Lungs

In the outpatient setting, the spectrum of pulmonary disease and characteristics of the ultrasound exam are notably different than that seen in the acute inpatient and intensive care unit settings.

The essential findings with lung ultrasound are VPPI (lung) sliding, B-lines, consolidation, and effusion. Different probes and settings are needed to optimize these findings because sliding and B-lines are artifacts while consolidation and effusion are real tissue/fluid (Matthias et al., J of Ultrasound Med 2020:9999:1-8). We use two probes and three presets with Venue to cover the range of patient presentations. These will be covered in more detail at the end of this chapter.

The spectrum and severity of pulmonary disease differ in the primary care clinic from that in the emergency department or critical care unit where lung ultrasound was initially developed. Clinic patients are usually sub-acutely or chronically ill with cough, mild shortness of breath, or localized chest discomfort. These patients need a careful but efficient evaluation of all lung lobes.

Clinic patients can always be examined upright, which has two advantages. First, the lungs are more fully expanded in all but the most obese patients. Second, pleural effusions are better detected and quantified in this position. The standing position is more efficient and ergonomically better for the physician and is our standard for patients who can stand for 10 minutes.

Rather than the phased array, the curvilinear probe is used in a fully intercostal position with Venue. More VPPI can be seen with each probe placement, allowing a quicker exam. The modestly higher frequency of the curvilinear probe is an additional advantage.

The intercostal spaces are mostly horizontal at the upper chest but become more obliquely angled in the lower chest, so the probe needs to be subtly rotated to stay intercostal as it is moved on the chest. Rib shadows shouldn’t be seen.

The clinic physicians using Venue and the curvilinear probe begin with the posterior chest, where abnormalities are more frequent. Except for massive patients, a first vertical line of ultrasound gel is applied to the right chest from the upper chest to the costal margin, in between the medial scapula and the paraspinous muscles. A second line is used from the lower edge of the middle of the scapula to the costal margin. A pass along these two lines with the curvilinear probe usually covers the posterior lung. The probe should stop moving briefly in each intercostal space while the patient breathes.

After a posterior chest side is complete, it is cleared of gel, and the patient is turned to position the lateral chest of that side in a good exam position. A mid-axillary line of gel is applied for a single probe pass. The gel is wiped off, the patient is turned back, and the process is repeated for the other side of the chest. Finally, the patient is turned for the anterior exam, and one midclavicular line of gel with one curvilinear probe pass is usually enough on each side.

