Mitral Valve

An overview of mitral valve pathology and its assessment with POCUS

MITRAL STENOSIS (MS)

MS is uncommon in the primary care clinic because rheumatic mitral disease has become rare. Mitral annular calcification (MAC) is common in elderly patients, and leaflet tips and chordae can thicken, but these infrequently cause clinically meaningful stenosis. MAC and calcific aortic stenosis are often associated, and calcification of these annuli strongly correlates with atherosclerotic vascular disease.

Here is a PLAX of a patient with reasonably extensive MAC and some restricted mitral valve (MV) movement. This patient also had calcification and restricted movement of the aortic valve, and DUST was present.

The next clinic patient had marked calcification of the MV (and the AV), and MV movement looked very restricted.

The PSAX of this patient also showed impressive calcification and restricted valve movement.

When the suspicion of MS exists, the additional IMBUS tools are only semi-quantitative. The first indicator of severity is Color in the apical views. Look for increased flow velocity into the LV that results in a “candle flame” appearance because of the narrowing and aliasing of the flow. It is appropriate to look for this in the apical4, apical2, and apical3 views because they each look at the LV inflow jet from a different angle.

Here is an apical Color clip from the prior clinic patient showing a narrowed and aliased inflow jet.

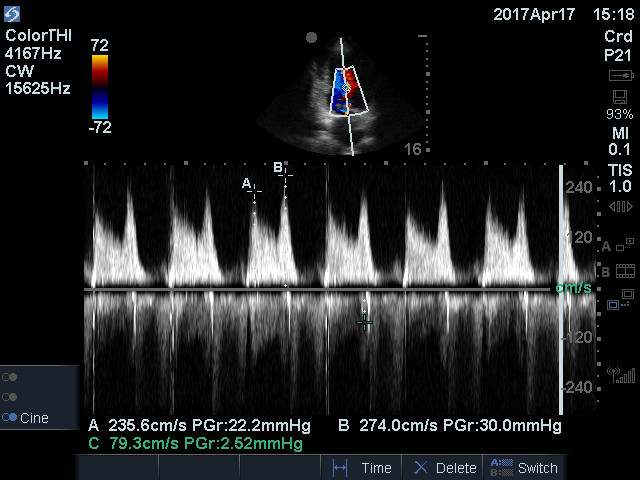

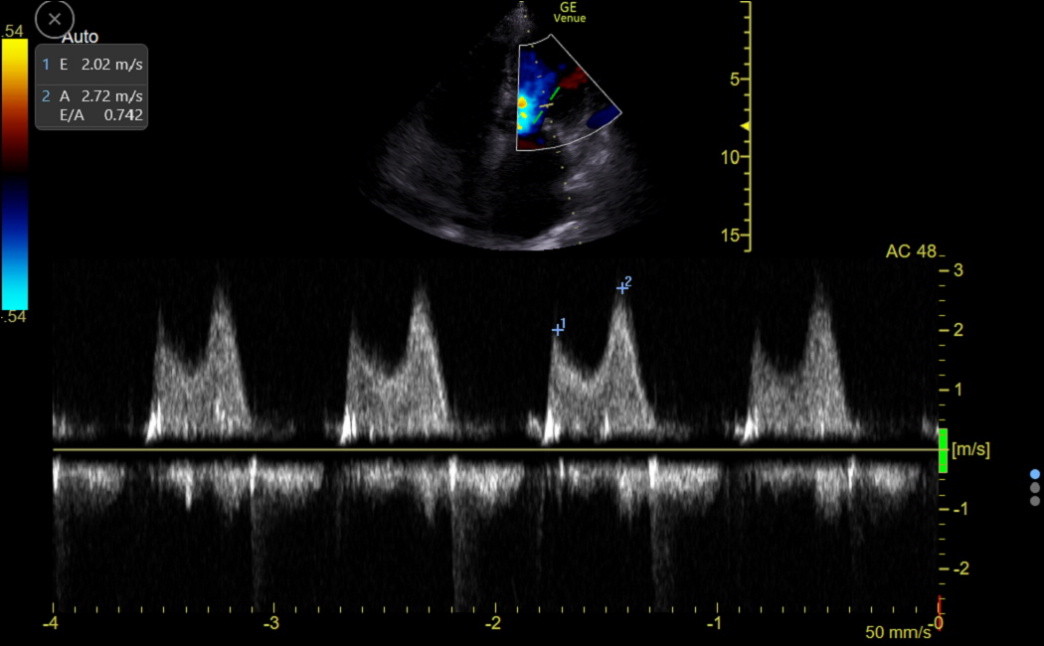

Continuous wave Doppler can also help evaluate the LV inflow. In rheumatic MS, the E velocity is high and never returns to the baseline. Here is an older tracing from a clinic patient with rheumatic MS.

