Thyroid & Submandibular Glands

IMBUS examination of the thyroid an submandibular glands is essential for patients with lumps in the anterior neck. It is important to understand the cautions and benefits of these examinations.

THYROID

Thyroid US raises some issues for primary care. It is relatively easy to perform but requires experience to interpret and integrate the findings into clinical decision-making.

Fatal thyroid cancer is rare, but thyroid nodules are common and often found incidentally when CT, MR, and carotid US exams include the thyroid in the field. Of these accidentally discovered nodules, only about 10% are malignant. The great majority of the malignancies are small, low-grade papillary cancers that probably don’t need resection because there has been no detectable change in thyroid cancer death rate despite a significant increase in thyroid cancer resections. All of this information indicates that routine screening of all patients for thyroid cancer is hard to support.

Yet, some patients come to clinic thinking that they have seen or felt something in their lower neck. Others come because their unrelated imaging study has shown something in the thyroid. Some clinic physicians examine the neck routinely as part of an annual physical, and something may be detected. Competence at thyroid IMBUS may avoid sending some patients for formal ultrasound studies or biopsies. Recommendations from several national groups support the following approach.

Patients at increased risk: family history, radiation as a child, genetic disease with an increased risk of medullary carcinoma.

Worrisome Features of a Thyroid Nodule:

Hypoechoic

Microcalcifications

Disrupted rim calcification

Irregular margin

Taller than Wide

Extra-thyroidal spread

Purely Simple Cysts are unusual, but regardless of size, they are benign, and no biopsy is recommended. A simple thyroid cyst meets the same criteria that simple cysts of the kidney or liver must meet. Symptomatic cysts > 4 cm may still be resected. A simple cyst found with IMBUS could be followed once in clinic in 6-12 months for reassurance but then needs no, or very infrequent, imaging.

We use the online TI-RADS Calculator from the American College of Radiology for all other thyroid nodules. This was created to categorize thyroid nodules using size, cystic features, echogenicity, and the presence of worrisome features. From the category (TR1-TR5) comes the guidelines for when an FNA is needed. Patients with nodules graded greater than TR2 should also have a survey for abnormal neck lymph nodes.

TECHNIQUE AND FINDINGS

Use the linear probe with a Thyroid preset. Most patients can keep their clothes on and be draped with washcloths for the exam. The patient should lie supine and attempt to extend the neck without discomfort. The head can be slightly rotated away from the side being examined.

It makes sense to cover the area with gel before the exam. Some experts recommend starting cephalad at the laryngeal prominence and scanning transverse down the midline. This ensures you do not miss pyramidal lobes, which can contain neoplasia. Then, move to the right side and place the probe transverse, indicator physician left, above the clavicle. If the thyroid lobe is visible at the clavicle, fan down and look for a retrosternal thyroid. If no thyroid is visible at the clavicle, slide cephalad until the thyroid is seen lateral to the trachea and medial to the carotid. The probe should be angled slightly medially to get a good image. Optimize the depth, focus position, and gain. Use more gel and less pressure to avoid changing the size of some nodules.

