Abdominal Vessels Including Aorta

The upper abdominal vessels are essential for several disease states and are landmarks for a few abdominal structures. Examining the abdominal aorta well is critical because it may become aneurysmal.

UPPER ABDOMINAL VESSELS

This exam is performed on a supine patient using the curvilinear probe in a transverse orientation. Most of the vessels are viewed short-axis.

Step 1: Transverse high epigastrium

Begin in the epigastrium and adjust the depth so only the top layer of the vertebrae is visible. The abdominal aorta (AA) should be anterior and slightly to the right of the vertebrae on the screen. The inferior vena cava (IVC) will be to the left. The following clip, obtained with halted breathing, shows the correct orientation with the expected difference in pulsation between the IVC and AA. The distal stomach partly obscures the aorta.

The normal IVC is elliptical, and color flow Doppler (Color) will show a double pulse compared with the single pulse of the AA.

Step 2: A little caudad

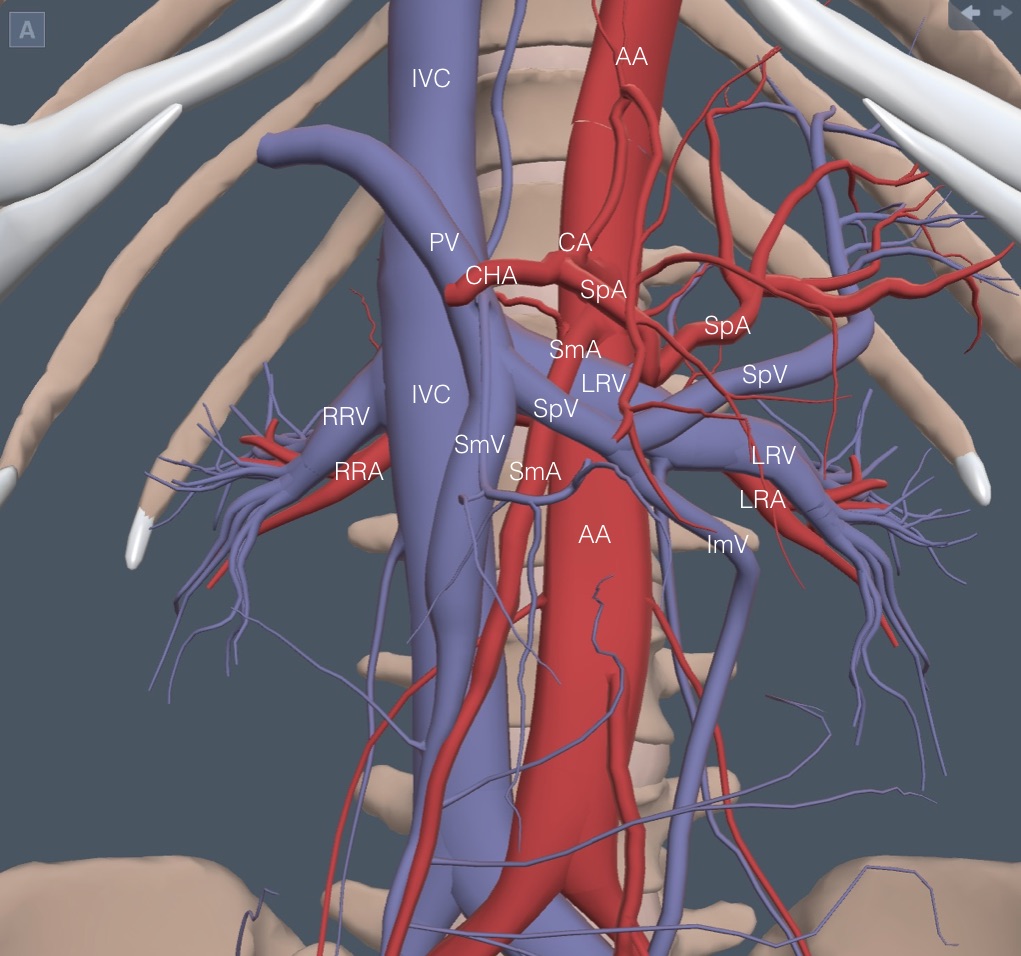

A reference anatomy picture is needed for the next group of vessels. It is less complex than a first glance may indicate because many vessels are labeled proximally and distally. It doesn’t take many repetitions of this exam to learn the relationship of the few vessels that matter.

