Venous Thromboembolism

IMBUS of peripheral veins can achieve faster diagnoses, reduced cost, and improved patient satisfaction, but only with detailed knowledge of venous anatomy and good experience with the technique.

PULMONARY EMBOLISM (PE)

Clinic patients suspected of PE enter an urgent diagnostic pathway because early therapy is needed for this disease. A normal d-dimer (dD) lowers the chance of PE to a very low percentage in patients with a low pre-test probability. However, because dD isn’t immediately available in most clinics, these patients have often received CT PE with its radiation, IV contrast, inconvenience, and expense. Multi-organ POCUS (heart, lungs, and veins) can improve the speed and accuracy of diagnosis (Nazarian et al., Chest, Oct. 2013) and avoid many CT PE studies.

Cardiac IMBUS can detect clinically meaningful right heart dysfunction with a sensitivity equivalent to formal cardiac ultrasound, and this finding shifts a patient to an emergent admission path. (see the Advanced Right Heart Disease chapter for more details about the heart in acute PE). A CT PE may still be needed in such patients unless a major venous clot is also seen, and then the patient might be treated immediately upon admission. Cardiac IMBUS could find another reason for a patient’s presentation, such as heart failure, and the CT PE study would not be needed.

Lung IMBUS can find alternative diagnoses such as consolidation pneumonia, large pleural effusion, or diffuse interstitial edema. The 2013 report noted that patients with PE can have localized, modest-sized, wedge-shaped, sub-pleural consolidations, most commonly in the posterior and caudal lungs. This finding has a high positive likelihood ratio for PE. However, sub-pleural consolidation can be seen in infectious and metastatic disease, so a patient’s other clinical factors are essential for diagnostic reasoning.

Venous IMBUS can find deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in a leg or arm vein. If IMBUS of the right heart is normal in such a patient, a CT PE is unnecessary, and outpatient anticoagulation with an immediately acting oral anticoagulant can be started.

LEG VEIN THROMBOSIS

Most information about IMBUS for outpatient DVT comes from emergency department studies, where well-trained physicians have been equivalent to, or slightly worse, than formal leg ultrasound (US). A 2019 study (acronym HOCUS-POCUS) showed that hospitalists can also have very high sensitivity and specificity for DVT. Most series show that ≤ 20% of outpatients suspected of DVT have the disease. Expert IMBUS of the leg veins requires knowledge and experience, particularly regarding anatomy, patient positioning, and Doppler techniques. The advanced IMBUS physician recognizes a suboptimal exam and obtains formal leg US.

IMBUS of the leg veins augments the dD assay. Without IMBUS, the clinic physician’s first option is to send all patients for an immediate formal ultrasound while waiting for the dD to return later. This option is wasteful of formal US. The other option is to send all patients home while waiting for the dD result. If the dD returns positive, a formal ultrasound is performed the next day, but this strategy runs a risk that a patient with a DVT is sent home without immediate treatment. IMBUS in the clinic at least ensures that hemodynamically significant proximal leg clots won’t be missed as a patient goes home to await the dD result.

Estimate the prior probability of DVT (perhaps using the online DVT diagnostic calculator), do IMBUS, and order a dD for almost all patients. The following diagram approximates the diagnostic integration, but always consider whether over or under-diagnosis is a worse error for any patient.

A patient with a low pre-test probability of DVT (e.g., ≤10%) and a good-quality, normal IMBUS exam has a post-test probability of ≤ 2%, and a later-returning normal dD further reduces the chance to <<1%. A moderate pre-test probability patient with a normal IMBUS study needs a normal dD to get to <1% probability of DVT. If the dD is elevated instead, the patient usually requires a formal US the next day, but at least the risk of a major PE during the night is minimal. High pre-test probability patients with normal IMBUS and normal dD have post-test probabilities of DVT that may still be worrisome for some patients (2-5%), and they might need repeat IMBUS in a handful of days to be sure that visible DVT has not developed. Positive IMBUS leg vein exams should result in immediate oral outpatient anticoagulation.

Distal calf veins (veins below the second bifurcation in the popliteal region) are challenging to visualize, and there is uncertainty about treating clots in these veins. Such clots don’t cause major pulmonary emboli but can extend more proximally in a minority of patients. These patients should return immediately to the clinic if they have persisting or worsening symptoms, and some higher-risk patients should be scheduled for a repeat IMBUS exam within a week to look for an extension of the clot.

General anatomy and technique

Bilateral leg IMBUS is unnecessary when symptoms and signs are unilateral. However, if an equivocal abnormality is seen on a symptomatic side, comparison to the same area on the contralateral side is helpful. Left-leg DVT is more common than right-leg DVT because of several anatomic factors (beyond the uncommon May-Thurner syndrome), and popliteal region thrombosis is more common than the femoral region. However, the proximal leg clots are more dangerous.