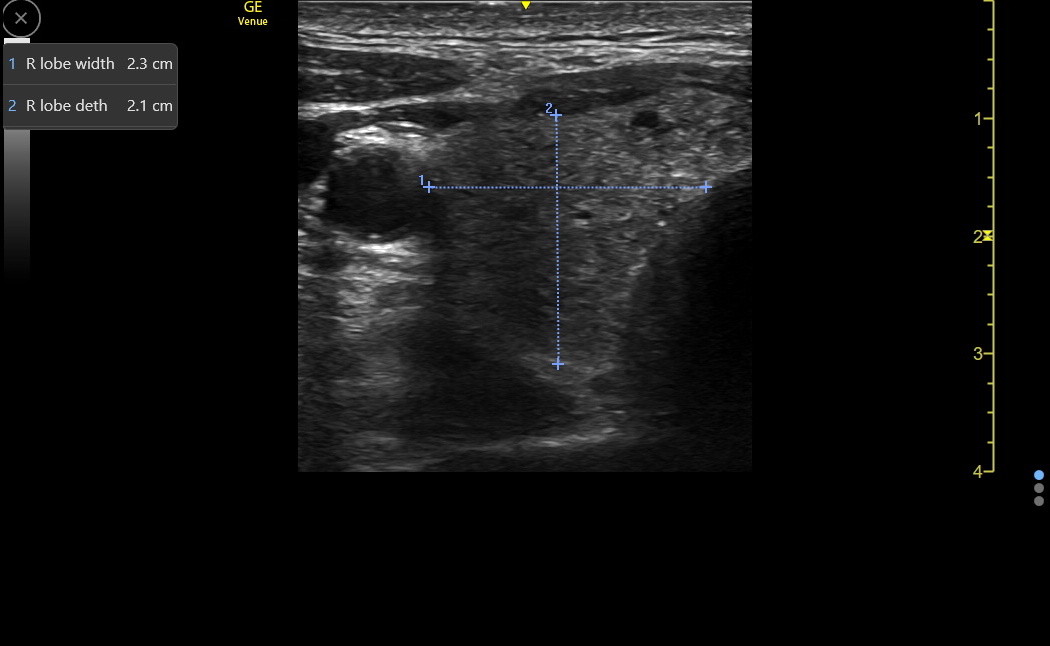

Size the right thyroid lobe before evaluating its composition. Quickly slide up and down in the transverse plane to identify where the thyroid appears the largest and FREEZE. It is usually enough for IMBUS to measure only the anterior-posterior depth of the lobe, and about 2 cm is a rough cutoff. Here is a right lobe of the thyroid with a width and depth at the upper limits of normal.

After transverse sizing of the right lobe, slowly move up and down the lobe in the transverse plane again, looking at the parenchyma. It makes sense to briefly apply Color or power Doppler to the lobe, at least to learn what normal looks like. Here is a clip from a patient with a very abnormal right thyroid.

This approximately 4 cm wide nodule in a young woman was TR3 level, considered mildly suspicious. FNA is indicated if > 2.5 cm, so this was done, and the patient had a Huerthle cell neoplasm. Given the propensity for Huerthle cell to spread, the right lobe was resected, and the final pathology was a Huerthle cell adenoma rather than carcinoma.

After the transverse evaluation of the right lobe, rotate the probe to the parasagittal plane, indicator cephalad. Normal cephalad/caudad length is greater than the aperture of our linear probe, so it is impossible to measure the length of the lobe accurately. Fortunately, it is rare for a thyroid to be enlarged only because of its length. Here is a long axis of a normal right thyroid lobe. There is some remaining lobe off the screen.

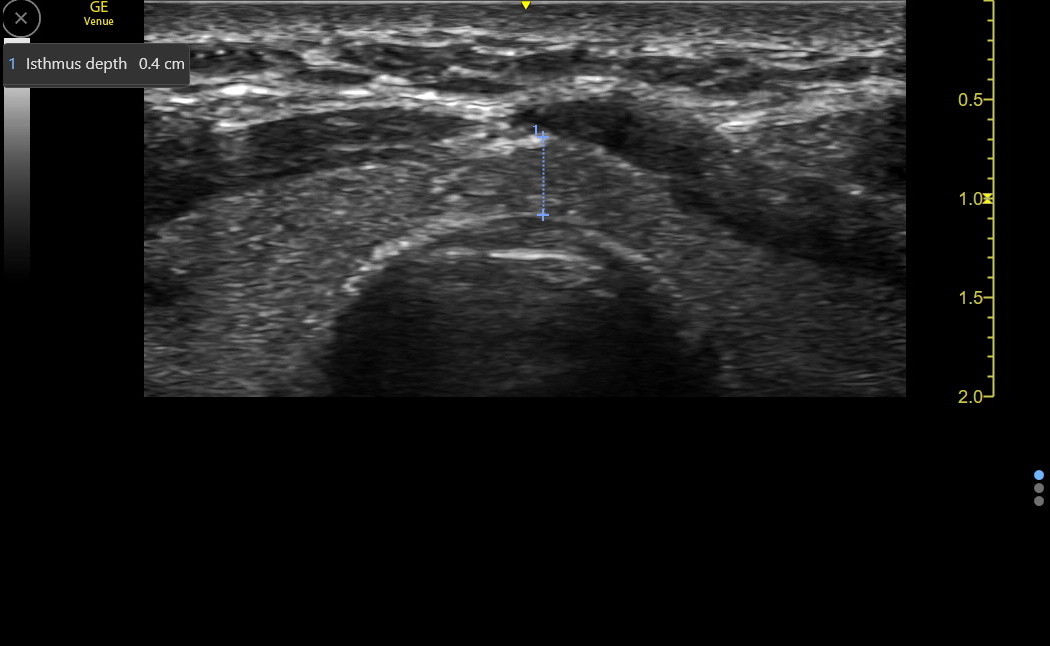

Cross over the trachea and evaluate the isthmus before switching to the left thyroid lobe. A normal isthmus should be less than 0.5 cm in depth, but this is rarely increased in isolation, so routine measurement is unnecessary if the lobes are normal. Here is a transverse isthmus in a normal adult.

The left thyroid lobe is examined in the same order as the right: transverse evaluation followed by the longitudinal. The probe indicator stays physician left, which shows the anatomy in correct position, with the carotid artery lateral to the thyroid. Here is a transverse view of a left thyroid lobe. There appears to be a cystic/solid nodule in the posterior area of the lobe, but this is part of the cervical esophagus. This will be discussed a bit more below.