The celiac artery (CA) is the first structure arising from the anterior wall of the aorta. The following clip shows the “seagull wings” of the CA with the splenic artery (SpA) flowing to the patient’s left and the common hepatic artery (CHA) to the right. To the left in the clip is a cross-section through the extrahepatic portal vein (PV), which is anterior to the IVC and posterior to the CHA. The PV is always anterior to the IVC.

Step 3: 1 cm caudad

About 1 cm caudad from the CA, several vessels appear close together. The superior mesenteric artery (SmA) takes off from the anterior aorta and runs obliquely caudad and medial. Because of the encasing tissue, it has a thick hyperechoic wall that can make it look like an old-fashioned “mantle clock” sitting on top of the AA. Here is a SmA on top of the AA. The IVC is lower left and pulsating. The right renal artery is posterior to the IVC.

Almost immediately caudad from the SmA takeoff, the left renal vein (LRV) comes up and over the aorta to join the IVC. It flows under the SmA, usually thin and pinched with a more dilated section right before the SmA. Here is a normal LRV. The right renal artery is still prominent posterior to the IVC.

The right renal vein enters the IVC on the right lateral side, which is not seen with epigastric views.

Immediately caudad of the LRV crossing, the splenic vein (SpV) comes over the SmA to join the superior mesenteric vein (SmV), flowing cephalad from the abdomen. This merger is the beginning of the PV. As discussed in a future chapter, the SpV is critical to identifying the pancreas. Here is a good view of the splenic vein running over the SmA.

Caudad from the SpV, any vein seen anterior to the IVC will be the SmV. The right renal artery runs posterior to the IVC, while the left renal artery runs posterior to the LRV and is usually more challenging to see. Here is a clip again showing a prominent right renal artery and a more indistinct left renal artery.

ABDOMINAL AORTA

IMBUS screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is accurate, low-cost, and justifiable once in patients over 65 in our clinic. However, due to the expense of formal radiology exams, the current national screening guidelines restrict screening to current or former smokers, particularly males. The incidence of AAA has decreased substantially over the last 30 years, decreasing the cost-effectiveness of formal screening and increasing the advantage of high-quality IMBUS screening for AAA.

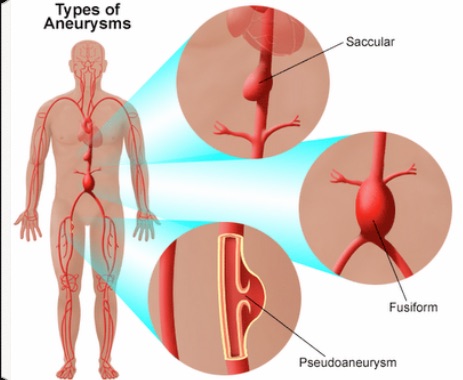

Aneurysms of the AA are rare down to the level of the renal arteries, so our search begins once we see the splenic vein, which is close to the origin of the renal arteries. The AA varies in size based on patient height, but generally, an aneurysm is defined as greater than 3 cm in greatest diameter. However, the worry point doesn’t come until an AAA is over 4 cm and intervention takes place around 5 cm.

While the longitudinal view of the AA can help find some challenging AA, the standards for measuring the AA are for transverse views. In particular, the transverse view helps avoid missing the unusual saccular aneurysm. Reduce the depth as the AA moves anteriorly in the mid-abdomen. Use as much pressure as the patient can tolerate to get close to the AA. Changing the Frequency from GEN to PEN can help with a deep abdomen.

AA measurement: Follow and periodically measure the AA from the SmA down to where it bifurcates into the iliac arteries. Isolated iliac artery aneurysms (diameter > 1.5 cm) are rare, but such aneurysms are common in association with distal AAA. The AA may be intermittently lost because of overlying bowel gas, but the gaps are acceptable if they are short and book-ended with normal aorta. The measurement of the AA that matters is the greatest diameter wherever it occurs.

