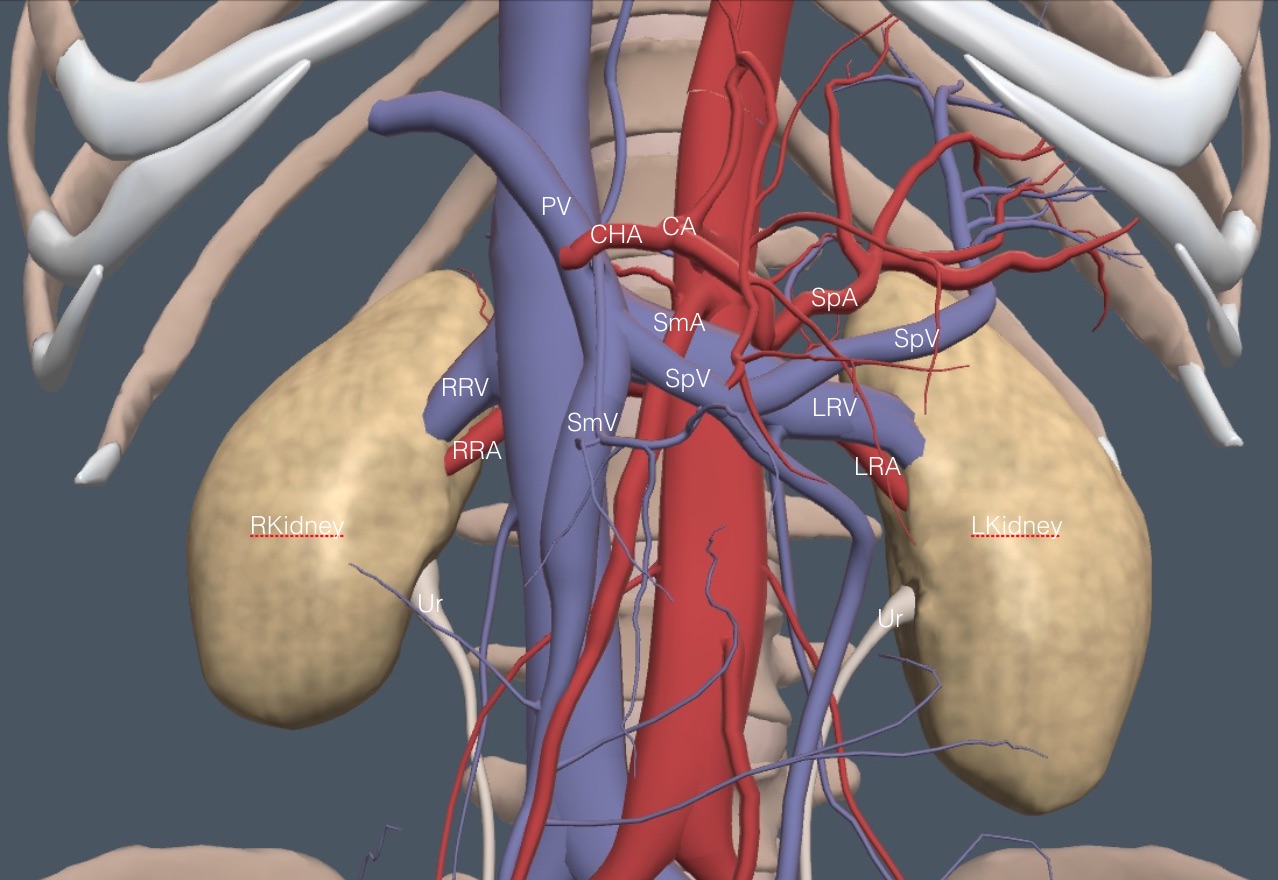

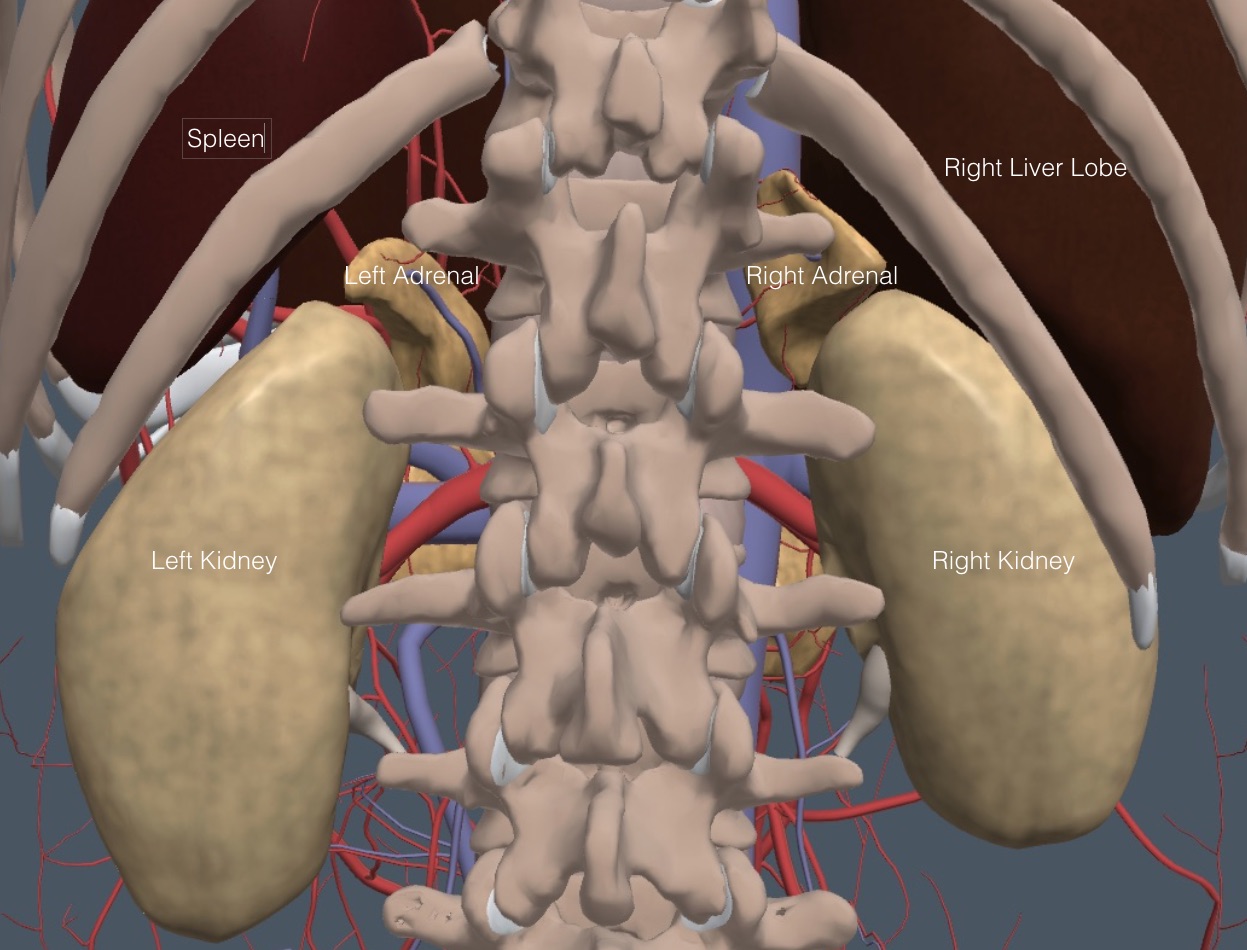

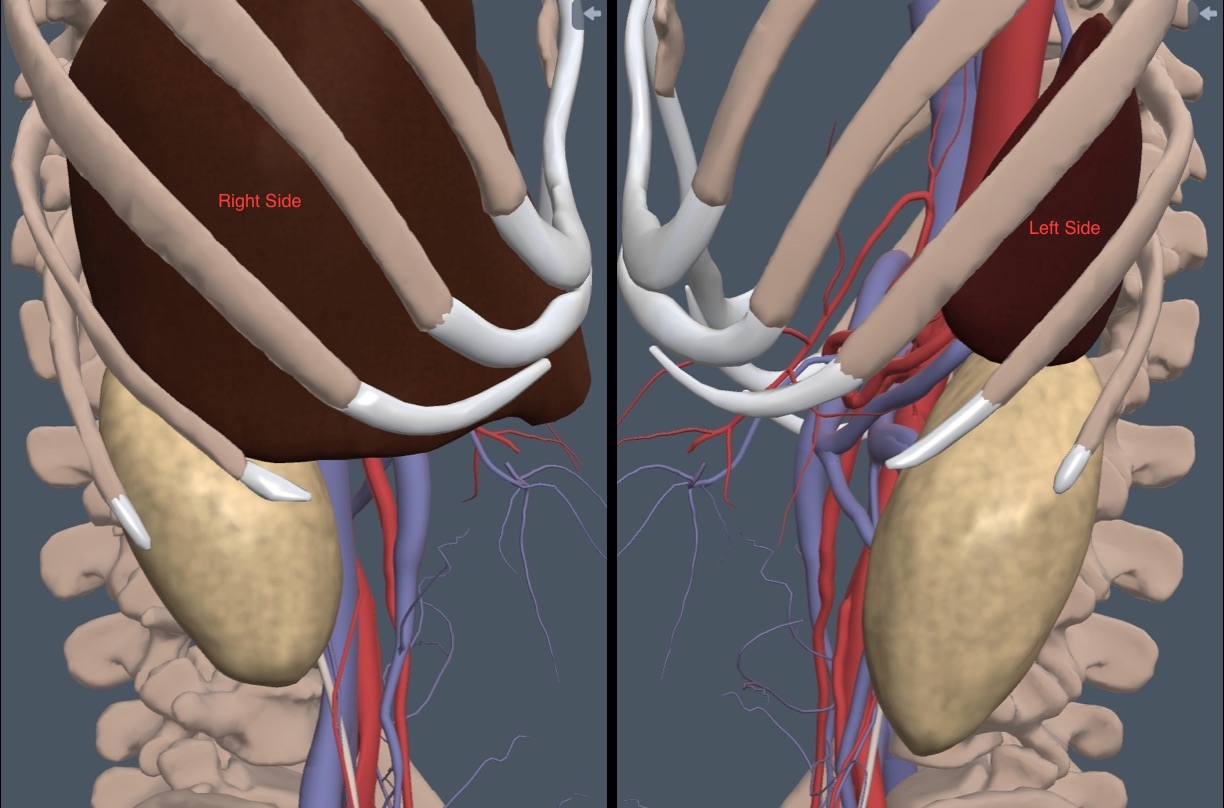

The bean-shaped kidneys lie in the retroperitoneum behind all other abdominal organs. The cephalad poles are rotated medial and posteriorly. The left kidney may lie more cephalad than the right kidney. The vessels in this region were covered in a previous chapter but are labeled again in this frontal anatomy diagram.