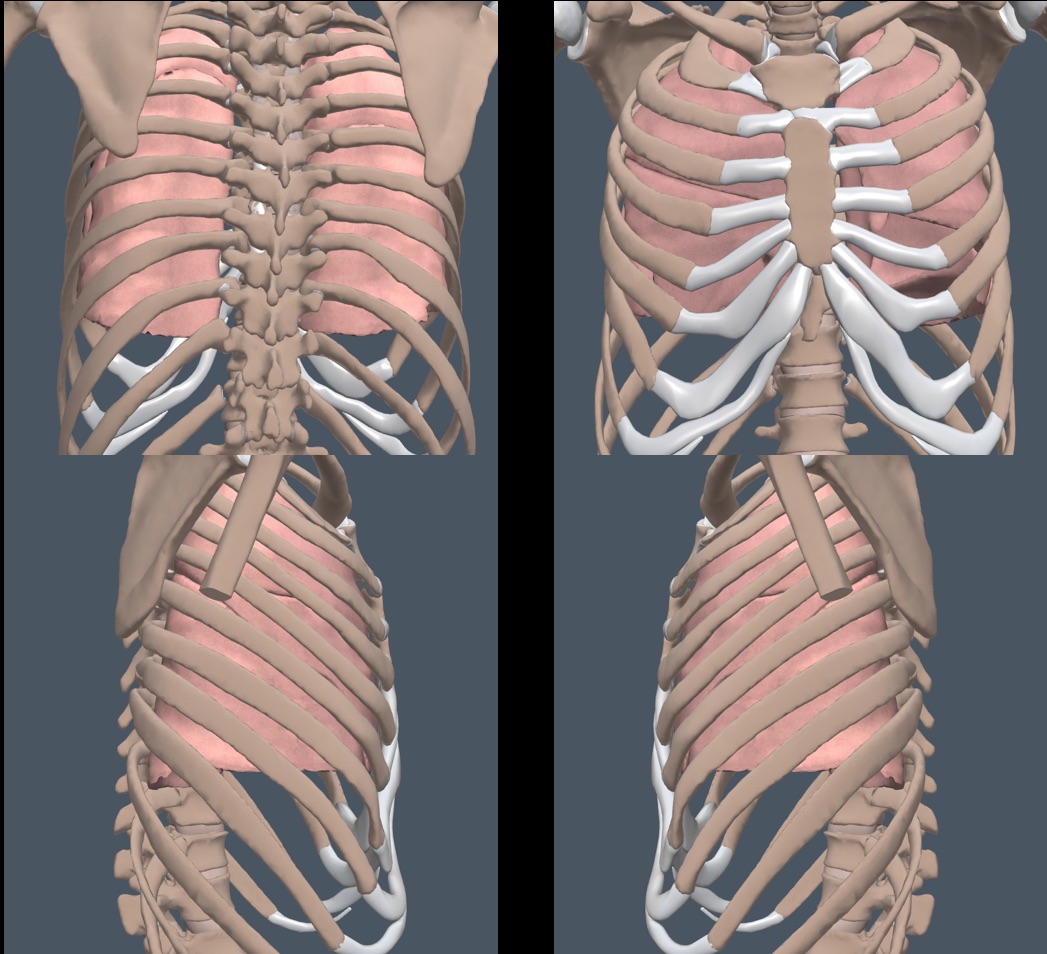

Below is an image that shows the approximate surface projections of the main lobes of the lung. We document localized findings with “lobe terminology” to correlate with radiology reports and better communicate with non-IMBUS physicians.

PNEUMOTHORAX AND VPPI (LUNG) SLIDING: (Linear probe; PNEUMO preset)

We use this exam infrequently in clinic, usually for a patient who has fallen and broken a rib. The supine patient position is better for a suspected pneumothorax because free intrapleural air moves to the easier-to-examine third or fourth anterior intercostal spaces. VPPI sliding in these spaces excludes pneumothorax in the area, so the exam should be optimized for sliding.

We use the linear probe and a preset called PNEUMO with RES frequency, 6 cm depth, a focus position on the VPPI, and ARTIFACT-ENHANCING settings. In B-mode, “ants marching” on the VPPI is sought, as shown in the following clip.