Notice the high E-peak velocity of 2.4 m/sec and the elevated velocity throughout diastole. Next is the CW tracing of a clinic patient with MAC and an elevated E and A wave pattern. This patient likely needed a procedure to fix the MS.

MITRAL VALVE PROLAPSE (MVP)

This is a complicated, controversial, and sometimes over-diagnosed disease that occurs in 2-3% of the population, more often in women. But it is a cause of mitral regurgitation, heart failure, arrythmias, infective endocarditis, and stroke. Various genetic predispositions can lead to MVP. In simplest terms, mild MVP without mitral regurgitation (MR) needs infrequent follow-up. Once MR is present, follow-up needs to be more frequent because the progression of the MR cannot be predicted. Ruptured chordal structures and even flail leaflets cause a more rapid decline.

In addition, as MR becomes significant, the risk of endocarditis becomes higher in relative terms but still very low in absolute terms. The ID and Cardiology Society's recommendations against antibiotic prophylaxis for MVP are based on older population estimates considering whether an MR murmur was heard. The presence or absence of a murmur is a poor surrogate for the severity of MR. Nevertheless, since the absolute incidence of endocarditis in MVP with even severe MR is not greater than 1 in 2000, the society's recommendations against antibiotic prophylaxis make sense for most patients. Still, worrying about an MVP patient with substantial MR is justified.

MVP isn’t just a slight bowing of a leaflet back towards the LA in the apical4 view because slight bowing can be normal. The whole valve apparatus in the PLAX and apical views should be evaluated. MVP should have increased thickening of the mitral leaflets and sub-valvular apparatus without sclerosis. The chordae may also be floppy and elongated. A final characteristic feature is a rocking motion of the posterior-lateral mitral annulus. The following PLAX from a clinic patient shows a characteristic floppy MV from redundant tissue, and the annulus had an exaggerated rocking motion.

After identifying MVP, it is essential to look carefully for MR. Suppose a patient has a slight bowing but no thickness or excess tissue in the valve apparatus and no MR. In that case, we should be reluctant to label the patient with MVP or recommend formal echocardiography.