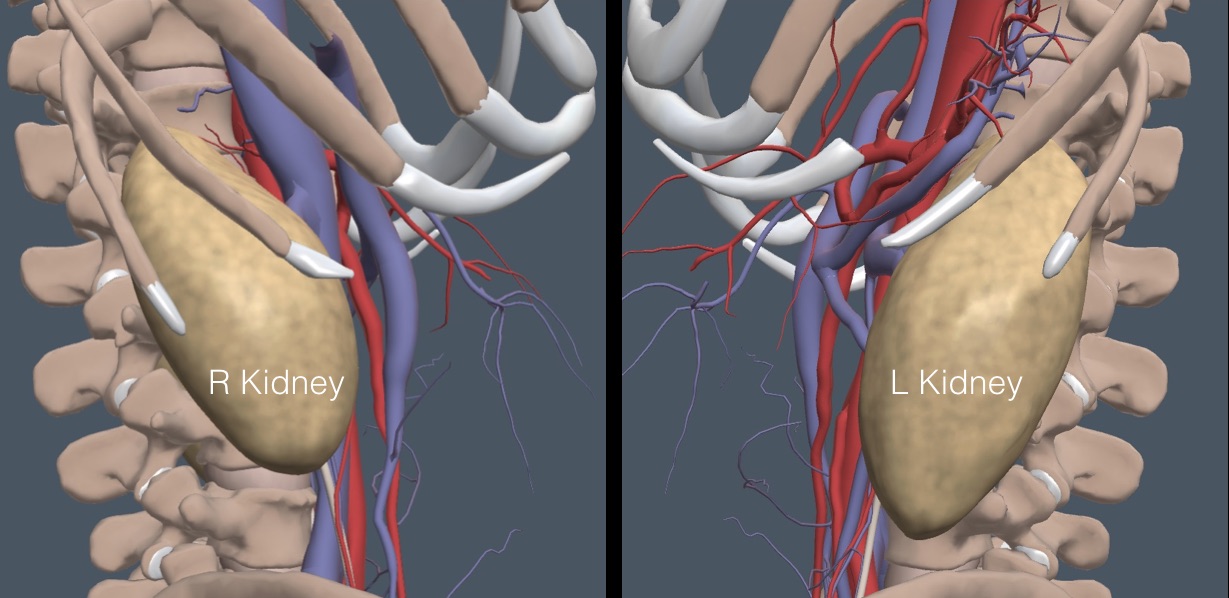

The following lateral view shows that intercostal spaces at about the mid-clavicular line give a long-axis, coronal view of the kidneys. Ribs cover the upper third of each kidney.

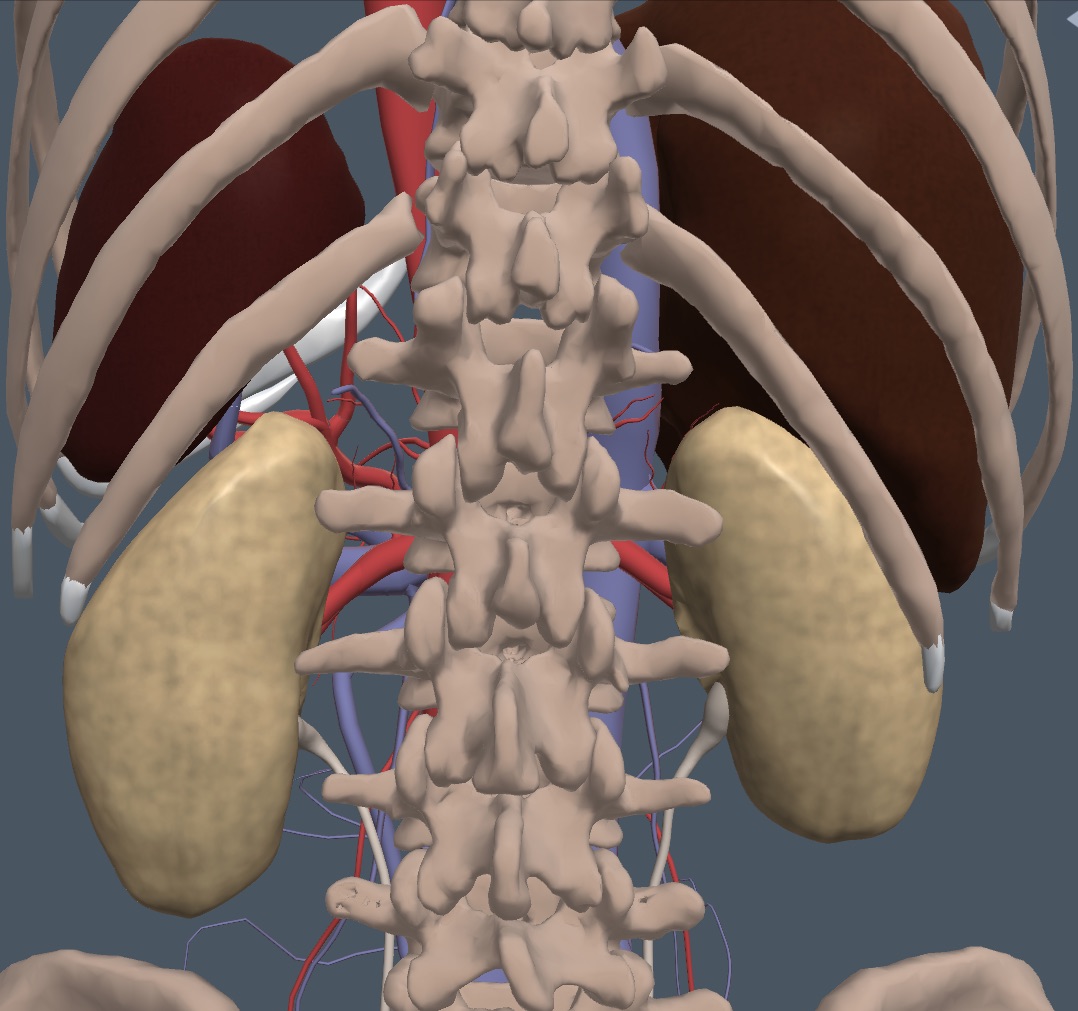

The liver is cephalad and anterior to the right kidney, and the spleen is cephalad and anterior to the left kidney, as shown in the following image.

The psoas muscles are medial to the kidneys, and the quadratus lumborum muscles and adipose tissue are posterior. During respiration, the kidneys move up and down on these muscles.