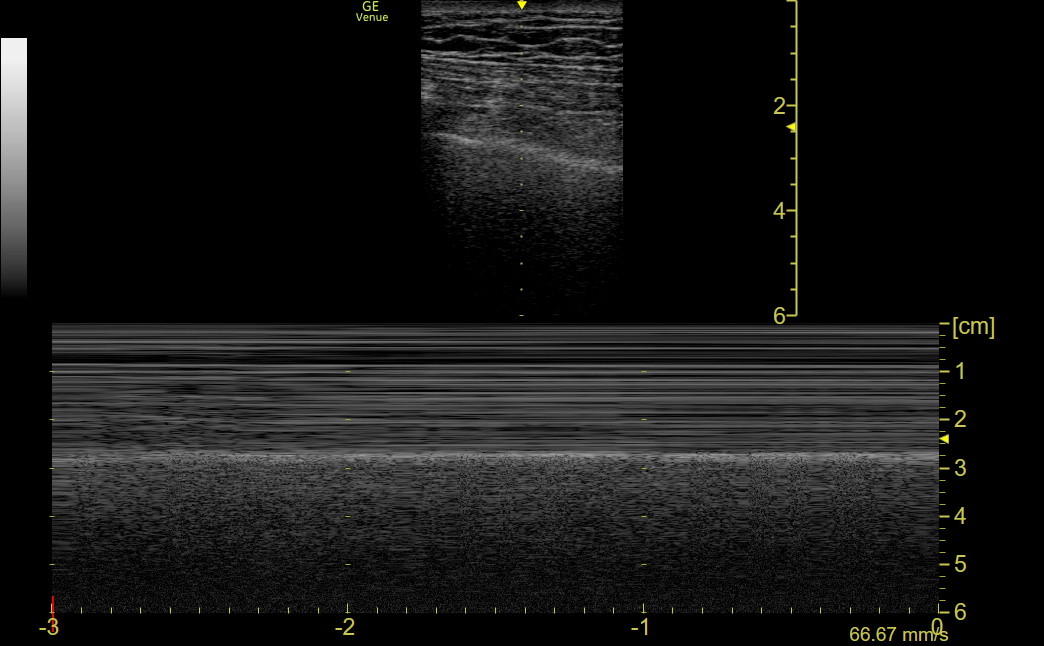

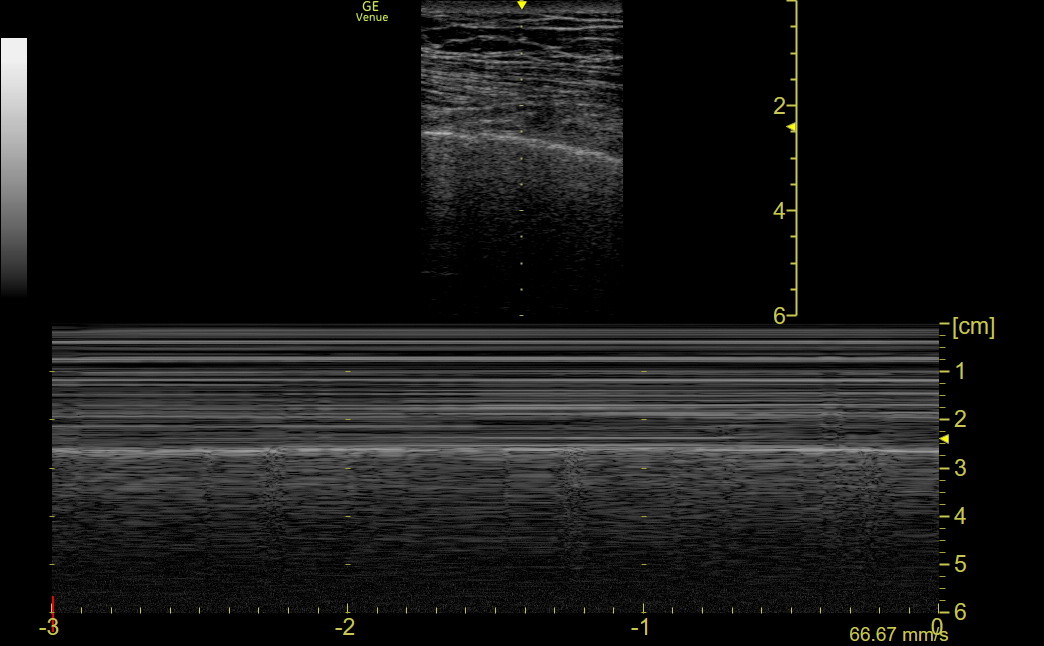

M-mode has a higher frame rate than B-mode, so it is better at detecting sliding in equivocal cases. The PNEUMO preset gives excellent M-mode tracings that identify a normal “seashore” pattern in a breathing patient with an intact VPPI. The following normal tracing shows the minimally moving soft tissue at the top (the sea with lines of waves) next to the grainy beach, created by the motion of the VPPI.