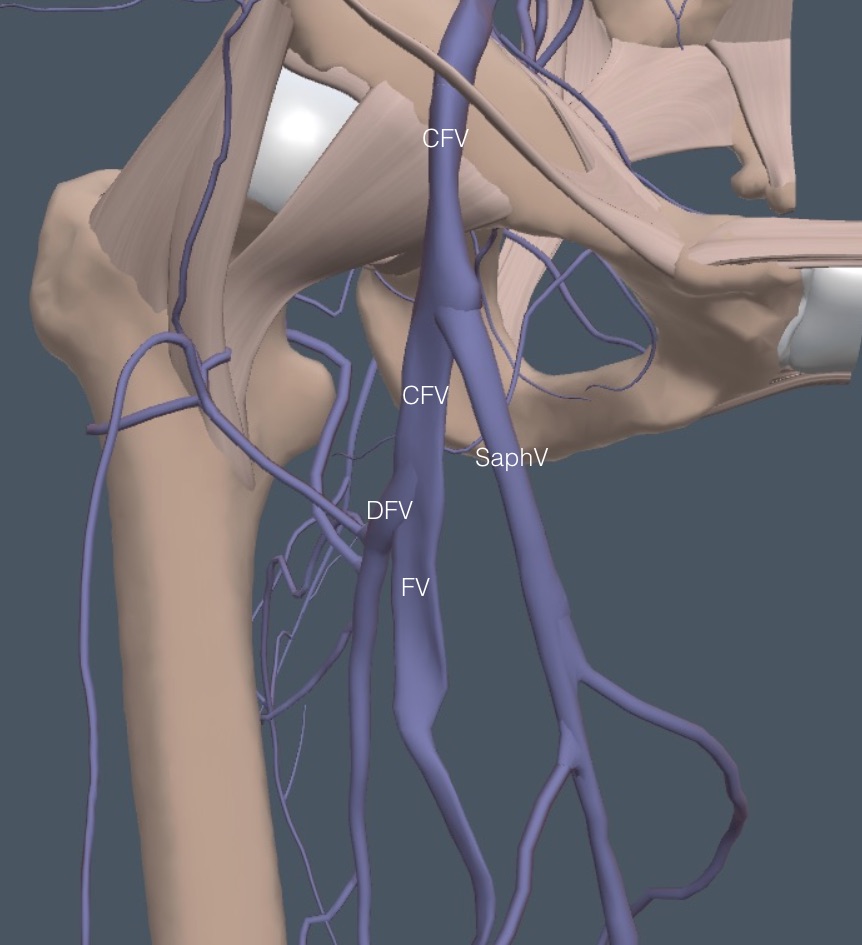

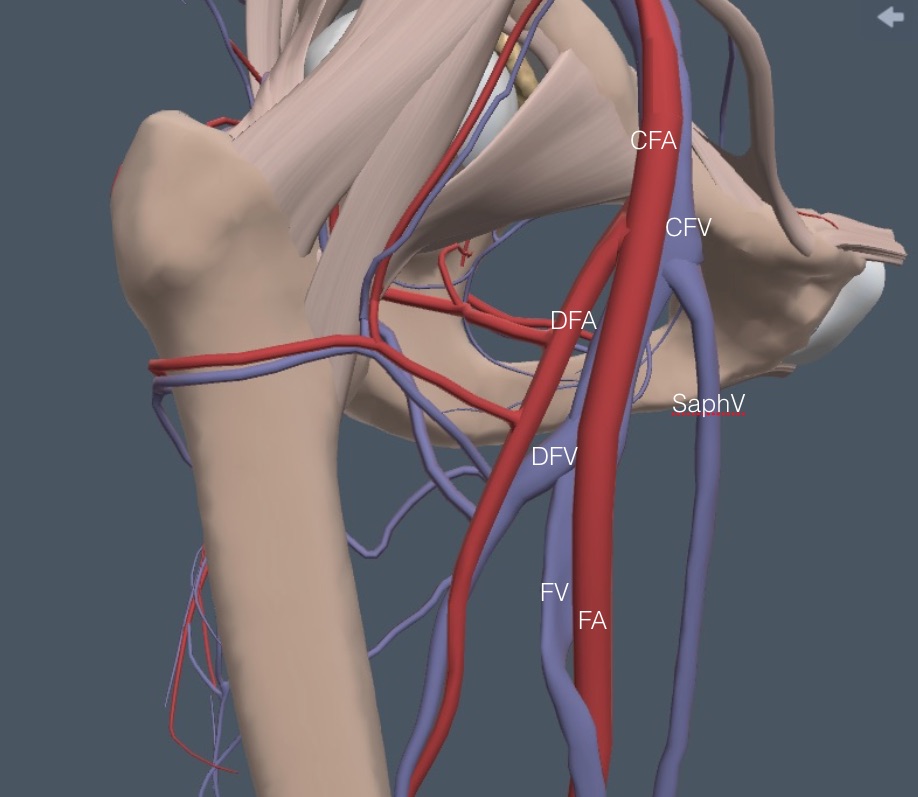

The leg anatomy diagrams in this chapter are of the right side, but the US images are from the more commonly thrombosed left leg. Although the veins flow towards the heart, the leg exam is performed from proximal to distal, so we are referring to the venous branches and bifurcations analogous to the arteries. Here is a simplified venous anatomy diagram for a brief exam overview.

The exam starts just below the inguinal ligament with the common femoral vein (CFV), proceeds through the branching of the saphenous vein (SaphV), and then the further branching of the CFV into the deep femoral vein (DFV) and the femoral vein (FV). The FV is lost about halfway down the medial thigh, running deep behind muscles. The main deep vein is seen again at the posterior knee as the FV becomes the popliteal vein (PopV), and two branchings follow this.

The blind spots are the iliac vein above the CFV and the portion of the FV between the mid-thigh and the PopV. We partly deal with these two areas with color flow Doppler (Color) and pulse wave Doppler (PW), as described later.

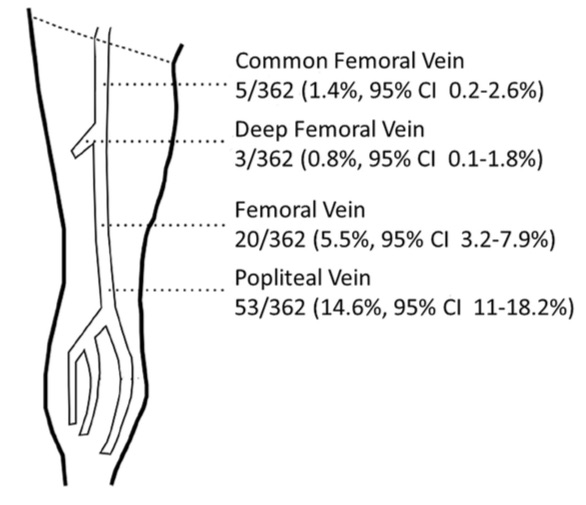

Most DVTs involve multiple sections of veins by the time the patient presents clinically. However, the following diagram shows the location of isolated DVTs in one reasonably large study. The PopV was the most common site for an isolated DVT, while the DFV was the most unusual, which is fortunate because it can be more challenging to image.

Patient positioning: Although the standard patient positioning for leg vein US has been supine, comparing the exam in the standing and supine positions convinced us that the standing position should be the default clinic approach. Here are the factors that influenced this decision and circumstances that cause reversion to a lying-down exam.

1. The veins are more distended and usually easier to see in the standing position for both the femoral and popliteal regions.

2. The linear probe is often mechanically easier to use on the popliteal area with a posterior approach in the standing position.

3. For many patients, it is easier and quicker to lower their pants to the floor and have them stand against the exam table than to remove their pants, get on the table, and get positioned. The physician sits on a rolling chair for the standing patient and lowers the ultrasound screen.

4. Although it can take more probe pressure to collapse standing veins, most patients do not find this painful. If the pressure is too uncomfortable, revert to the supine/prone exam and hope the vein visualization will remain adequate.

5. Color and PW of the CFV and PopV show respirophasic flow in the standing position, but if this is absent or equivocal in both legs in the standing position, repeat the evaluation in the supine/prone position to confirm.