The psoas muscles are medial to the kidneys, and the quadratus lumborum muscles and adipose tissue are posterior. During respiration, the kidneys move up and down on these muscles.

KIDNEY MICRO ANATOMY:

A section through a normal kidney shows three microscopic areas. The central area, the renal sinus, consists of the calyces, fatty tissue, and renal pelvis. The next zone out is the renal medulla, which comprises the medullary pyramids, separated by renal columns. The most external area is the renal cortex. The renal columns are portions of the cortex anchoring to the renal pelvis, so the tissue is identical to cortical tissue.

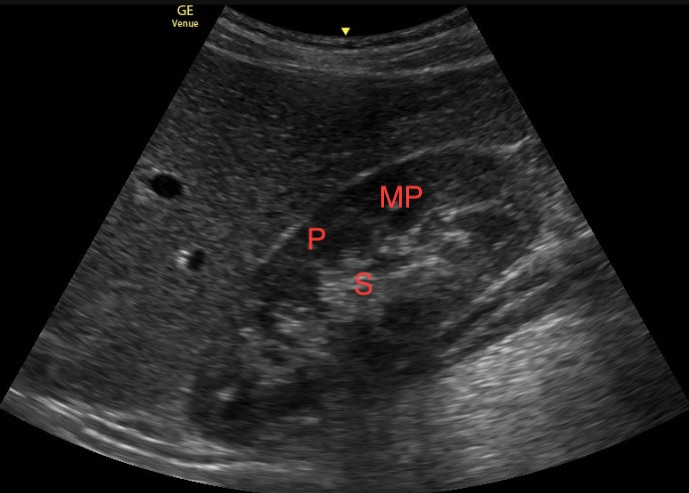

With IMBUS, the renal sinus is a single hyperechoic area, except for whatever anechoic urine may be present. The medulla and renal cortex form a more hypoechoic peripheral area called the parenchyma. When accumulating urine, the medullary pyramids are seen as small, anechoic areas in the inner parenchyma. Here is a still image of a normal kidney with the areas labeled P for parenchyma, S for renal sinus, and MP for medullary pyramid.

IMAGING THE KIDNEYS:

The lateral decubitus patient position is standard for kidney ultrasound, but if this produces suboptimal images, having the patient stand can improve the view.

The kidneys move with respiration, so make sure patients halt their respiration for a short while whenever the best view of a kidney is found. Subtle kidney abnormalities may be missed if the kidneys are constantly in motion.

CORONAL VIEW

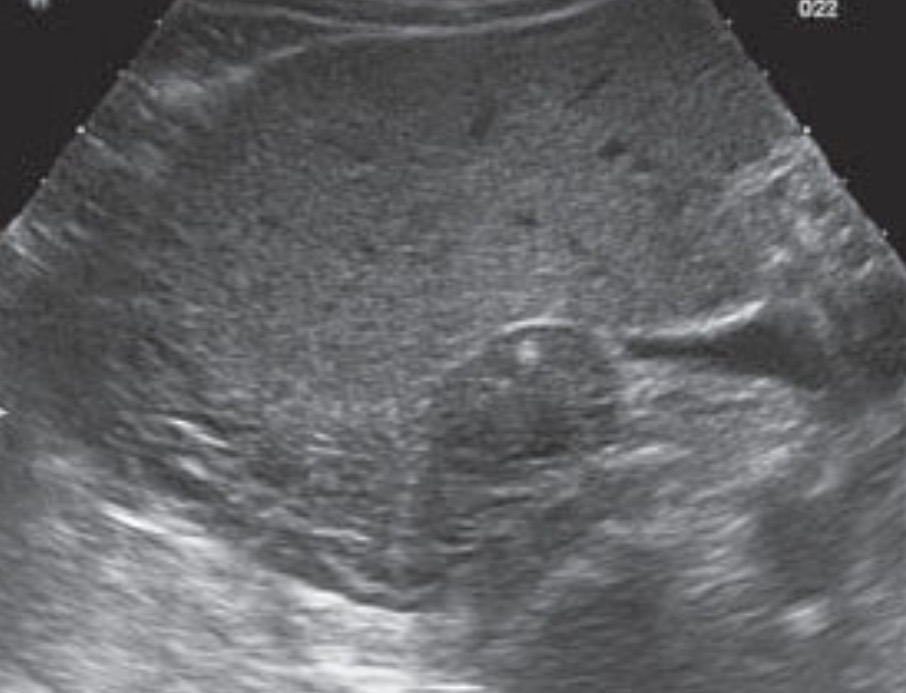

With either left or right lateral decubitus patient positions, find an intercostal space in about the midaxillary line and place the probe with the indicator toward the cephalad pole of the kidney and the lower edge of the probe at the costal margin. The interspace is usually tilted posteriorly, as the kidney should be. Slide caudad if the lung is seen. If the liver or spleen is seen, move posterior an intercostal space. This mostly coronal view of the kidney is usually better for finding hilar structures like the ureter on the medial side of the kidney (the side farthest from the probe) because they are parallel to the beam. Rotate the probe to get the best long-axis view. Sometimes, the rib shadows prevent a clear view of the whole kidney. Here is a normal right kidney with a breath hold.