In contrast, a pneumothorax patient has a “barcode” pattern because the VPPI is not moving. The whole tracing looks like the sea in the above tracing. If a patient has an intact VPPI (no pneumothorax) but a non-ventilated lung (e.g., mucous plugging, obstructing tumor, or a misplaced endotracheal tube), B-mode sliding will be absent, suggesting pneumothorax. However, before getting the chest tube tray, apply M-mode. The pattern will be predominantly barcode, but pneumothorax can still be excluded if a “lung pulse” is seen in the barcode. We don’t have a patient example, but the lung pulse can be seen in normal people, as in the following image from a healthy subject who held his breath.

The lung pulse is created by cardiac motion transmitted through a non-ventilated lung with an intact VPPI. You can feel the carotid with your left hand while the M-mode is running to confirm that the brief motion in the tracing corresponds with the heartbeat.

If B-mode sliding is absent and M-mode shows a bar code pattern without a lung pulse, pneumothorax is nearly certain, and a “lung point” should be sought to assess the degree of pneumothorax. Move the probe laterally in the intercostal space, searching for the line where sliding, the seashore sign, and the lung pulse resume. A lung point may be very posterior or even absent with a large pneumothorax.

VERTICAL LINE ARTIFACTS

Three vertical lines are essential to recognize when device settings are optimized for artifacts (Lee et al., Med Ultrason 20:379-384 2018).

Lung comets are a reverberation artifact seen almost only with the higher frequency linear probe. They are not associated with disease, arise at the VPPI, move with intact sliding, and fade quickly, so they are only 1-2 cm long (too short to be confused with B-lines). The following non-Venue clip shows a lung comet.

B-lines are a “ring down” artifact produced by a specific arrangement of air and fluid at an intact VPPI. Depending on the device and settings, B-lines can appear continuous or as a stack of successive short horizontal bands. They can look like a ray of light and go to the bottom of the screen without fading. B-lines cover up A-lines and move with sliding. Sparse B-lines may be seen at the lung bases in young, healthy people, and the number of B-lines and the number of chest areas positive for B-lines increase with age without necessarily indicating pathology. The following Venue clip shows diffusely increased B-lines in a clinic patient with decompensated HFrEF.

Vertical lines originating below consolidation or atelectatic lung are usually called B-lines, but they are technically different and don’t necessarily indicate an interstitial syndrome in the area.

Z-lines are regularly seen, particularly in thin individuals, and have been confused with B-lines. However, they do not originate at the VPPI, do not move with sliding, and blend in with, rather than covering A-lines. Z-lines are weaker in appearance and, in contrast to B-lines, fade with increasing depth. Here is a clip with the linear probe and the PNEUMO preset showing 2-3 stationary Z-lines.

DYSPNEA AND B-LINES: (Curvilinear probe; LUNGS_BLINES preset)

When a clinic patient without trauma has acute or subacute dyspnea as the dominant symptom, an upright exam with the curvilinear probe should be performed. When these patients have clues that suggest infection or PE, the LUNGS_CONSOL preset described in the next section should be used first.

Patients with clues more consistent with heart failure, obstructive lung disease, or interstitial lung disease need an exam optimized for B-lines. The LUNGS_BLINES preset has a depth of 12 cm, focus position at the VPPI, and ARTIFACT-ENHANCING settings.

The B-line count should be the maximum number in an ultrasound frame, not the estimated cumulative number seen during respiratory motion. When potential B-lines are suspected with Venue, we freeze the screen, scroll back with a finger swipe, and count the frame with the most B-lines. B-lines wide at the VPPI are considered fused and should be counted as more than one. With a full intercostal curvilinear probe view, a B-line count greater than 6 is abnormal. The following frame shows 4 B-lines in a healthy older patient's right lower lobe.