The following clip is from a screening exam of an asymptomatic patient. This nodule was too anterior to be esophagus and was mixed solid and cystic. It measured 1.0 x 0.5 cm and had no worrisome features. This nodule had a low probability for malignancy and could be followed periodically, watching for a size increase over 2.0 cm before a formal ultrasound was obtained.

Here is a slightly larger left thyroid nodule that was solid and isoechoic. It was 1.25 x 1.0 cm and had a thin hypoechoic halo, which may be a good sign in the thyroid. If there were no other worrisome features, this nodule would also be low suspicion for malignancy and would be followed with IMBUS until it reached 1.5 cm. However, this nodule was modestly deeper than it was wide, so the follow-up interval was shortened to 6 months to be sure that change was detected.

Here is the longitudinal view of the left thyroid with a cystic/solid lesion in the posterior lobe, suspicious for the cervical esophagus, which became more evident in this view. During the clip, the patient gently swallowed a little saliva.

SUBMANDIBULAR GLAND

High anterior neck lumps can be in the submandibular gland (SmG) and asymptomatic or uncomfortable, depending on the cause. A competent IMBUS exam can localize a lump to the SmG, and some of the etiologies can be clear and require no further diagnostic study. The probe and the exam type are the same as for the thyroid,

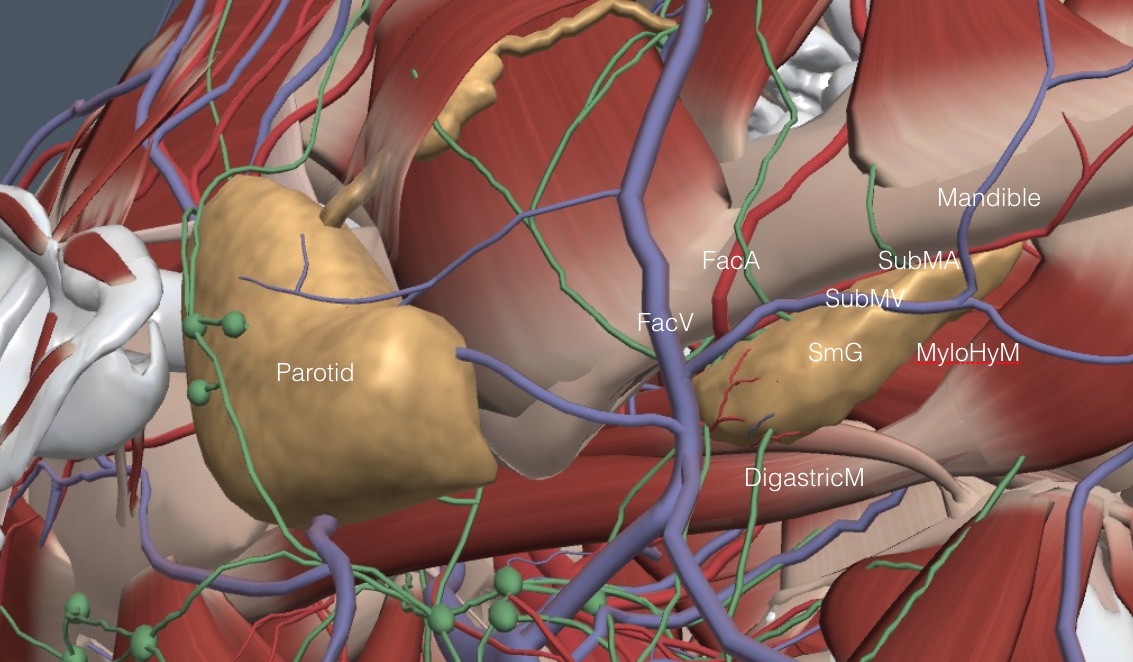

The SmGs are salivary glands smaller than the parotids but larger than the sublingual glands. The SmGs lie transversely under the midpoint of the mandible, as shown in the following image of the right upper neck.

Nodules in the submandibular gland are less common than in the parotid but more likely malignant. Pleomorphic adenoma is the most common benign lesion, sometimes still resected. Nodules > 1 cm should be pursued; smaller nodules can be followed with IMBUS for size change. The larger the nodule, the more necessary a CT or MR is to assess local invasion or dissemination before the biopsy. Ultrasound-guided FNA or core needle biopsy is needed in most situations.

The key anatomic features are the digastric muscle (DigastricM), which lies directly caudal and a bit internal to the SmG, the parasagittal oriented facial vein (FacV) and artery (FacA) at the end of the SmG closest to the ear, and the submental vein (SubMV) and artery (SubMA) that run transverse with the SmG under the mandible. The peculiar mylohyoid muscle (MyloHyM) comes from above and partially splits the chin-end of the SmG, but this muscle is only sometimes seen well with IMBUS.