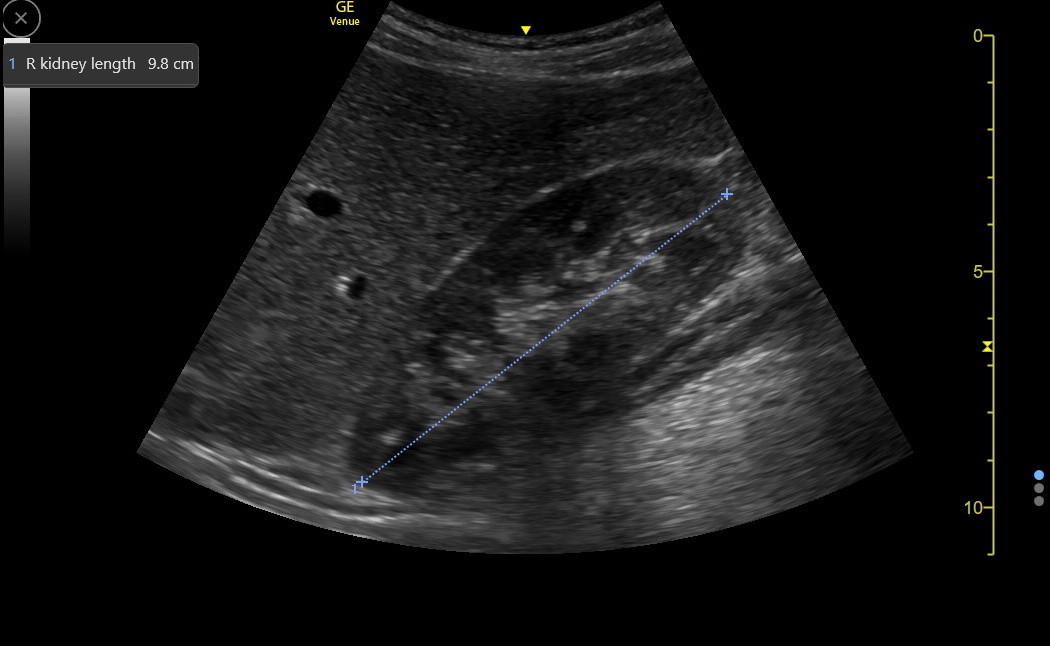

The renal sinus should be hyperechoic, and the parenchyma should be hypoechoic with an optimized long-axis view. Freeze and measure the longitudinal dimension of the kidney as in the following image.

Normal adult kidneys vary with patient height, ranging from 10 to 12 cm in long axis. There is gradual shrinkage of the kidney parenchyma as many people age or develop various chronic diseases. Since the kidney sinus region doesn’t shrink, the parenchymal thinning will be detected as a decreased kidney length. Parenchyma can also become more hyperechoic with some diseases.

After measuring the kidney, fan anterior/posterior through it to see the hilum on the medial side, where the ureter and vessels enter and leave. Use Color to identify the hilar vessels.

ABNORMAL KIDNEY FINDINGS

Large kidneys: occur in acute nephritis and occasionally in early diabetic nephropathy and amyloid renal disease. The parenchyma is often more hyperechoic in these conditions, but be sure the gain is set correctly. Here is an image from a patient with acute SLE nephritis showing increased parenchyma echogenicity. The kidney measured more than 12 cm in length.

Small kidneys: indicate chronic intrinsic renal disease, chronic infection, or renal artery stenosis. If a small kidney is congenital, the contralateral kidney is usually enlarged. The following is from a screening exam on an older woman without a known cause for kidney disease. The right kidney measured 6 cm, while the left was 9 cm.