6. Patients who cannot stand must be examined supine for the femoral region exam. The popliteal region is better examined in the prone position in these patients. A good solution isn’t available for wheelchair patients who can’t be moved to the exam table. Our experience suggests that the popliteal region and part of the femoral region can sometimes be seen in these patients, but the CFV view is compromised.

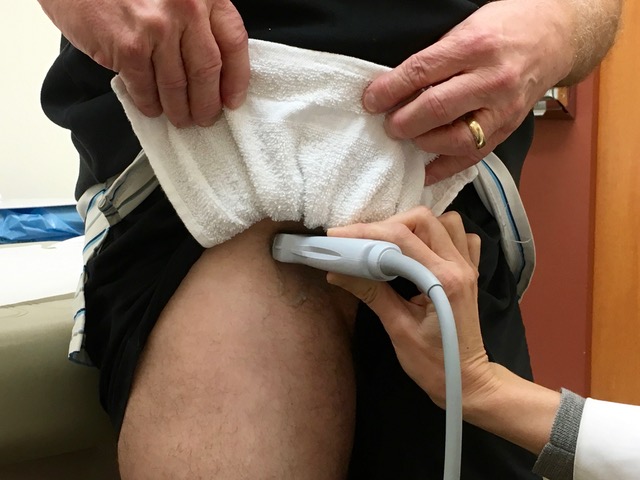

7. In the standing position, obese patients may have fat hanging down over the inguinal area. Our standard underwear draping and protection with a washcloth sling usually lifts this fatty layer. The physician creates the sling, and the patient (or helper) holds it up, as shown in the following picture.

Optimize: Optimize the depth and focus position with the linear probe and a venous exam preset. In obese, muscular, or edematous patients, decreasing the frequency may get better images. Pressure on the probe can reduce the distance to the veins, creating sharper images, but this pressure may start to collapse the veins. Optimize the gain so the vessel blood is anechoic.

Gel: The probe must infrequently be protected with a glove for the femoral region. Whether the physician wears gloves is personal taste, but it is not required in most patients. The probe will cover a large area in the femoral region, so it may make sense to pre-apply some gel to avoid leaving the leg to get more gel. However, too much gel can fall on a patient’s pants.

Compression: The primary criterion for a DVT is the “lack of complete compressibility” of a vein. The probe must be perpendicular and directly over a vein to optimize compression. The pressure needed depends on the amount and character of the overlying tissue. In general, a compression trial is not complete until there is a beginning deformation of the accompanying artery. Keep the vein centered and slowly and gradually increase pressure, often using two hands. Having patients braced against the exam table stabilizes them for this pressure. Here is an example of a left CFV that showed full compression with progressive pressure that just started to deform the common femoral artery (CFA).

Color: Color can help identify vessels, distinguish arteries from veins, separate blood vessels from other hypoechoic structures, and detect phasic flow with respiration. It can also help identify veins that are partly occluded. Here is a PopV showing a rim of Color around a mostly occluding clot. The vein was non-compressible.

Visible thrombus: With correct gain, a venous clot may show increased echogenicity with B-mode imaging. However, using the clot's appearance to differentiate between acute and chronic thrombosis is challenging. Acute thrombosis usually enlarges a vein, and recanalization seen with Color strongly favors chronic disease. The following clip shows hyperechoic material in a PopV and partial Color around it.

Stasis or slow flow in a vein can appear as spontaneous echo contrast, but if the vein fully compresses, there is no clot at that location. Here is an example of spontaneous echo contrast in a CFV that collapsed fully, but the flow progressed cephalad poorly because of a thrombus in the iliac vein above. This CFV did not have respiratory variation in Doppler flow, as discussed below.

Transverse and Longitudinal views: Most literature describes looking for DVT with a transverse view, which is better for assessing compressibility. However, a longitudinal view sometimes clarifies the anatomy or confirms an abnormality, particularly at vein-branching sites.

Sequence and Findings: Lower Extremity

START AT THE INGUINAL LIGAMENT

The patient should turn the foot outward on the leg to be examined to expose the medial thigh. Begin as cephalad as possible at the midpoint of the inguinal ligament and look for the CFV and CFA. Here is a detailed anatomy diagram of the veins in the right femoral region. Notice the two branch points. The most challenging exam area is where the DFV and FV branch.

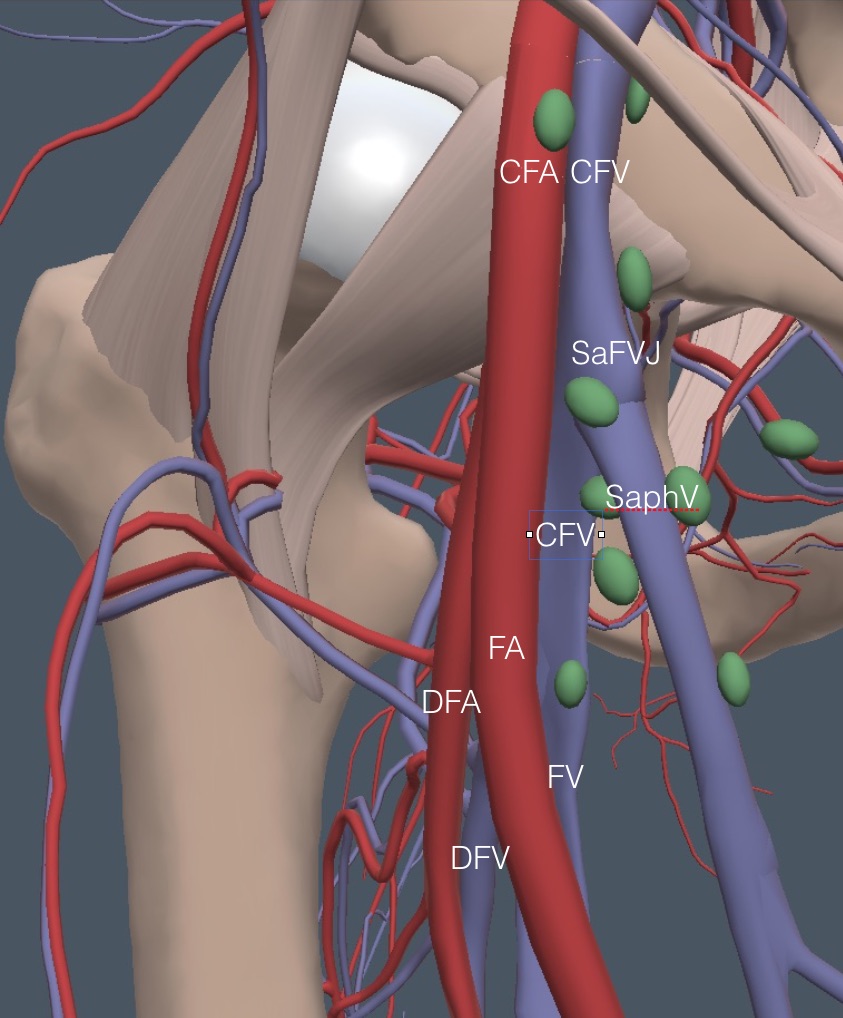

Next, for reference during the rest of this femoral region discussion, the arteries and some green ellipsoids representing lymph nodes are added. A comparably named artery accompanies each vein, except for the SaphV.