There are two issues with the measurement technique. The first is that the probe needs to be perpendicular to the aorta, or falsely high values may result. It may be harder to get perpendicular as a AAA gets larger. Usually, the most perpendicular view also gives the most precise image of the AA. Repeated measurements should be performed with any large AA.

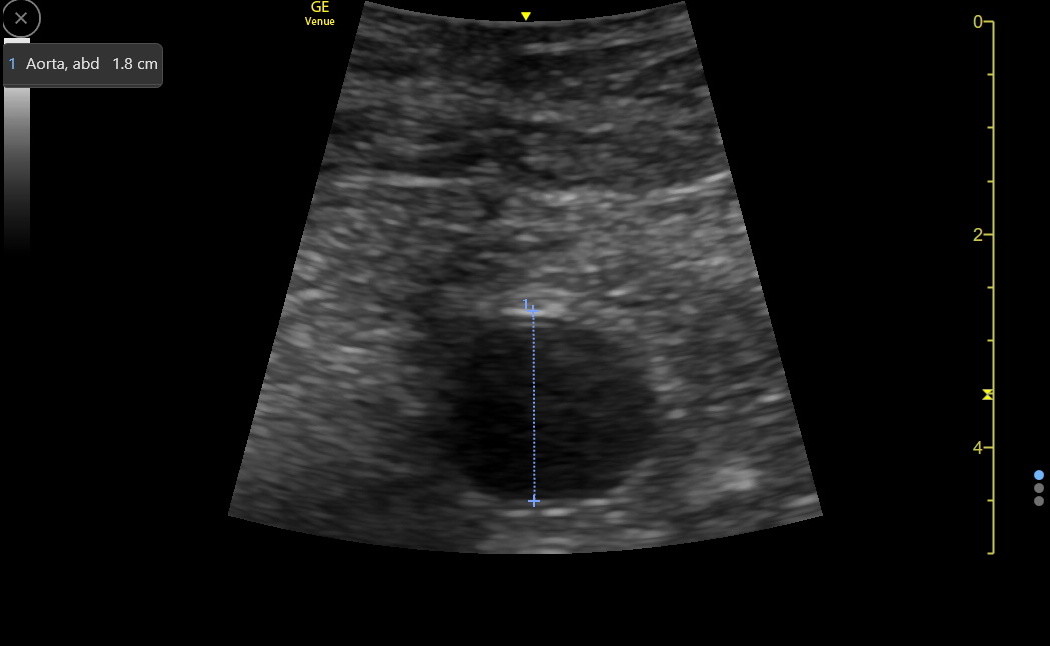

The second issue concerns the method of measuring across the AA, and there are two parts to this issue. An ultrasound physics principle called the “blooming effect” causes over-estimating vessel wall thickness in transverse view. More accurate results for the AA are thought to result from the “leading edge to leading edge” (LELE) method, in which the first cursor placement is at the beginning of the hyperechoic anterior wall of the AA, and the second cursor is placed at the start of the hyperechoic posterior wall. Here is a normal AA measured with LELE.

This differs from a commonly taught “outer to outer” measurement method. Many labs don’t specify their technique. A related issue concerns the presence of thrombus in the lumen as a AAA gets larger. The diameter of the aorta can be underestimated if we put the posterior cursor at the beginning of the thrombus rather than at the start of the posterior wall. Here is a clip of a moderate-sized AAA that had a thrombus visible posteriorly.