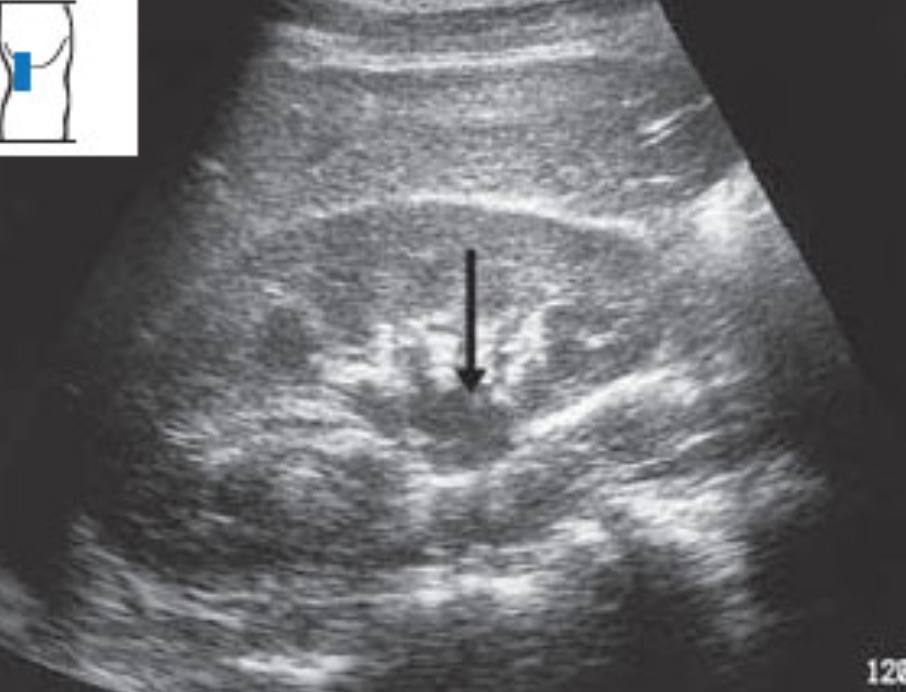

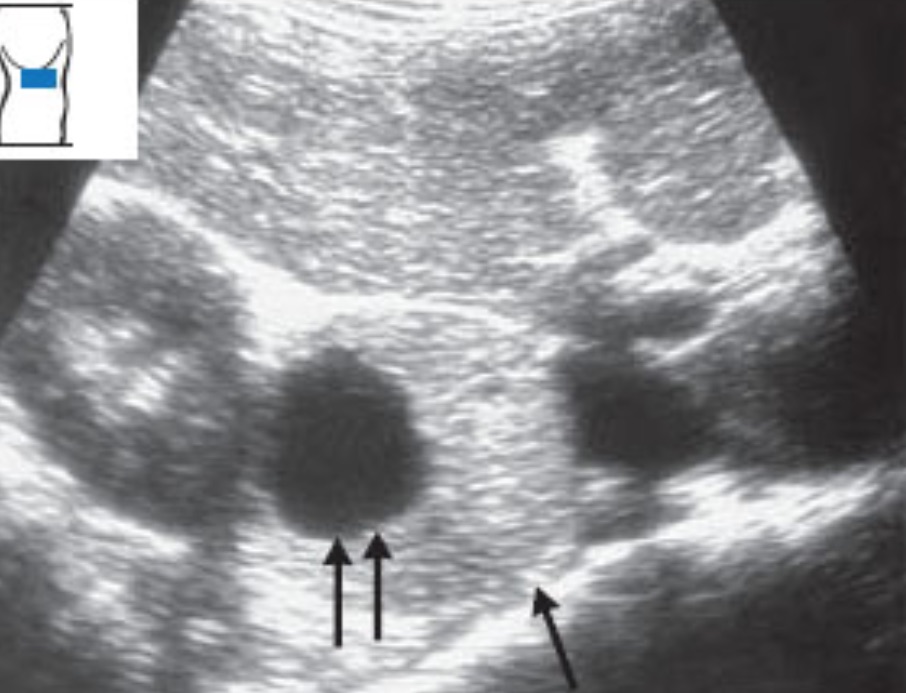

Horseshoe kidney: This is a congenital malformation in which the lower poles of both kidneys are joined together by a parenchymal bridge that crosses up and over the aorta as a hypoechoic structure. The lower kidney poles don’t taper normally and look indistinct in the standard views. Here is a clinic patient with the hypoechoic parenchymal bridge crossing the aorta and connecting to the left kidney.

A horseshoe kidney causes no kidney trouble but can be associated with other genitourinary abnormalities, so it is worth noting.

Kidney stones: Stones in the kidney appear in the renal pelvis or calyces and can be difficult to see because this area is already hyperechoic, so the stone does not stand out. Only an acoustic shadow from the stone may distinguish it. To accentuate a shadow, reduce the gain somewhat. Here is a kidney with several stones in the sinus that have shadows.

Color/Power Doppler will cause some kidney stones to light up and “twinkle,” even when there is no shadow, but we do not have a clip of this to show in the kidney. The twinkling of a stone at the end of a ureter is demonstrated in the Bladder/Pelvis chapter. Reports indicate that 80% of renal stones exhibit twinkling artifacts. Machine settings determine the amount of twinkling, and having the focus position posterior to most of the renal sinus can enhance the twinkling. However, twinkling is not specific to kidney stones, as demonstrated in the following clip with prominent twinkling of a calcified lateral hip mass that turned out to be heterotopic ossification. Notice the dense posterior shadow. Twinkling probably indicates an irregular-surfaced calcification seen in different organs from various causes.

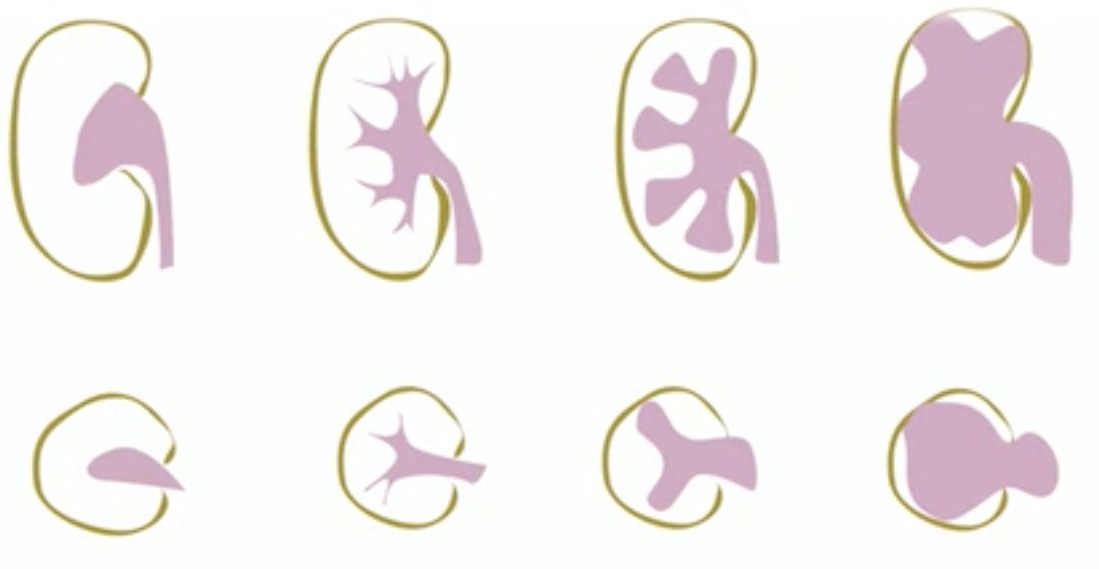

Hydronephrosis: Basic hydronephrosis was covered during IMBUS-Core, but here are more details about some aspects. The following diagram depicts the progressive severity of hydronephrosis.

In mild hydronephrosis, the ureter and renal pelvis first dilate with urine. The calyces and medullary pyramids are still normal in size. The ureter comes from the medially located hilum, posterior to the vessels. It runs posterior to the edge of the kidney and then caudad toward the pelvis. Identify the hilar vessels of each kidney with Color/Power Doppler, followed by posterior fanning to see an isolated hydroureter. If a dilated ureter cannot be found, be skeptical of diagnosing hydronephrosis. Here is a clip of a patient with early obstruction from a ureteral stone producing mild dilation of the distal renal pelvis and the proximal ureter.

The dilated ureter is essential because normal adults can show some urine in the renal pelvis when actively forming urine, but the ureter is never dilated. Here is a still image from a normal adult with good urine in the renal pelvis and medullary pyramids but no ureteral dilation.