The CFV is always medial to the CFA near the inguinal ligament, as seen in the following clip from the left leg with Color applied.

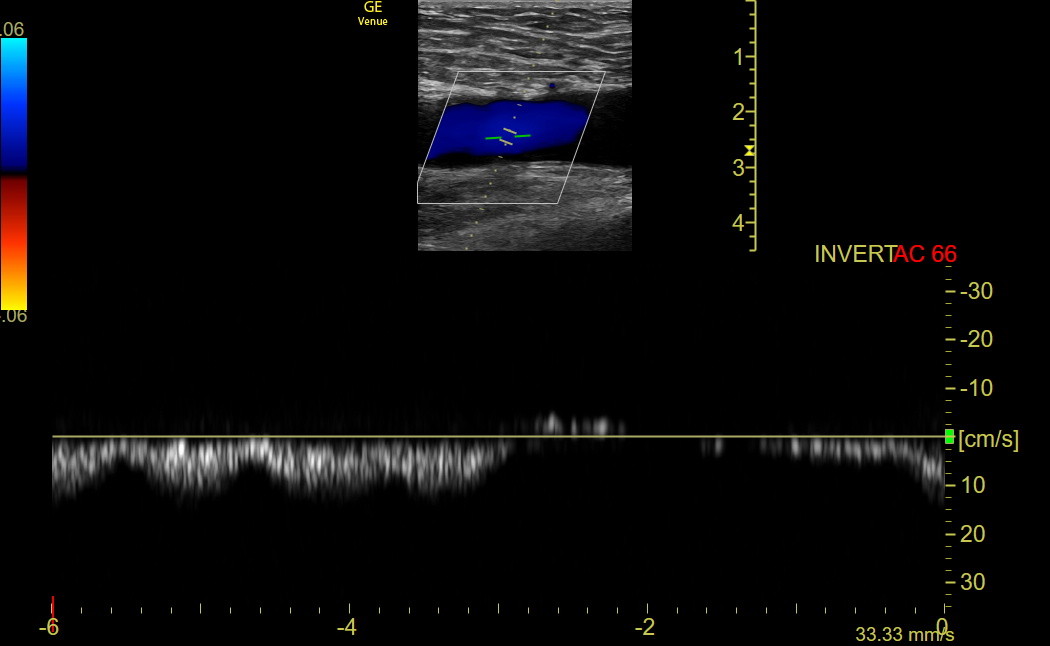

Respirophasic Flow: The longitudinal orientation in the CFV is best to assess flow velocity variation with respiration. First, use Color with the default angled sector box, showing the arterial flow from the head red and the venous flow from the lower leg blue. If the Color seems backward, change the angle with Steer or use the Invert button. If respirophasic flow is present, PW isn’t needed. Here is normal respiratory Color variation in a left CFV. As inspiration starts, the blue flow disappears for a short time.

If Color variation with respiration is uncertain, activate PW and align the cursor parallel to flow in the middle of the CFV. Once the PW tracing is activated, have the patient take a deep breath in and out. The sweep speed needs to be slow enough to encompass a respiratory cycle. Here is normal PW respiratory variation in the CFV. It doesn’t matter whether the settings show the signal above or below the line.

If the iliac vein or IVC above the CFV is blocked, PW will show a line that may move slightly with the adjacent arterial pulse, but the respiratory variation will be absent.

In some patients with a lack of CFV respirophasic variation, it is possible to visualize the distal, retroperitoneal iliac vein by moving up above the inguinal ligament. Compression isn’t possible, but Color and PW in the long axis give information.

Compression: The next step is demonstrating complete CFV compression, as shown previously.

Here is a patient with an acute thrombosis of the left CFV. The vein is larger than normal and does not compress well despite the complete collapse of the CFA. When this appearance is seen, do not compress repeatedly for fear of detaching the thrombus and causing a PE, although this is rare.

Saphenofemoral junction: Repeatedly compress the CFV every cm during a caudad slide with the probe until the saphenofemoral junction is seen on the medial side. Compress the CFV and the (great) SaphV completely, as in the following clip from a left leg. Apply Color if something looks unusual.

Here is an enlarged, thrombosed left saphenofemoral junction with echogenic material in the lumen, no Color signal, and no compressibility.

While the SaphV is a superficial vein, it is large, and thrombosis can extend into the CFV. Thus, proximal SaphV thrombosis is usually treated like a DVT. If a patient has superficial symptoms in that location, the SaphV can be followed down the medial thigh.

THE VESSELS BIFURCATE:

In most patients, a little caudad from the saphenofemoral junction, the CFA bifurcates into a more anterior femoral artery (FA) and a more posterior and lateral deep femoral artery (DFA). Shortly caudad of this arterial bifurcation the CFV bifurcates into a larger and more anteromedial FV and a smaller posterior and lateral DFV. Here is a lateral view of the anatomy that shows the DFV and DFA running posteriorly from the FV and FA, which is out of view with the linear probe.

The following clip shows a typical appearance in the left leg after the arterial bifurcation but before the venous bifurcation. The FA is anterior to the DFA, and the CFV should be compressed in this location.

The following clip shows the DFV branching and running laterally before it runs posteriorly. The venous compression leaves only the FA and DFA visible.

Here is another patient showing the DFV/FV branching and its normal compression.

If the DFV is indistinct in the transverse view, switch to long-axis to find the branch location. The DFV branches posterior to the FV. Compression can be used, but care is needed to ensure the probe is not just sliding off the vein. Here is the long-axis view of a DFV branching.

The DFV disappears posteriorly from view as the probe slides caudad, and the remaining FV is followed and compressed into the adductor canal until it disappears or can’t be compressed because of muscle tissue. Here is a clip showing the full compression of the FV as caudad as possible. It may take a lot of pressure to compress the vein in this location, and a firm two-handed grip may be needed to prevent sliding out of position.