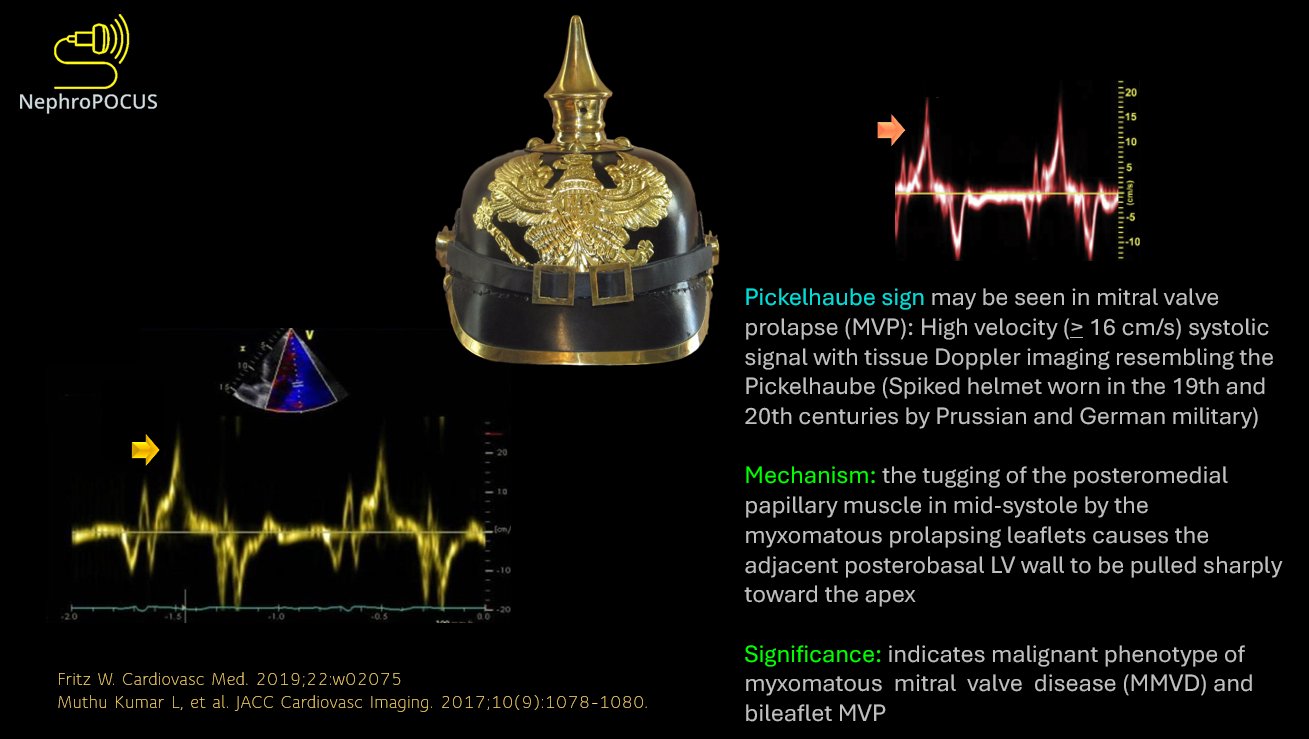

There is an uncommon but more dangerous form of myxomatous mitral valve disease with hypermobility of the MV annulus. This may be suggested visually, but an excellent sign can be identified in the TDI tracing of the lateral annulus. There is an abnormally high, spiked s’, called a Pickelhaube sign, named after the appearance of the WW1-era German army helmet. Here is a Twitter post summarizing the sign.

MITRAL REGURGITATION (MR)

Trace MR is common and by itself has no impact on patient prognosis. Acute MR would rarely be seen in the clinic because these patients quickly become acutely ill. The rest of this section focuses on chronic MR. Importantly, the severity category of an MR jet can vary substantially depending on a patient’s preload, afterload, and contractile state. The main views to evaluate MR are apical4, apical2, and apical3.

Chronic MR, as it progresses, is a volume overload on the LV, and the intermediate consequences are LA enlargement and a somewhat hyper-contractile LV that eventually begins to dilate. The mitral annulus dilation can worsen the MR in a vicious cycle. Finally, LA pressure increase is enough to cause secondary pulmonary hypertension. In the final phase, LV function decreases and cannot keep up with the excess volume.

As with AR, careful attention must be paid to the consequences of MR by carefully measuring LV and LA size, LV longitudinal systolic function, and the tricuspid gradient. We must watch for changes over time. Remember that e’ becomes unreliable when ≥ moderate MR is present, so E/e’ does not reflect LAP accurately. The valve must be corrected before LV function drops below normal. The LV EF always looks visually better than it is because of the reduced afterload created by the MR. The EF almost always deteriorates after MV repair (or replacement) because the afterload acutely increases.

Quantification of MR is otherwise done equivalently to AR, looking primarily for the presence and size of the flow convergence zone and the width of the vena contracta. Expert consensus puts less emphasis on the length and width of the jet. The MR should be assessed in every possible view because jets can be eccentric. As a simplification, functional MR from LV dilation causes central MR jets, while eccentric MR jets indicate structural disease of the MV. Eccentric jets that are wall-huggers (Coanda effect) always appear less severe than they are until the most proximal part of the jet is analyzed. Here is a table virtually identical to the AR table to help assess MR severity.

MR Classification |

Mild |

Moderate |

Severe |

Flow convergence |

Minimal to none |

Detectable but small |

Prominent |

Vena contracta |

thin |

medium |

wide |

Jet area |

Small, < 20% of LA |

In between |

Large, > 40% of LA |

Next is an example of moderate MR in an apical4 view.

Finally, here is a patient with severe MR.