Ureteral dilation is also essential for differentiating a congenital condition called “ampullary pelvis,” in which the renal pelvis is dilated, but the calyces and ureter are normal. Here is an example.

This would be a difficult call, but seeing no dilation of medullary pyramids and no dilation of the ureter should make us skeptical of hydronephrosis. A decision must be made with each patient about whether it is better to over-call or under-call mild hydronephrosis. Uncertainty about early hydronephrosis might lead to confirmatory CT or formal ultrasound in some patients. However, a patient can sometimes drink 250-500 mL of fluid over a reasonably short period and return a few hours after to be re-examined. The patient could also return the following day to look for progression of hydronephrosis. The next chapter will discuss ureteral bladder jets to aid decision-making regarding possible early hydronephrosis.

As hydronephrosis increases, the major calyces, the minor calyces, and the medullary pyramids eventually dilate and finally begin to compress the renal parenchyma. Moderate hydronephrosis becomes a more straightforward diagnosis, but ensure the ureter is dilated. Here is moderate hydronephrosis with an easily seen dilated ureter.

Severe hydronephrosis is usually easy to identify, as in the following clip, but never forget the dilated ureter (not well seen in this clip) to be sure that this isn’t severe polycystic kidney disease (polycystic disease should be bilateral) or multiple and large parapelvic cysts (see below).

A warning about left-sided hydronephrosis: Rarely, a large aortic aneurysm can obstruct the left ureter, so the aorta should be imaged in middle-aged or elderly patients with left-sided hydroureter or hydronephrosis.

Summary IMBUS clinic approach to possible kidney stones: Kidney stones < 5 mm in size cause symptoms but rarely obstruct a ureter, don’t seem to benefit from tamsulosin therapy, and don’t need instrumentation. Thus, a patient with moderate symptoms consistent with a kidney stone but normal kidneys and ureters by IMBUS can be treated with simple pain medication and hydration at home while observing for stone passage and symptom relief, especially if a bladder jet is seen on the culprit side. These patients could have early clinic follow-up and would usually not need a CT scan. Conversely, a patient with symptoms suggesting a ureteral stone and ≥ mild hydroureter and hydronephrosis should proceed immediately to CT because the location and size of the stone dictate how quickly urology might need to be involved. Patients with severe and more ill-defined symptoms often still need CT after normal kidney IMBUS because they could have other serious diseases. However, the CT scan would usually be done with contrast to best diagnose the other conditions.

Renal cysts: Pure, simple cysts can be single or multiple, are always benign, and are usually clinically silent, although bleeding and acute pain rarely occur. However, make sure there are no complex features. There should be posterior acoustic enhancement and often lateral wall shadows. Simple cysts should be round or oval, without internal echoes, and have a thin, sharp posterior wall. This next clinic patient had several simple cysts in the left kidney, but on the right side, there was a dominant cyst that was not quite round, distorted the kidney a bit, and seemed to have some solid elements. The physicians appropriately obtained CT imaging, and a renal tumor extending into the renal vein was found. It was resected for possible cure and identified as a renal cell carcinoma.

Simple cysts can bulge off a kidney (pararenal), be in the cortex (cortical), or be in the renal medullary area (parapelvic). Here is a single, simple pararenal cyst off the lower pole of a kidney. The cyst is round with no internal echoes, slight posterior acoustic enhancement, and a lateral wall shadow.

Here is a clip of a parapelvic cyst extending out into the cortex. There is strong posterior acoustic enhancement.

Cysts can be very large, but as they become multiple and bilateral, the worry is about polycystic kidney disease, and confirmatory imaging is needed (either contrast-enhanced CT or MR). The following clinic patient had multiple large cysts in both kidneys and had a mother who had been diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease.

Renal masses: This is a complex topic. There is no information about screening for renal tumors with ultrasound. Most renal tumors are considered dangerous and finding them early would usually be a benefit. In asymptomatic patients, such tumors are found incidentally. There is a normal renal variant with a hypertrophied renal column that makes physicians worry about cancer. However, the tissue is isoechoic with the rest of the renal parenchyma, which would rarely be the case with a renal neoplasm.

The American College of Radiology guidelines state that a CT-identified solid renal mass less than 1 cm in greatest diameter should not be biopsied but followed at 3-6-month intervals until it is over 1 cm. Since solid renal masses are rare in our clinic and our detection limit is probably close to 1 cm, any solid lesion should get confirmation by CT or MR.

Hypernephroma/renal cell carcinoma is the greatest fear. Such tumors can be hyperechoic or hypoechoic, are inhomogeneous, can cause a bulge in the renal outline, and are often scalloped along the border. Here is a left kidney in which a hypoechoic bulge greater than 1 cm was identified and was diagnosed as a clear cell renal carcinoma.

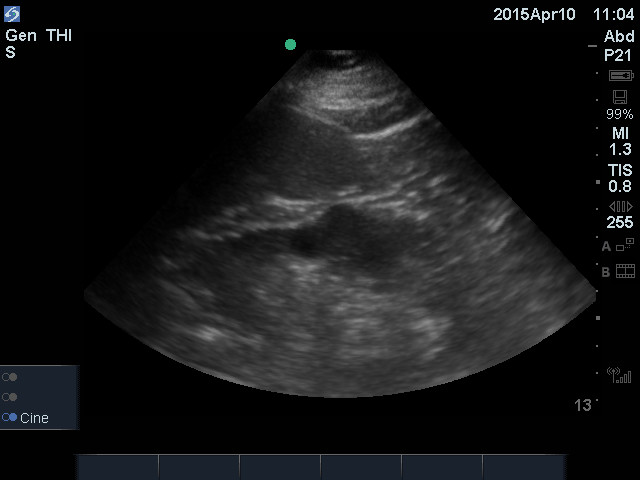

Unfortunately, the left kidney may infrequently have a benign malformation called a “dromedary hump,” which is a little bulge opposite the border of the spleen, as in the following image. This is normal kidney tissue, so it should be isoechoic with the rest of the parenchyma. The decision to get confirmatory CT or MR can be difficult.