INFECTION/PE and CONSOLIDATION/EFFUSION: (Curvilinear probe; LUNGS_CONSOL preset)

Effusions and consolidation are the most important findings when infection or PE is suspected. The LUNGS_CONSOL preset has a depth of 8 cm, a focus position on the VPPI, and parameters that SUPPRESS artifacts and ENHANCE tissue definition. The depth can be increased when large effusions or consolidations are seen. B-lines may be seen with this preset, but many are suppressed, so the count is falsely low. If we suspect B-lines, we quickly switch the preset to LUNGS_BLINES.

Free-flowing pleural effusions are best seen with an upright patient and a parasagittal probe position at the medial and posterior lung border. The following clip shows a small pleural effusion in this location (the anechoic triangle at the top with expiration).

Quantifying pleural effusions: Several formulas have been derived to quantify a pleural effusion in mL, but a 200 mL effusion means something different in patients of various sizes. It is better to make a semi-quantitative estimate of relative pleural effusion size based on the progression of effusions in most patients. The following diagram depicts a parasagittal probe position at the medial, posterior lung in an upright patient. The ordered numbers indicate the progression of effusion size and the typical growing sequence of the associated compressive atelectasis in the lower lobe.

A patient with effusion/atelectasis only in zone 1 would be mild; as each zone is added, the size increases from moderate to large. A patient with unaerated lung in areas 6 & 8 before developing atelectasis in regions 3 & 4 should raise suspicion for an additional process beyond simple compressive atelectasis from effusion.

Here is the schematic of the effusion/atelectasis progression as it would appear on the ultrasound screen with the same posterior parasagittal probe position in an upright patient. The patient example following represents a "moderate" size pleural effusion.

The earliest ultrasound sign of infection/inflammation should be thickening of the VPPI with a “lumpy, bumpy” appearance. As sub-pleural consolidation progresses, small hypoechoic spaces appear in the VPPI, and any vertical lines begin below these hypoechoic areas. The hypoechoic areas can be small, moderate, or large. Here is an example of a small sub-pleural consolidation with a wide vertical line beginning below the consolidation.

Viral pneumonia should have diffuse small subpleural consolidations, sometimes with skip areas, with or without vertical lines below the consolidations. With bacterial pneumonia, the process is almost always focal. The dividing line between extensive focal sub-pleural consolidation and full consolidation is a judgment call that depends on how deep the process extends below the VPPI and the presence of air bronchograms. It is not necessary to see B-lines with bacterial pneumonia.

Moderate-sized hypoechoic gaps, with or without B-lines, were described in a series of pulmonary embolism patients, and larger gaps were seen with lung metastases. This finding is probably only 40-50% sensitive for PE, but it can be a good clue in the right patient. We saw a clinic patient four days after an uncomplicated lumbar micro-discectomy. Bilateral, migratory chest and shoulder pain had been present without dyspnea. Early on, there was a sharp inspiratory discomfort in the back, but the pain was not pleuritic at the time of the clinic visit and was thought to be from the surgical site. The PCP thought PE was a low probability, but the IMBUS exam showed multiple moderate-sized sub-pleural lower lobe consolidations. CT showed multiple, small, bilateral PEs. Here is the Venue clip obtained with a modestly different preset from our current LUNGS_CONSOL.

Complete consolidation with air bronchograms is unusual in the clinic because most patients with this finding are sick enough to have gone to the ED. The following patient was seen in our clinic after many days of home illness and was described by her physician as “one day away from the ED.” This clip from the left lateral chest shows some dense consolidation, a few dynamic air bronchograms, and a shred line. As noted above, the vertical lines below the shred line do not necessarily indicate an interstitial pattern below the consolidation. This was not yet a complete lobar consolidation, and the patient was successfully treated as an outpatient.

Pneumonia rarely does not extend to the visceral pleura (necessary to produce ultrasound-visible findings such as subpleural consolidation). Thus, a moderately ill patient with symptoms that support pneumonia but who has a negative lung IMBUS exam may need a CT scan for an accurate diagnosis. Empiric antibiotics may sometimes be justified in such a patient.