Note: some descriptions of this exam mention lateral perforating veins appearing about where the DFV is seen. These veins exist but are not visible unless a patient has substantial venous insufficiency.

THE BACK OF THE KNEE:

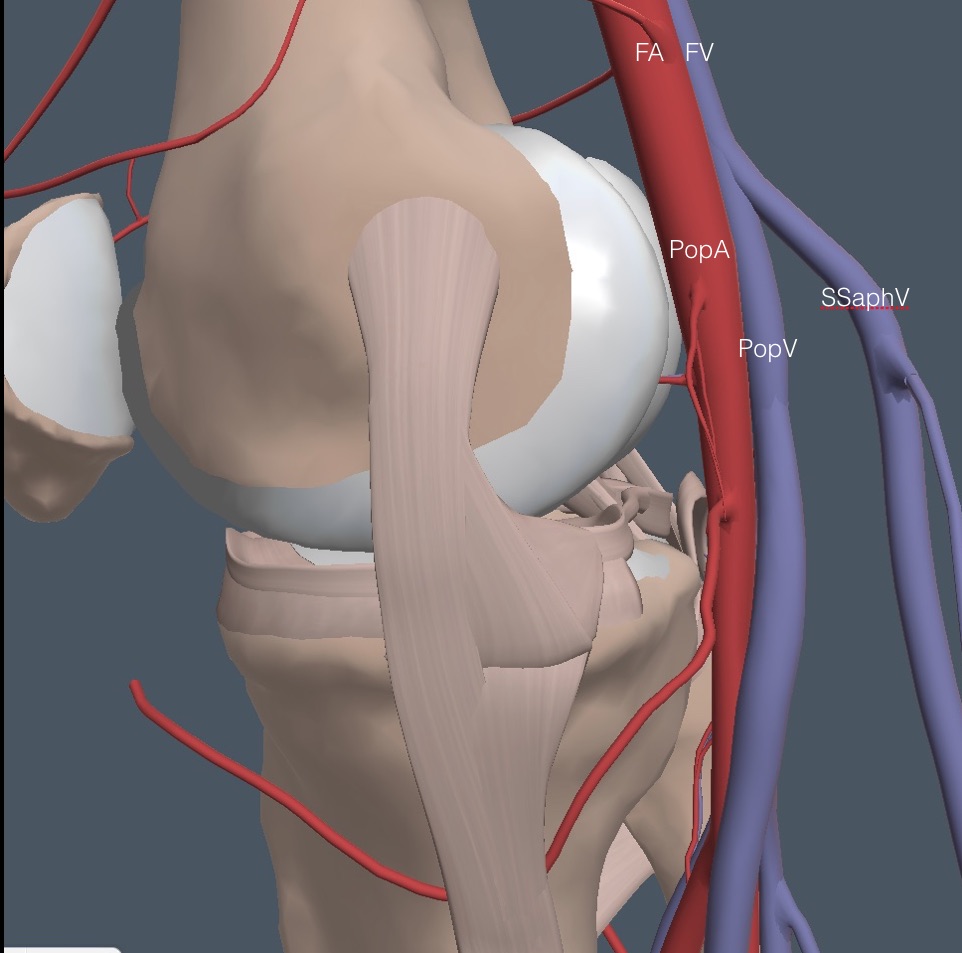

The patient turns around and stands with his back to the physician, bracing against the exam table. Apply gel to the popliteal area, and place the probe at the top of the popliteal fossa in the midline, with the indicator physician left for both legs. Sometimes, the physician’s left hand must be on the front of the knee to brace it against the probe pressure. Below is the anatomy of the region for the right leg.

The vein closest to the probe is the superficial short saphenous vein (SSaphV), which partly obscures the PopV in the diagram. Thrombosis can occur in this vein and be examined if a patient has superficial symptoms. Here is the anatomy from a lateral view showing the superficial location of the SSaphV. This vein collapses easily with light probe pressure, so it is often not seen, which doesn’t matter unless symptoms suggest superficial phlebitis.

Here is a clip showing a small, short saphenous vein at the top of the screen with the much larger popliteal vein below.

Smaller veins may be anterior to the larger PopV. These deep, muscular veins come off the PopV in this high location, and when we see them, we want to see them collapse, even if we don’t name them. However, thrombosis isolated to these smaller veins does not usually warrant anticoagulation, but a repeat study for progression might be needed. Here is a patient displaying full compression of a PopV.

Color/PW is applied to the long-axis PopV to show intact respirophasic flow, inferring that the FV in the adductor canal is at least partly patent. Here is normal Color respiratory variation in a popliteal vein.

The following clip shows an acute thrombus in a popliteal vein. The PopV is large; the superficial and small muscular veins compress, but the PopV never collapses completely.