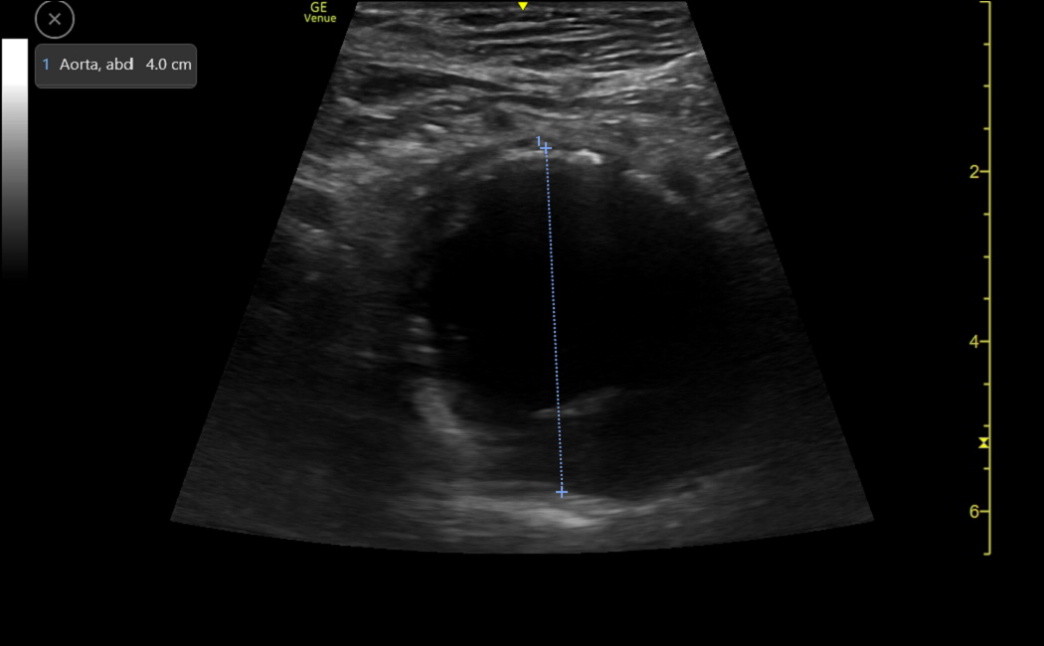

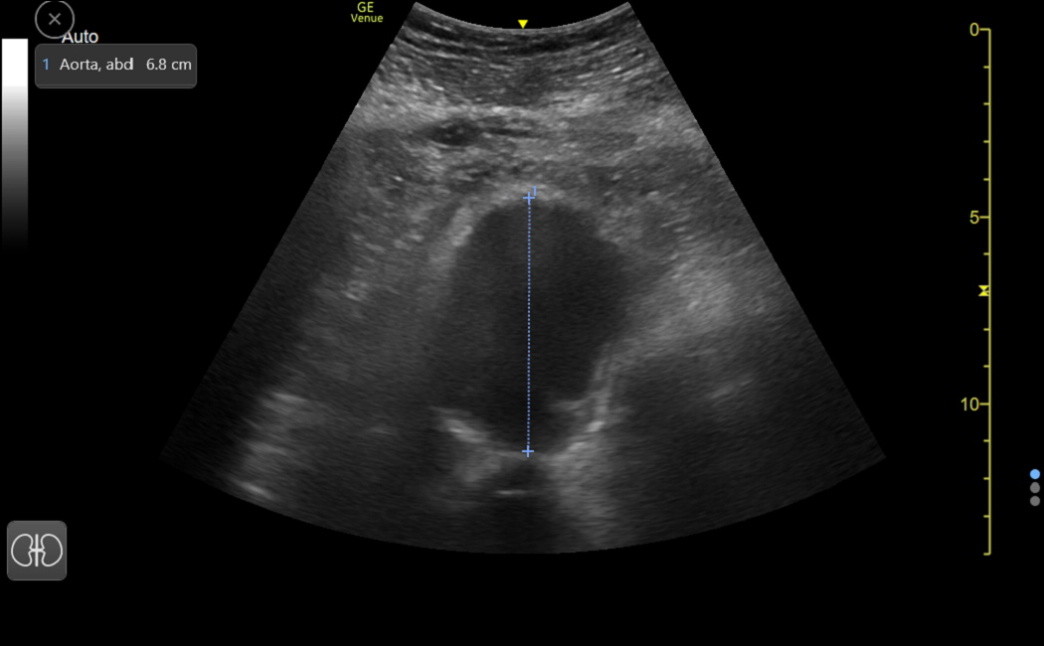

The following image shows a correct measurement of the AAA past the thrombus.

The last image is a large AAA from an older woman in our clinic. The anterior caliper should have been placed a few tenths higher, but this didn’t affect the urgency with which she needed vascular surgery consultation. This was found during a Medicare Wellness visit when a palpable abdominal mass was noted.