Here is a clip showing a more extensive, bulging lesion with a mixture of hyperechoic and hypoechoic elements. This was also a renal cell carcinoma.

Angiomyolipomas are hyperechoic parenchymal lesions reminiscent of the “snowball” angiomas in the liver and spleen. These can be distinctive enough to be diagnosed as benign and not pursued, but a confirmatory formal US would be obtained when a lesion was not distinctly hyperechoic.

ADRENAL GLAND MACRO ANATOMY

Imaging normal adrenal glands may be difficult, but a large adrenal mass may be seen incidentally during a kidney exam.

Normal adrenal glands are 3-7 cm long and lie cephalad and medial to the kidneys, as in the following view from the back of a patient.

The right adrenal lies posterior to the liver and lateral to the IVC. The left adrenal is posterior to the spleen and lateral to the aorta.

IMAGING ADRENAL GLANDS

With the kidneys in the long-axis, the adrenal glands will be just cephalad of the kidney and a bit medial. The right adrenal gland will abut the liver and be lateral to the IVC. The left adrenal gland will be against the spleen and lateral to the aorta.

The best view of the adrenal glands will be intercostal through the liver and spleen, with long-axis kidneys. The cephalad pole of the kidney must be seen, and then a very slight medial fan should bring in the adrenal glands. The following is a normal right adrenal gland showing as a triangular-shaped, slightly hyperechoic structure between the superior pole of the kidney and the liver.

Next is a normal left adrenal region in the patient above with the parapelvic cyst.

ADRENAL GLAND PATHOLOGY

An IMBUS exam can probably only visualize an adrenal mass larger than 1 cm; at this point, malignancy and hormones are the issues. The malignancy pathway is determined by a patient’s history of cancer and the CT/MR size and appearance. Thus, the IMBUS rule must be that lesions greater than 1 cm would go to CT or MR (or PET/CT in a patient with a history of cancer).

Adrenal hemorrhage is an acute medical condition that could be visualized with IMBUS. Unilateral hemorrhage is often not symptomatic, but bilateral hemorrhage can lead to adrenal crisis. An early hematoma is solid with diffuse or heterogeneous echogenicity. Later, the mass becomes mixed, cystic, and then solid. Calcification can occur as early as several weeks.

Adrenal masses larger than 1 cm are recommended to be screened for hormone excess. We will not detail these steps.

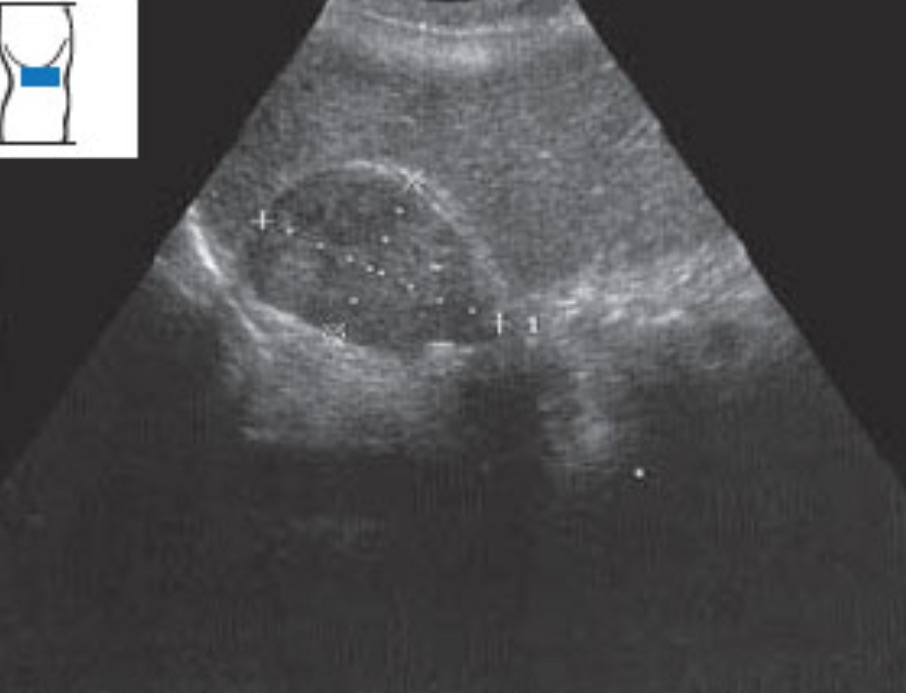

Adrenal cyst: Adrenal cysts can be any size. Larger cysts may reduce the adrenal gland's function. Here, a large adrenal cyst is pushing up against a kidney.

Adenomas: Solid lesions large enough for IMBUS viewing could be benign, malignant, or functional. An extensive registry of adrenal adenomas found that even “non-functioning” adenomas had a long-term increased incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events, suggesting that some of these adenomas may have an adverse, low-level function. Here is a reasonably large, non-functioning right adrenal adenoma.

Pheochromocytoma: Pheochromocytomas can be small to large. IMBUS would not detect small ones, but this is an image of a large pheochromocytoma with cystic and solid parts.

Metastasis: Adrenal metastasis is classic in small-cell lung cancer but can also occur in other tumors. IMBUS can’t differentiate a metastasis from other benign or malignant lesions. Here is a left adrenal metastasis from small cell lung cancer that was pushing up into the spleen.

Primary carcinoma: Adrenal carcinoma is unusual and may or may not secrete hormones. Patients may only have weight loss and anorexia. Here is an example.