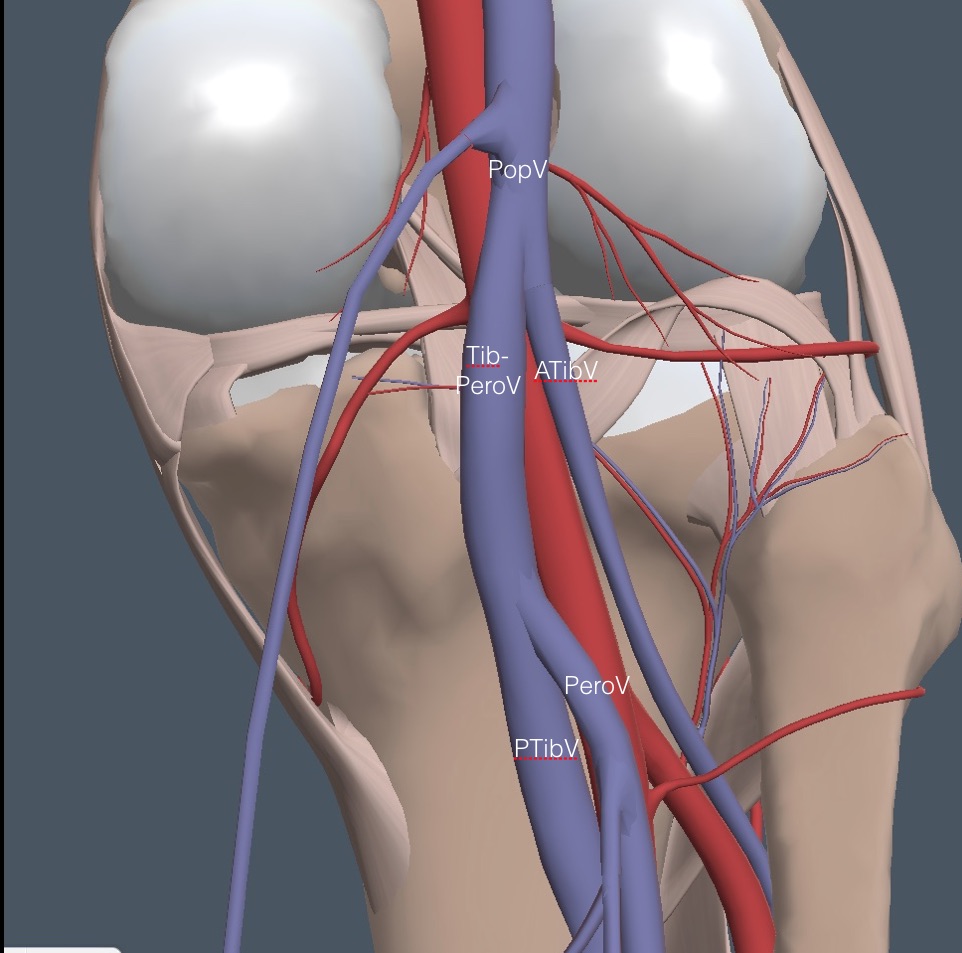

Slide the probe slowly caudad on the PopV, repeatedly compressing it until it reaches a first bifurcation. Here is a view of the anatomy with the SSaphV removed.

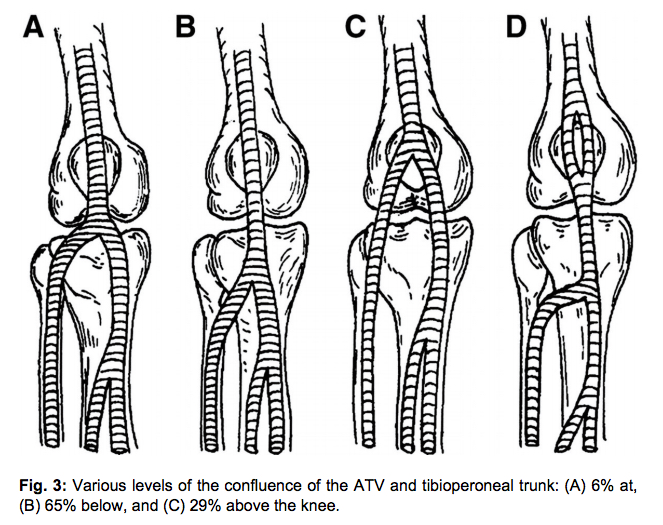

The smaller anterior tibial vein (ATibV) moves off lateral, leaving the larger tibioperoneal vein (TibPeroV) to continue into the calf. Here is a clip of a normal first branching of the PopV in the left leg, showing complete collapse of all veins with compression. The indicator on the screen represents the lateral side of the left leg.

There is some variation in where the ATibV branches, as in the following diagram drawn from the front of the right knee.

Wherever it branches, the ATibV always goes off lateral and disappears. Fortunately, isolated thrombosis of the ATibV is rare, so missing this vein is acceptable.

Slide the probe further caudad, compressing the TibPeroV until a second branch point where the larger posterior tibial (PTibV) stays medial, and the smaller peroneal vein (PeroV) runs off lateral. The following clip shows the PeroV and the accompanying peroneal artery branching off from their respective trunks. Compression shows the veins collapse.

The PeroV usually disappears quickly, and only the larger PTibV is followed and compressed as far caudad as possible. Anticoagulating clots further caudad than the origin of the PeroV is controversial. Many formal ultrasound labs don’t try to pursue the distal PTibV or PeroV, even though they are still considered deep veins, but the IMBUS exam should compress the PTibV as far distal as possible.

MIMICS AND TRAPS:

Lymph nodes: Enlarged nodes are an issue for the femoral region. Nodes are superficial to the vessels but can look like a thrombosed vein in transverse view. Even with Color, an enlarged, distorted node may be challenging to differentiate from a thrombosed vein. A longitudinal view should easily show that a node is not a vessel. In addition, with appropriate depth, the CFV and CFA should always be seen as separate and deeper than lymph nodes. Here is an enlarged and abnormal lymph node in the region of the CFV and CFA that was seen with the first probe placement for a DVT exam. The physician was initially concerned with occluding clots that might be dislodged with compression. However, the absence of a femoral artery caused the physician to increase the depth, and then a normal CFV and CFA were seen with the abnormal node anterior to the CFV.

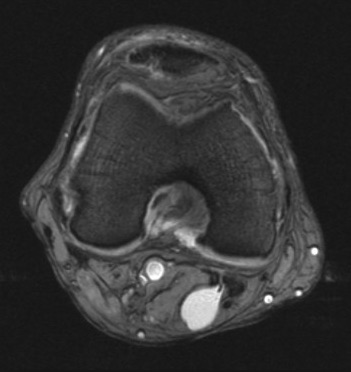

Baker/popliteal cyst: Baker cysts are fluid-filled synovial-lined sacs between the medial head of the gastrocnemius and the semimembranosus tendon about at the joint line. They communicate with the knee joint, but this communication is often difficult to see. Here is a contrast MR arthrogram of a left leg showing a Baker cyst from the medial side and spreading to the middle of the leg.

These cysts create an apostrophe or comma-shaped structure with clear borders, anechoic fluid, and internal hyperechoic signals. Here is a transverse view of a moderately large Baker cyst in the left leg.

Baker cysts start small but can become large and rupture. These synovial cysts can cause symptoms that mimic a DVT, and they can compress the PopV, resulting in a DVT. There is no Color signal in a Baker cyst, but the cyst will often compress to some extent. A longitudinal view of a Baker cyst will make clear that it is not a vessel.

ARM VEIN THROMBOSIS

DVT in the upper arm can embolize to the lung, but these clots are rarely large enough to cause hemodynamic decompensation. Repetitive embolization can infrequently lead to chronic pulmonary hypertension. Spontaneous DVT in the arm is rare and requires some narrowing of the subclavian vein because of thoracic outlet syndrome or a condition known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome in which soft tissue between the clavicle and the first rib creates stasis, particularly in patients who repetitively use their arms over their head (e.g., athletes). Here is a diagram of Paget Schroetter syndrome.