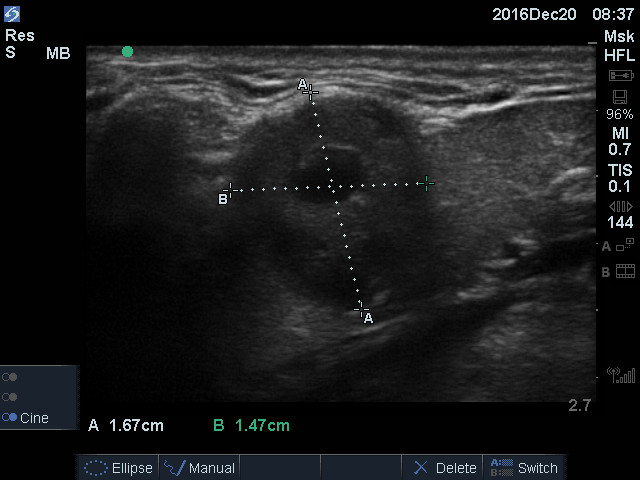

An IMBUS exam of the SmG can be kept simple. A transverse probe placement under the mandible (indicator physician left for both sides of the neck) is usually all that is needed. The gland should have a homogeneous echotexture similar to a normal thyroid gland. The hypoechoic DigastricM is posterior to the SmG and can suggest a fluid-filled structure depending on the gain setting. An adult SmG should be ≤ 3 cm in length. Here is a normal right SmG. The digastric muscle with this gain did not appear like fluid.

An infrequent abnormality in adults is a branchial cleft cyst, which can occur posterior to the SmG and push the SmG anteriorly. Don’t confuse a normal hypoechoic DigastricM with a small branchial cleft cyst. Varying the gain should help distinguish muscle from a fluid-filled structure, and the cyst should have some posterior acoustic enhancement.

Arteries and veins appear in some scan planes but are easily identified with color flow or power Doppler. The SmG duct (Wharton) runs transversely through the gland to the floor of the mouth and is not seen unless it is enlarged. It may appear as a vessel but will not have Doppler flow. The whole duct can dilate with an obstruction near the floor of the mouth, or only the distal duct will dilate if the stone is in the middle of the gland.

Here is a clip of a normal left SmG. Because the indicator remains physician left, the ear-end of the SmG is now at the right side of the screen. A few vessels are briefly seen.

The SmG can be affected by stones, cysts, infections, adenomas/ adenocarcinoma, and infiltrative diseases like Sjogren syndrome and MALT lymphomas. Simple cysts can be diagnosed with IMBUS, and reassurance can be given without additional imaging. Most solid lesions will need formal high-resolution US.

The following clip is from a clinic patient complaining of swelling under the left jaw. The SmG was enlarged, and a substantial stone with posterior shadowing was seen. The duct distal to the stone (right side of the image) was dilated.

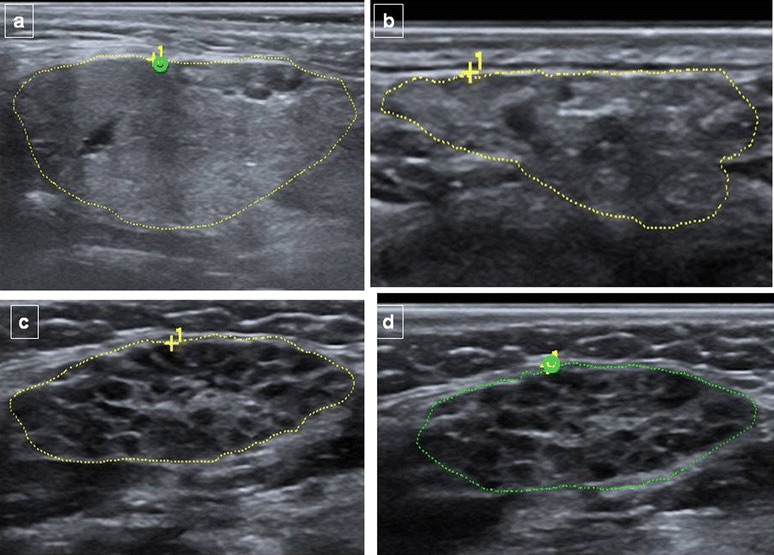

Infiltrative disease shows very heterogeneous gland tissue. The following composite image shows submandibular glands varying from normal (top left) through early and more advanced Sjogren syndrome. The heterogeneity is evident even in the early stages.

This last image is from a clinic patient who noticed a lump in the upper neck. The SmG lesion was solid with a small fluid-filled center. A biopsy diagnosed an adenocarcinoma, and the patient had a resection.