Most DVTs of the arm are postoperative after arm/shoulder surgery or the consequence of indwelling venous catheters in patients who are hyper-coagulable. Most proximal arm clots will be anticoagulated, while more distal arm clots require careful balancing of the risk of extension versus the risk of anticoagulant-related bleeding. Patients can be followed in the clinic for an extension.

Anatomy and Technique

Unless a patient has specific complaints in the lower arm, patients with arm swelling or discomfort usually receive an IMBUS exam above the elbow. Because a thrombosed arm vein looks the same on ultrasound as a clotted leg vein, only the sequence, technique, and normal images will be shown.

The first consideration is patient and physician positioning. The arm veins are better distended when the arm is slightly below heart level, which means the patient should usually be sitting. The veins should also be in a free-flowing position, which means the arm needs to be abducted. These conditions are met in the clinic exam room with the patient sitting on a chair against the exam table with the arm abducted and resting on the table, usually with the thumb up.

NOTE: The standard arm vein exam is described and performed from proximal to distal. However, a good case can be made that a distal to proximal sequence may be more efficient in some patients, particularly those with large arms. Additionally, the Venue preset for upper extremity DVT has the Color box angled +20 degrees, which displays arterial flow in red from the heart to a patient’s right arm. However, to keep the color scheme the same for a left arm, the Color box must be Steered to -20 degrees, or the Invert button should be tapped.

The traditional arm vein exam begins with the internal jugular vein (IJV), which was covered in an earlier chapter. The IJV's lack of compression is easy to see, and Color in the longitudinal view may further define the clot. Note the particular need to examine the IJV in febrile patients with severe sore throat to identify septic phlebitis of the IJ, which is Lemierre syndrome.

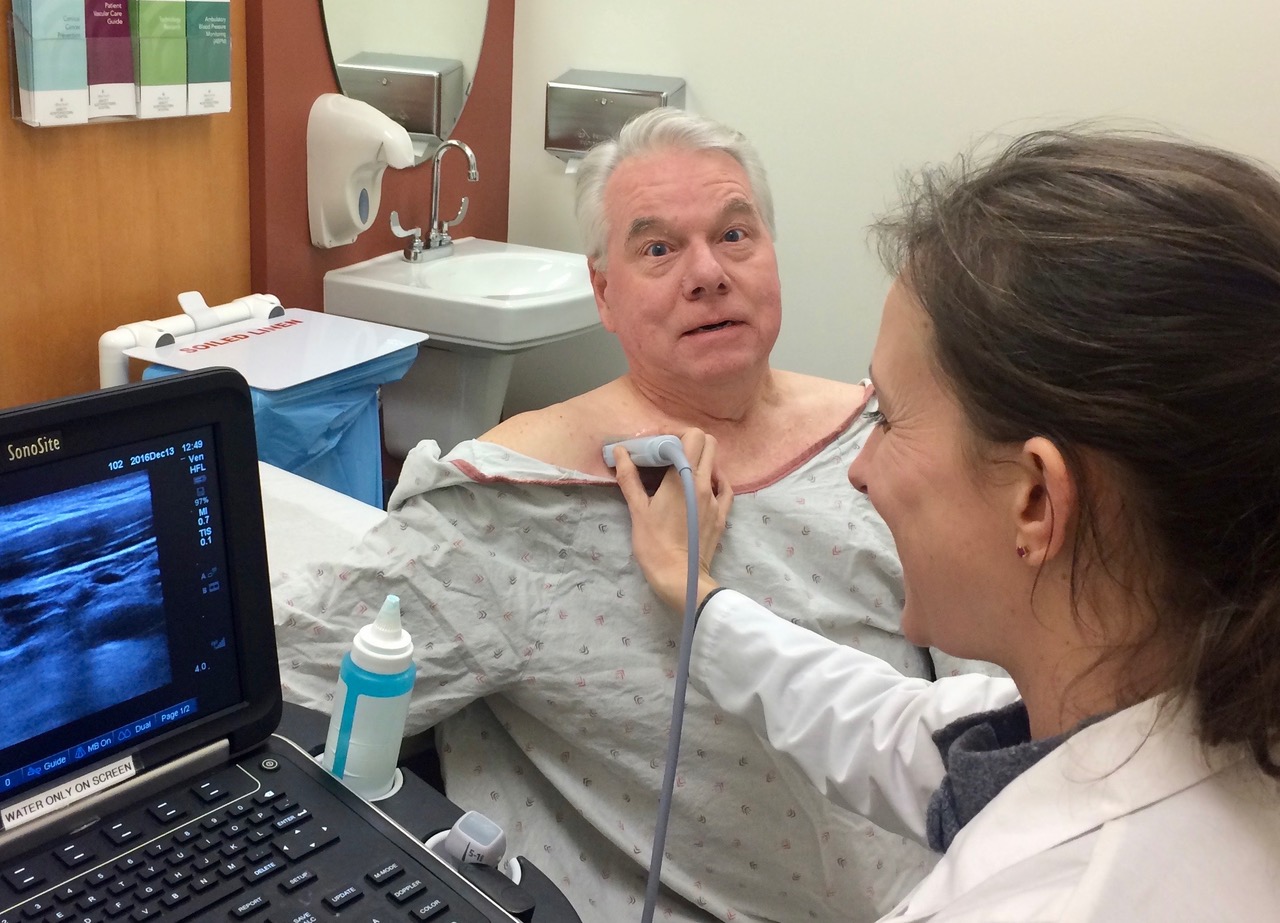

After the IJV exam, move to the proximal subclavian vein (ScV), imaging from above the clavicle. Sometimes, the ScV is easier to see from below the clavicle, as shown in the patient above. The ScV can’t be compressed in this position, but Color can show vessel flow and respirophasic variation. Here is normal Color showing inspiratory collapse in a proximal ScV.

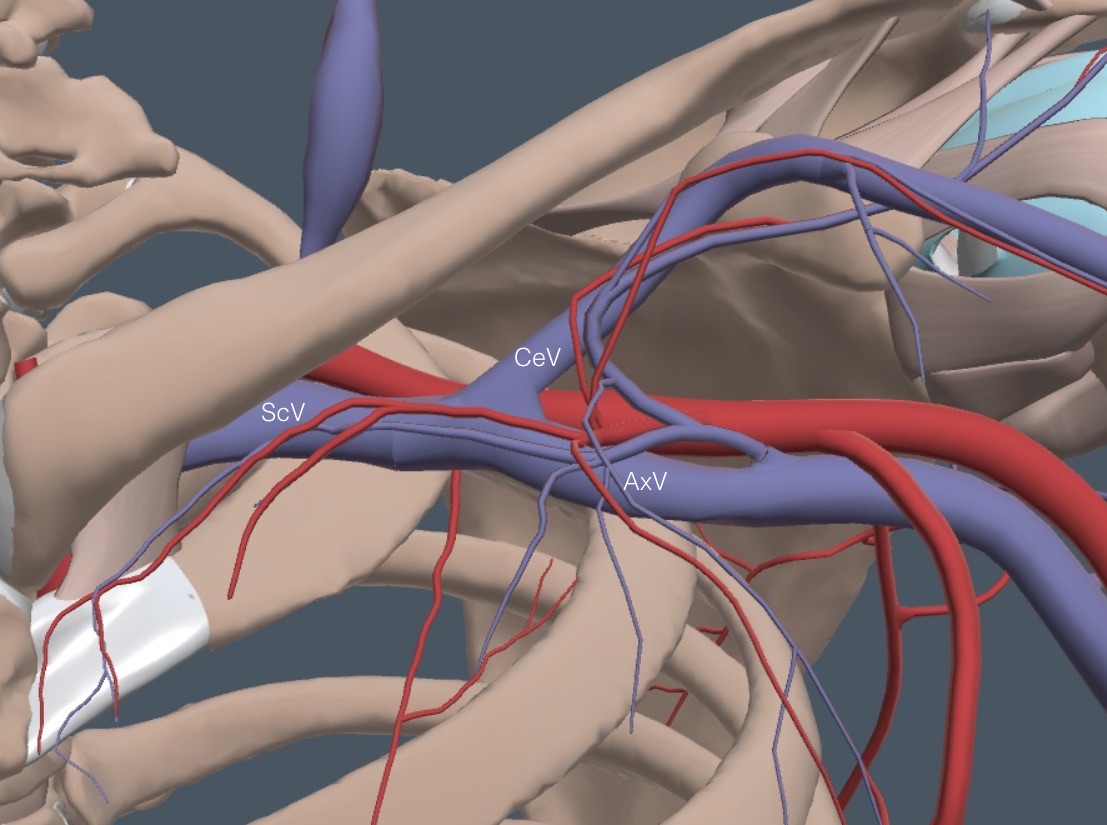

Slide above or below the clavicle toward the axilla, keeping the ScV in view using Color and watching respiratory variation. The ScV disappears as it goes between the clavicle and the first rib, but it appears again as it runs obliquely from the clavicle toward the axilla. Here is the anatomy of this area with all of the overlying muscles removed.

The ScV and the axillary artery can be seen in transverse view as they cross to the axilla. The ScV may compress, but if the overlying muscle prevents compression, apply Color in the longitudinal view to evaluate. Here is the normal compression of a ScV after the exit below the clavicle but before the axilla.

The ScV branches right before the axilla into the cephalic vein (CeV) and the axillary vein (AxV). The CeV climbs through the muscles to a superficial location and runs down the lateral surface of the arm. The CeV can develop a clot that can extend into the ScV, so it is good to see compression of the proximal CeV. Here is a clip showing the CeV branching from the ScV, both compressing normally.

After the CeV takeoff, the remaining AxV enters the axilla, and the probe position in the following picture gave a good transverse view of the vein.

Here is a clip showing the complete collapse of the early portion of an axillary vein at the bottom of the field. This is the most challenging part of the exam because of the angle the vein takes into the arm. This may be the time to move just above the elbow and follow the veins up to the axilla rather than the proximal-to-distal sequence described next.

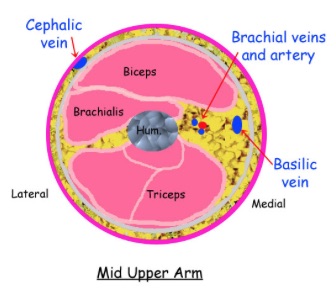

Follow and compress the AxV down the medial arm. Soon, another branch point will appear where the AxV becomes the larger and more superficial basilic vein (BaV) and the smaller, deeper brachial vein (BrV). The BrV is sometimes duplicated. The following diagram depicts this branching and emphasizes that the most prominent veins below the AxV are the superficially located CeV and BaV, which continue into the lower arm. The smaller BrV runs deeper and closer to the brachial artery and becomes the radial and ulnar veins at the elbow. All of these veins can thrombose.

The following cross-sectional drawing of the mid-upper right arm demonstrates the superficial location of the CeV on the lateral arm, the intermediate depth of the BaV on the medial arm, and the deeper location of the BrV (duplicated in this image).

Here is the probe position where the AxV branched into the BaV and BrV in a patient.

The following clip was taken just after the BaV and BrV separated. The BaV is more anterior, and the BrV is posterior and to the left of the brachial artery. Only the veins collapse.

The BaV remains larger and more superficial down to the elbow. In the following clip obtained just above the medial epicondyle, the more anterior BaV and the deeper BrV to the left of the brachial artery both compress fully.

SUPERFICIAL THROMBOPHLEBITIS (STP)

STP occurs on the extremities and trunk (e.g., Mondor disease on the upper anterior chest). STP in several locations or recurrent suggests classic Trousseau syndrome of advanced cancer. However, most cases of STP are related to minor trauma or a complication in a varicose vein. STP involving varicosities appears to have less of a tendency to extend into the deep venous system. Leg STP is almost always in the distribution of the SaphV or the SSaphV, which are superficial veins.

Treatment of isolated STP without accompanying DVT is usually symptomatic with an anti-inflammatory medication, although short-term anticoagulation for particularly prominent and symptomatic disease is understandable. One published opinion is to anticoagulate STP that involves 5 cm or more of a vessel.

STP is associated with DVT in a surprisingly high percentage of patients. While the deep veins in the region of the STP are logical sites for DVT, clots are sometimes found in the more proximal limb, so looking at the whole limb is appropriate.

We need to confirm the presence of a non-collapsible superficial vein in the symptomatic site, define the length of the STP, and confirm the patency of the deep venous system in the involved limb. If DVT is present, most patients would be anticoagulated. If the DVT is distal and a patient is at higher risk for bleeding, follow-up IMBUS looking for DVT progression is reasonable.

The following patient had local symptoms, and three superficial veins were imaged, but the middle vein did not compress. This patient would not receive anticoagulation.

In contrast, this clinic patient had prominent symptoms on the side of the knee. Thrombosed varicose veins more than 5 cm in length were seen. This patient would receive anticoagulation unless there were a high risk of bleeding.